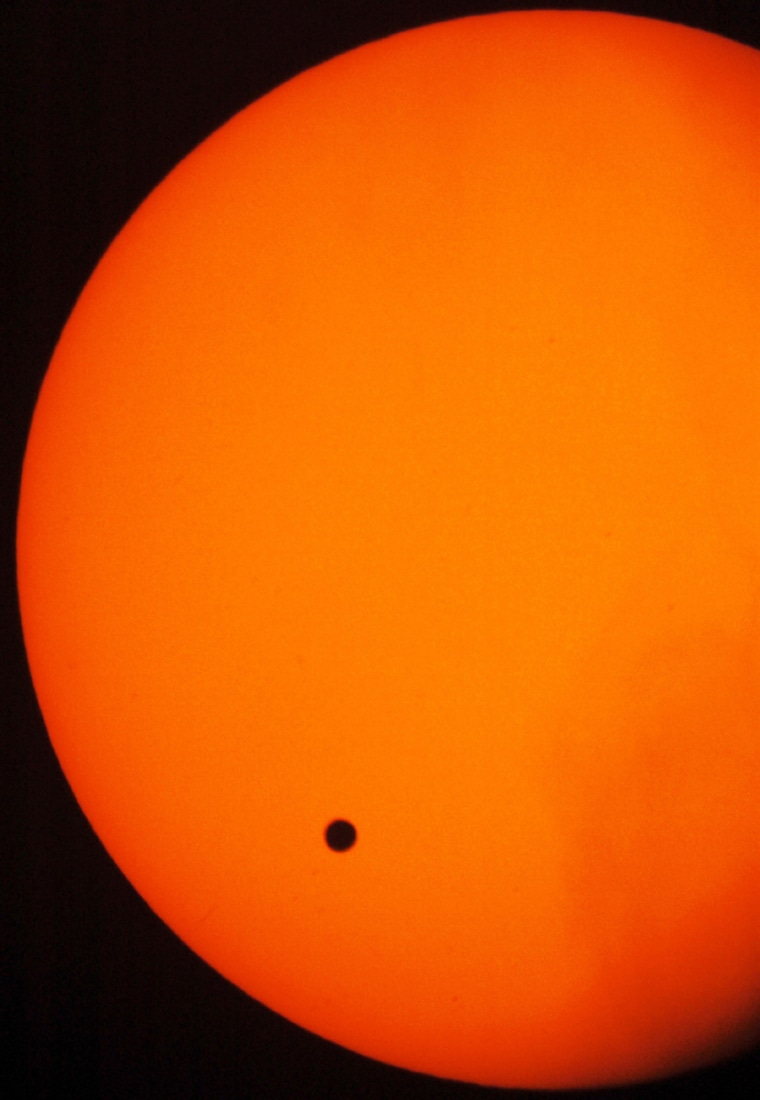

In this old center of stargazing, as in much of the world, thousands watched a rare heavenly show Tuesday: the black dot of Venus inching across the blazing face of the sun.

“Ecco!” gasped one matronly woman as the big screen at Piazza VIII Agosto showed a tiny perfect circle edge into view. “There it is!”

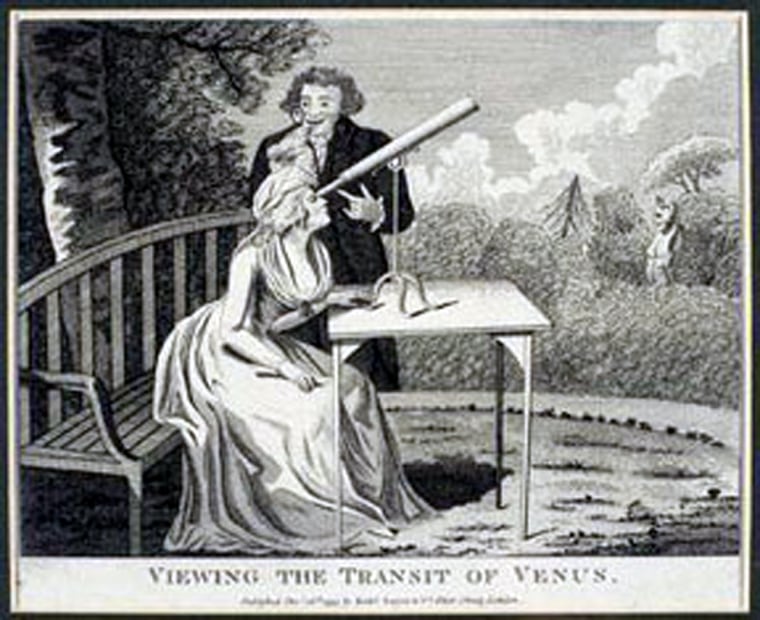

When scientists first worked out Earth’s distance from the sun, the Venus eclipse was crucial. “This sight is by far the noblest astronomy offers,” Edmond Halley, of comet fame, declared in 1691.

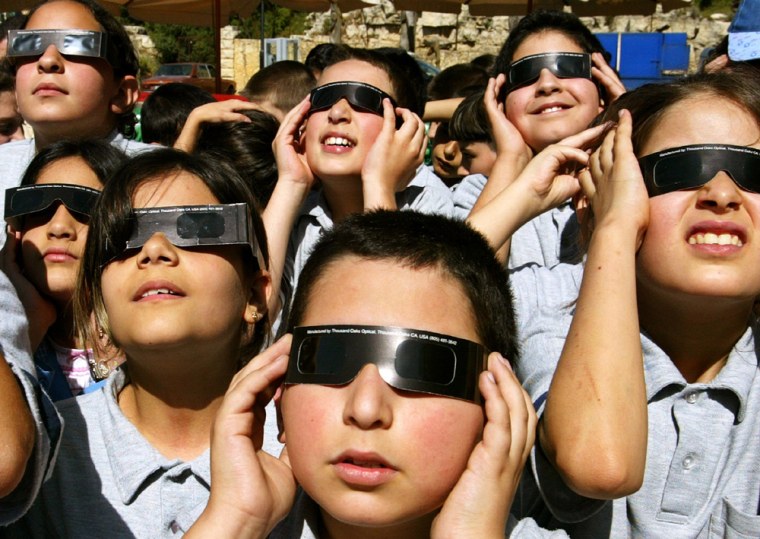

Now mostly a curiosity, the celestial rarity still had excited crowds lining up to peer into telescopes from Australia to the American Midwest.

“It’s a brilliant opportunity to know the mechanics of our solar system,” said 14-year-old Shereeza Feilden at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England.

“Spectacles such as this reinforce my belief that there is a Creator, and we are just tiny specks within this universe,” Zulkarnain Hassan, 26, said in Malaysia, a mostly Muslim nation.

Reactions were similar from people who shared a faith-straddling religious experience to those who marveled at a universal phenomenon.

“Imagine,” said Bologna astronomer Corrado Bartolini. “We can’t even tell when a car will reach Zamboni Gate in traffic, but we know to a fraction of a second when Venus meets the sun every 122 years.”

Venus makes two passes across the sun, eight years apart, every 122 years; the next one will be in 2012. As the sun is 30 times bigger, the planet is barely visible through special dark glasses.

'Man and woman and love'

Nicolo Reale, an art student in wild dreadlocks, forgave his roommate for dragging him out of bed to see Venus at the piazza. “Stupendous,” he said. “It makes me think of man and woman and love.”

In Oslo, Norwegian astronomer Knut Joergen Roed Oedegaard proposed to Anne Mette Sannes on a viewing platform, and the 2,000 people who gathered there thundered their applause when she said yes.

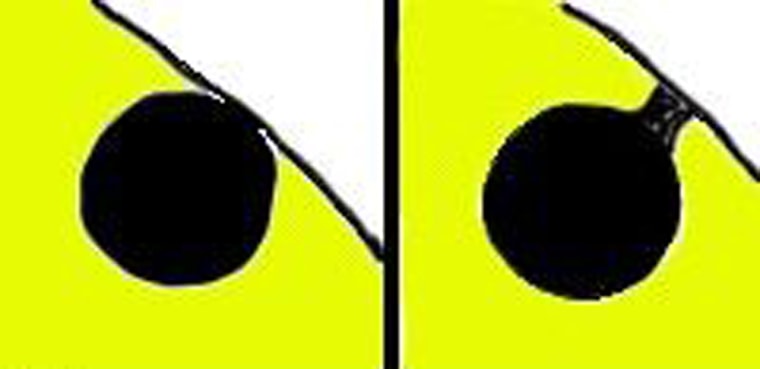

American experts worked at opposite ends of Greece — on the island of Crete and at Thessaloniki — to study the “black drop effect,” which shapes Venus into a teardrop as it approaches and leaves the sun.

“It’s like a fine French wine for the people who know about it and enjoy it,” said Jay Pasachoff of Williams College in Massachusetts, who watched from Thessaloniki’s Aristotle University.

The eclipse seemed to have a particular significance in northern Italy, where astronomy took shape in the Middle Ages.

“Think of what this meant to people who spent their lives trying to solve these ancient mysteries,” said Flavio Fusi Pecci, director of the observatory at the 900-year-old University of Bologna.

Dante Alighieri studied the stars here in 1287, and Nicolaus Copernicus, a Pole who came to Bologna in 1497, refuted Ptolemy’s ancient belief that the sun did not move.

Then Galileo Galilei, in nearby Florence, devised a telescope to reduce the guesswork.

The German Johannes Kepler calculated Venus’ path, although he died a year before the 1631 transit.

Public fascination

In cities from Sydney to New York, observatories set up telescopes to give the public a closer look.

Sixteen 4-year-olds from Elisabetta Simonella’s Bologna kindergarten class appeared puzzled at all the fuss over a black speck on a big orange circle.

But Teodoro Bernardino, a Spanish scientist, knew what he was seeing.

These days, he said, scientists have taken astronomy into deep space, and monumental puzzles are solved out of sight. “But it is important to build the public’s interest, to share the fascination.”

Worldwide collaboration

The last Venus transits visible in Europe, in 1761 and 1769, brought what Fusi Pecci calls the first worldwide scientific collaboration in history.

“In all, 1,000 people from 100 observatories worked to solve this mystery — how far the sun is from the earth,” he said. “And this in spite of a seven-year war going on between France and England.”

Knowing the distance from Earth to the sun was vital to calculating size within the solar system.

Copernicus surmised the distance at less than 6 million miles. Kepler upped the figure to nearly 15 million. In fact, space exploration has found, 92,955,859 miles (149,598,253 kilometers) is closer to it.

Viewing from the Americas

Rising before dawn in Argentina’s bone-chilling autumn cold, 200 people in Buenos Aires shivered while they took quick turns on six outdoor telescopes trying to get a peek at Venus.

In the United States where only people in the eastern half of the country could catch a glimpse at sunrise, about 300 New Yorkers showed up to look through a bank of telescopes in Central Park.

About 500 people lined up before sunrise to at the rooftop telescopes at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.

“The marvel, the wonder of it,” said Clydia Davenport of Boston, who brought her 7-year-old daughter, Sophie. “It’s interesting also that it’s Venus. A beautiful woman is doing this, and we’re all out here to watch, like voyeurs.”

Some cities celebrated by playing American composer John Philip Sousa’s “Transit of Venus March,” composed after the 1882 transit.

Food for thought

However, not everyone caught Venus fever.

“The what?” said Bologna delicatessen owner Romano Bonaga when asked about the event. “I’m afraid now we think more about materialistic things. And food.”

But at a meeting of the Bologna Amateur Astronomers Association, computer programmer Andrea Berselli had a different view.

“I’m interested because this is such a rare phenomenon that says so much about who we are,” he said. “My parents never got to see it. My kids won’t get to see it. That has to mean something.”