By the time the boy was 5, the hole in his heart had grown large enough to require surgery. Doctors would make a cut in the shape of a giant Y in his chest, then hook him to a machine that would keep blood flowing while they reached in and stopped the beating heart. Only then, with the heart limp and lifeless, could they patch the hole with a mesh-like substance that was supposed to keep it from malfunctioning for the rest of his life.

And on the day Brian Roberts was to have his heart turned off, the anesthesiologist misjudged the time needed for his drugs to take effect. The boy was awake and appropriately terrified when they came to take him to his operation. They picked him up anyway and, in a moment his parents still recollect with agony, the boy buried his fingers in his mother's neck, begging her to keep them from taking him.

"Mommy, I don't want to go!" he shrieked.

But the mother stayed firm. It was the father, a baseball coach, his skin toughened into a leathery hide, who watched his boy howl and felt himself go. The doors opened, his son disappeared and right there in the hospital, before everybody, the old coach began to cry.

Hearts can be funny things, though. You can't always judge them by their wounds. Sometimes the most damaged of them can grow to be the strongest. Sometimes, too, the determination of those fragile hearts can make the toughest men go soft.

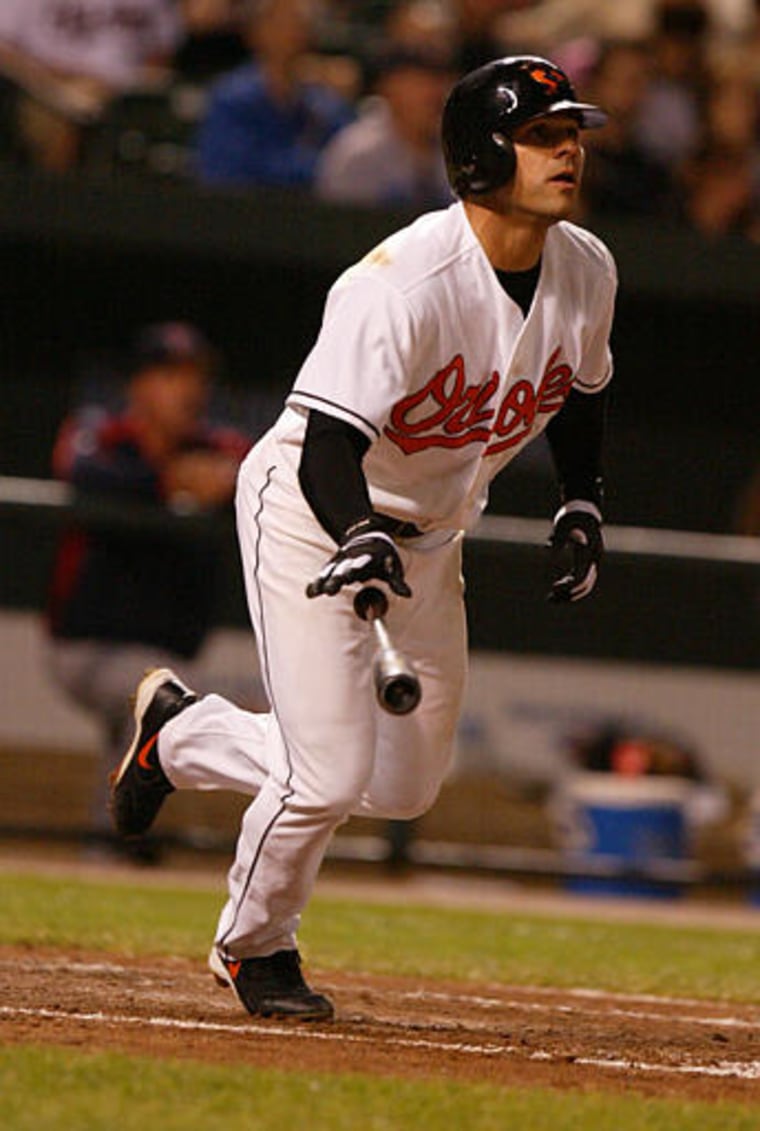

Nobody gave Mike Roberts's son much of a chance at sports. Brian Roberts never did get to be very big. The Baltimore Orioles say their second baseman, in the top five of just about every hitting category this season, is only 5 feet 9. Even he says he is just 5-8 and about 170 pounds. Standing next to the rest of his teammates, he looks like he might not even be 5-5.

This got him overlooked in the game he loved the most. He was short, with stringy arms and small legs. He did not seem like an athlete. When he walked onto the field for batting practice, he did not hit the ball far into the trees the way the bigger players did. He was, in a sense, the kid down the street who adored the game his father coached so much that he wouldn't stop coming around.

So the father molded him in a way not many players were being made anymore. If the boy couldn't hit the ball into the trees, then he would become something else — a player so fundamentally perfect, fast and with quick hands that he would be impossible to ignore. Not that everybody noticed.

Whenever he'd make a team or earn a starting spot, the whispers soon followed.

"You only got this because your father is a college baseball coach," people said.

Mike Roberts cringed when he heard this because he saw something that nobody else did. Maybe this is the father in him. Maybe it's the coach.

"I think everybody judges a player today by how far the ball jumps off the bat," he said. "Mike hit ground balls but he would always ground the ball off the meat of the bat. I think a lot of people overlooked his fundamentals."

Strengthening his game

Every night they played a game on Highview Street outside their home in Chapel Hill, N.C., where Mike was the coach at North Carolina. Mike would mark off a distance, from a mailbox to a manhole cover and have Brian throw. Then he would stretch that distance, longer and longer until they were going from one mailbox to another way down the street and then to a manhole cover even farther away.

Eventually, when he thought his son was ready, Mike took Brian to the field at North Carolina and had him stand at home plate. Mike ran down the left field line and again they stretched out their throws until eventually Brian could heave the ball over the fence 336 feet away.

"People ask me if I'm proud of him," Mike Roberts said. "That's not what I would say. I'm happy for Brian because it's so important for young people to dedicate themselves if they have a dream and I think Brian is fortunate to be living his dream."

When high school was over there were no scholarships for the kid who could outrun and out-throw everybody. Once again, the only person who believed was Mike Roberts, who brought his son onto his team. And there Brian Roberts thrived, being named the nation's college freshman of the year in 1997. But when Mike Roberts left the school in a dispute during Brian's junior season, the new coaches did not want the boy molded in his father's image. So once again rejected, the son went to South Carolina, where he hit .353 and led the nation with 67 stolen bases.

And yet that was only good enough to be picked 50th overall by the Orioles.

No, it was not easy. His mother, Nancy, searching for a word to describe her son's drive, finally hits on one.

"Perseverance."

"He just knew this is what he wanted to do," she said one day recently by phone from North Carolina. "He didn't enjoy academics in school and if he didn't want a real job and have to go to work every day, he knew what he had to do."

The little heart, mended one day on a doctor's table, beat harder. It pushed faster.

"You know if he was 6-foot-1 he would have been the first pick in that draft," said Royals pitcher Kyle Snyder, who was Brian's roommate at North Carolina. "That's where he gets his drive and where he gets his fire. The kid's got character, man. You can't judge that in a scouting service."

But ask Brian Roberts, now hitting .382 and who entering last night was first in the league in hits, first in runs, fifth in home runs and second in stolen bases, what it is like to finally be on top of the world, to have everything go right, and he smiles then gives a small shrug.

"It's a lot better than when it's not going right," he said.

His father said Brian gets this from his mother — the self-deprecating laugh, this blase scoff at the success he has longed to have his whole life. Nancy Roberts could always control her emotions the way Mike Roberts never did. And now here's their son, probably the best player in baseball to this point this year, and all he can do to acknowledge his dominance is shrug and make a weak joke.

But the fact is there is a difference. Brian can see it, taste it, feel it every time he steps out of the dugout. He believes. He knows he's good. No longer does he need his father to tell him, he knows it all too well himself.

Relaxed and ready

Everything slows down when you are on fire the way Brian Roberts has been this year. The pitches that roar in at 95 mph look about 70, the curves don't break, the game suddenly seems so simple. This is an old trick the mind plays on players who are going well. For the first few years of Roberts's career everything seemed to fly at him too fast to corral. Then all of a sudden this season came and the racing stopped.

The other day he stood in front of his locker, holding a bat, and tried to explain this sensation.

"You're concentration level is that much bigger, I guess," he said. "When you're struggling, everything's like 100 mph. You try to run out to the plate so you can go out there and accomplish something. Then this year it wasn't like I went up there on my first at-bat and said 'Here we go.' It's gradual and having some success makes it easier whenever you go up there. Being confident in yourself and being relaxed, that's the key.

"The biggest thing in this game is you can't fear failure."

Everything changed for him the day the Orioles traded Jerry Hairston for Sammy Sosa. This opened up second base full time for Roberts, letting him play every day rather than leaving him to wonder when he was going to be in the game. Eliminating the platoon also eliminated a host of insecurities that haunted him through his time with the Orioles. Could he play? Was he really good enough? It was hard to have to check a lineup card every afternoon to see "if you or myself was looking over your shoulder every time think how hard it would be?" Roberts said. "You start thinking 'If I go 0 for 2 I better get two hits or it's over.' You can't play this game that way. When you have 700 at-bats you're going to go up and down."

Baltimore broadcaster Buck Martinez, a former major league manager, has a theory that big league hitters don't really become comfortable until after 1,500 at-bats, which is just about where Roberts began the season (1,502). Making the adjustment harder is the fact that Roberts, a switch hitter, didn't always work both sides of the plate before games. Martinez, who often watches batting practice from the back of the cage along with hitting coach Terry Crowley, noticed that in the past Roberts would only hit from the side he was going to use against that night's starter. This left him unprepared to face a reliever who threw with the opposite arm and kept him from fully developing both swings.

Now Roberts hits from both sides in batting practice.

To watch Roberts in the cage is to wonder how a player with no more than five home runs in a season in the majors or minors could possibly be on a pace to hit close to 50 home runs this year. He is so small and he doesn't stand there like the sluggers ripping away at the bleachers. He hardly takes a swing at all, slapping the ball to left, trying to pull another one between second and first.

This is the dichotomy of the Orioles' leadoff hitter. He is leading off because he gets on base like nobody else in the American League. But instead of falling for singles and doubles as they did in the past, his hits are going over the wall.

His father thinks it's a result of Brian's offseason conditioning workouts in Tempe, Ariz., a training regimen that has taken the lean body and sculpted it with more muscle tone. After years of being the smallest player who had to outmaneuver the other kids with savvy and guile, Roberts has blossomed into something bigger, stronger. And as a result his fly balls have become home runs.

"He's continued to hit the ball squarely and the ball's jumped," the elder Roberts said before quickly reminding a caller on his cell phone that his son is still a leadoff hitter and not necessarily required to hit balls out of the park. "I don't think it would bother him if he never hit another home run this year," Mike Roberts added.

The strange part is that this player, who has worked so hard to get here and is tearing apart the American League, could walk away tomorrow. He said this almost casually as if it is the kind of thing a 27-year-old ballplayer with his future finally in his grasp would normally say.

Outside interests

The subject is religion. It's not one you can touch lightly. Church was always a part of his life, from the twice-weekly services to the trips to the Fellowship of Christian Athletes events. His faith was reaffirmed his freshman year at North Carolina when a dreadful fall on the baseball team and academic struggles prompted his mother to send him a book by the basketball player A.C. Green, who famously claimed he remained a virgin for religious reasons until he was married. She said she has heard her son say the book changed his life -- so much so that she wonders if he will someday go into the ministry.

"For me baseball's not the end-all, be-all," Brian Roberts said. "If I'm not in this game this year or next year or the end of next year, it's not the end of the world. Don't get me wrong. I love the game of baseball. I just believe there is more to life."

Recently he visited a hospital not far from Oriole Park at Camden Yards. It was a place he has visited many times, usually without much attention. After all, who would recognize a 5-8, 170-pound second baseman? For that matter, who would much care?

This time it was different. This time the children knew him, they had questions, they wanted to hear the suddenly famous ballplayer speak. This amazed him because this was a hospital, after all, and many of the children were very sick. And yet they knew everything, the stats, the numbers, the fact he was the hottest hitter in the American League.

Something like this had never happened before. In a way it seemed to perplex him.

"I don't feel like I'm much more different than anybody else," he said. "I mean, look at Melvin Mora or whatever player. Melvin played in other leagues, then he has six kids and his brother got shot. I've been through a lot, but so has everyone else."

Nancy Roberts said the reason her son likes going to hospitals is because he thinks he can relate to the children lying in the beds. That he can tell them about the day the doctors cut a Y in his chest and the anesthesia didn't kick in and he was pulled into the operating room still clinging to his mother's neck. It also helps that he is someone who is roughly the same size as many of the children he is visiting. Perhaps on some level they see him differently, someone in whom they can see hope.

At night, when father and son talk by phone, the conversation is not about baseball. "He's not like me," said Mike Roberts, who now coaches a team in the Cape Cod summer league. "When I coached in college, I could talk baseball 24 hours a day. I've rarely heard Brian sit down and discuss other players and the game. I think he surrounds himself with people outside the game."

The irony, of course, is that it is the game he owns right now, the game he fought so hard to be a part of and the game that suddenly seems easy. It's just that he seems uncomfortable making himself seem more special because of the path he took to get here.

But it is his story and it is different from so many of his teammates for whom the game came easy.

"Brian is a backyard player, a Wiffle ball player," Mike Roberts said. "In Wiffle ball, power is not part of the game. In Wiffle ball, you have to have imagination. You have to be a player that is pitching and then has to go play first base. Whether Brian was in the backyard or the beach, he used to play pickle all day long. We used to call it rundown.

"If you saw him as a kid at games in Chapel Hill, he was always playing rundown on a hill above the field. He was not your prototypical player who could just hit the ball far."

Ultimately, the flawed heart has grown until it has pushed the littlest player past all the bigger ones, past all the people who said he wasn't a ballplayer, that the only reason he was on a team was because of his father's connections.

And in this Orioles season that has come from nowhere, it might be the most amazing story of all.