WASHINGTON — There was a time when the regions of the U.S. were clearly defined and understood entities: the Middle Atlantic, the Southeast and the Midwest. But the lines have blurred, and a quick look at demographics (and election results) will tell you Chicago and Atlanta have more in common with each other than the rural parts of their respective states.

Regional trends and viewpoints are increasingly being replaced by national ones that cross state and regional boundaries in the worlds of business and politics. And as fall arrives, you can see that shift affecting even the world of college sports — particularly college football.

Ad revenues and audience models are dramatically reshaping the world of college athletics, destroying what were once regional conferences. The changes have been evolving over decades, but this football season is a watershed. It will mark the end of what was once known as the “Power Five” conferences and create what amounts to four large national college football divisions.

A look at the remaking of the Power Five conferences over the last 40 years shows the changes clearly.

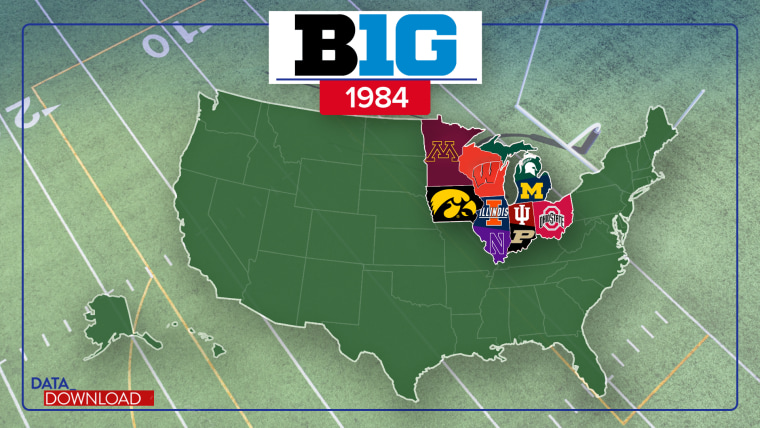

Let’s start with the Big Ten, which created a stir this summer when it announced it was going to grow again — to 18 teams.

Back in 1984, it was essentially a football conference for the country’s Great Lakes region, going no farther east than Ohio and stretching into Iowa.

Flash-forward to 2024, and the conference will look very different.

It’s not just that the Big Ten will have 18 teams, having had more than 10 teams for 30 years. Just look at the conference’s footprint for 2024. It will stretch to Maryland and New Jersey in the East and California, Oregon and Washington in the West, capturing TV markets and fan bases across the country.

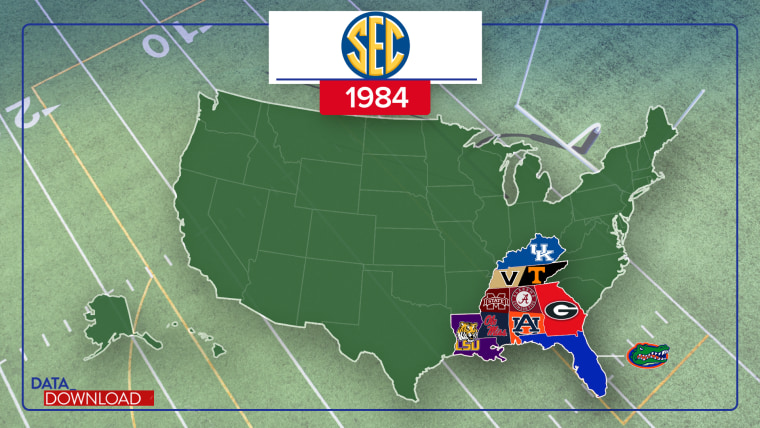

The Southeastern Conference has made smaller moves in that time, but it has definitely moved out of the “Southeast.”

In 1984, the conference was home to just 10 teams in seven states: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee.

Next year, the SEC will house 16 teams in those seven states, in addition to schools in Arkansas, Missouri and South Carolina, along with Oklahoma and Texas.

To be fair, all the states with schools in the new conference will be contiguous, but the footprint is noticeably bigger, adding millions of fans along the way.

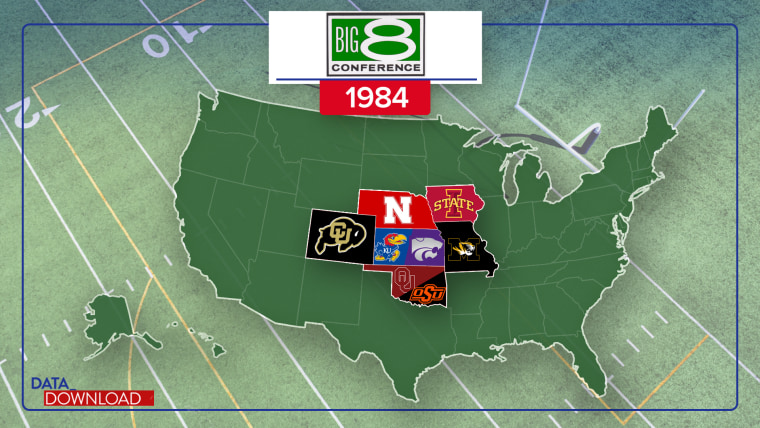

The changes to what was known back in 1984 as the Big 8 are massive.

Forty years ago, the conference was home to schools in a small set of states in the middle of the country, from Iowa and Missouri in the east to Colorado out west.

Next year, the Big 12 (as it is now known) will be home to 18 schools in 10 states — and only five of the original schools, including Colorado, which is coming back from the Pac-12.

It will stretch from West Virginia in the East to Utah and Arizona in the West. Like the Big Ten, it is a patchwork of states scattered across the country without any kind of regional identity.

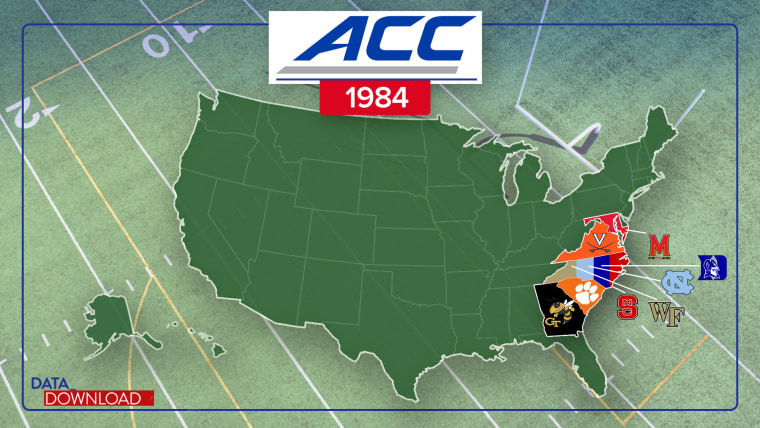

But when you get beyond the numbers, the Atlantic Coast Conference may have the name that’s hardest to defend in 2024.

Back in 1984, the ACC was truly a tight regional conference: eight schools in just five states, all connected down the East Coast, from Maryland to Georgia.

The new ACC will grow to 17 teams (in football) with schools covering the country, from New York to Florida to Texas and California.

It’s jokingly been labeled the All Coasts Conference.

But the biggest change in college football in 2024 will come in what once was the Pac-10.

Forty years ago, the conference was a collection of 10 teams in four contiguous states running down the west side of the country — Washington, Oregon, California and Arizona.

Next year it will cease to exist, with most of its members going to the new national conferences.

Four of the 1984 members are going to the Big Ten, two are going to the Big 12, and two are going to the ACC. The others, Washington State and Oregon State, don’t yet have homes.

You can look at these changes and say: “Well, it’s just football. What difference does it make?”

But in the broader sense, sports and our relationship with them are always in some way about the larger culture. And the changes are about a much bigger shift that has remade the country in recent decades.

We may still talk about regional differences, the dialects and cuisines that give places unique feels and flavors. But the changes in college football look a lot like the changes in business and politics and media in the country. They are more evidence that a national culture has emerged in the U.S. — running from Saturdays in the fall through to Tuesdays in November.