WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court’s decision last month putting an end to the use of affirmative action in higher education admissions paved the way for potentially dramatic changes in who gets into college and where they go.

The case revolved around affirmative action policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina, but the impacts will touch campuses across the country — at least campuses that receive federal funding. And while the extent of the ruling will become clear only over time, even a cursory look at the data around educational attainment shows two very important points hold true.

First, sharp racial and ethnic divides remain around who has bachelor’s degree in the U.S. And second, those differences have very real socioeconomic impacts in broader American society.

Over the past 60-plus years, the number of people who get bachelor’s degrees has grown across the board, but some consistent racial and ethnic disparities remain.

Since 1960, the percentage of people over age 24 with a bachelor’s degree has climbed by more than 27 percentage points, from 7.7% in 1960 to 35% in 2021, according to the census.

White non-Hispanic U.S. residents have had a slightly bigger jump in degrees, a 29-point increase, from 8.1% in 1960 to more than 37% in 2021. And Asian residents have had a massive 44-point increase in degrees in that time, climbing to almost 56% in 2021.

But among Black and Hispanic U.S. residents, the increases, while still substantial, have been smaller. Since 1960, Black people’s bachelor’s-or-more population has climbed about 20 percentage points, from 3.5% to 23.3%. And currently, 18.4% of Hispanics have bachelor’s degrees. The census didn’t tally numbers for that population in 1960, but since 1970, it has climbed by about 14 percentage points.

The smaller increases aren’t a complete surprise. College degrees tend to beget more college degrees. If parents go to college, their children are more likely to wind up on campus. And over time, the college degree numbers for Blacks and Hispanics could accelerate as those impacts work through those racial and ethnic groups.

The gaps are still very wide, however. And other data show how meaningful they are.

Getting a college degree is about a lot more than getting a piece of paper to hang on one’s wall. A college education tends to increase people’s earning potential —and to protect them during economic downturns.

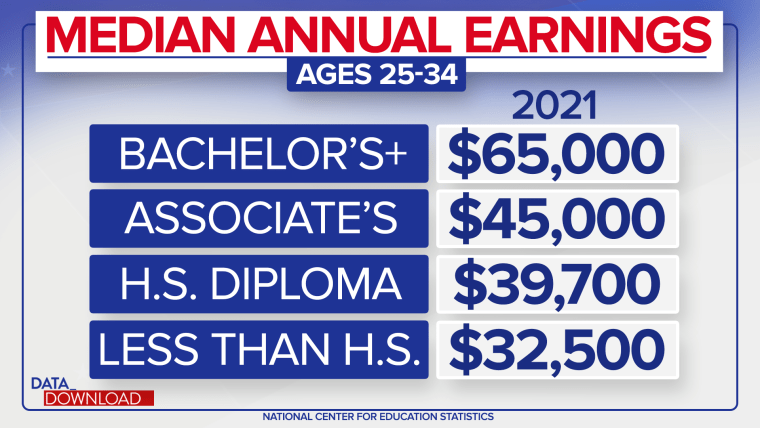

In terms of income, a bachelor’s degree can be worth tens of thousands of dollars annually, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

The median annual earnings for a 25- to 34-year-old with a bachelor’s degree or more was $65,000, according to the NCES. The figure for those whose highest level of educational attainment is a bachelor’s degree alone was $61,600.

The numbers drop sharply after that. For those who topped out with an associate (two-year) degree, the median figure is $45,000. For those, who stopped going to school after the 12th grade, the figure is $39,700. And for those without high school diplomas, the median figure is $32,500.

To be clear, those figures are medians. There are plenty of people without bachelor’s degrees who make more than the median and plenty with bachelor’s degrees who make less, but the people in the middle show just how much a degree can be worth. Even if a college degree is costly, the data suggest it can pay for itself pretty quickly.

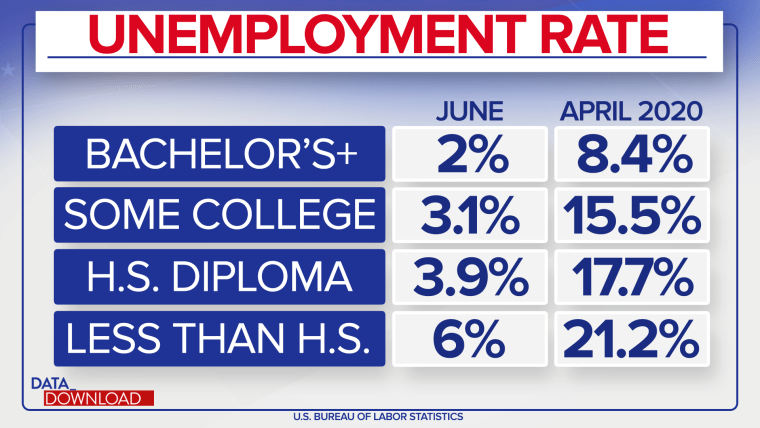

Furthermore, the data indicate those who have four-year degrees are more likely to have jobs in the first place and more likely to hold on to their jobs when the economy dips.

In June, the unemployment rate for those with bachelor’s degrees or more was 2%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For those with some college or associate degrees, it was 3.1%. For those with no college but high school diplomas, it was 3.9%, and those without diplomas had an unemployment rate of 6%.

Those are real differences, but all the figures are low right now because there are a lot of jobs available in the economy. Back when the pandemic hit in April 2020, the differences were massive — with a huge advantage for those with bachelor’s degrees. People with four-year degrees had an unemployment rate of 8.4%. But all the other groups were in double-digit terrain: 15.5%, 17.7% and 21.2%, respectively.

In other words, a college degree still looks like a ticket to the middle class, broadly speaking.

And because of existing economic disparities between the nation’s different racial and economic groups, Black and Hispanic people face another challenge where college is concerned: cost.

College isn’t cheap, and it’s gotten much more expensive in recent years. That has placed an especially big economic burden on Black people who want to pursue higher education.

Black men ages 20 to 35 are more likely to have student debt than their white and Hispanic counterparts — 44% versus 41% and 35%, respectively, according to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve. Black women in that age group carry the most student loan debt by far, $11,000 on average, and they are much more likely to have student debt. More than half of Black women in that age group, 53%, have some student debt, compared to 46% for white women and 39% for Hispanic women.

In some ways, even those numbers mask the student debt Black and Hispanic college graduates are carrying. The figures are averages for every 20- to 35-year-old in the country — and because fewer Black and Hispanic people have attended college, the debt averages among only those who did attend are higher.

It all serves as a reminder that with or without affirmative action, the challenges in creating equal opportunities around college education in the U.S. are complicated. And the socioeconomic stakes are high.