WASHINGTON — In the past few election cycles, color-coded result maps have developed a very familiar pattern at the county level. They mostly look like seas of Republican red punctuated by small islands of Democratic blue, even in races that end up being close.

The maps are a sign of a major remaking of U.S. politics over the past few decades, a remarkable deepening of the nation’s political urban/rural divide. And for some Democrats, there are questions about whether the split is getting too wide.

There is a long list of reasons Democratic candidates do better in cities. The party tends to do better with nonwhite voters, who usually make up larger parts of urban environments. The party also tends to win larger percentages of younger voters and voters with bachelor’s degrees, and they also tend to live in and around cities. And, generally speaking, urban areas tend to be more culturally and socially liberal.

But the size of the rural vote shift in the last few decades, in particular, has been astonishing.

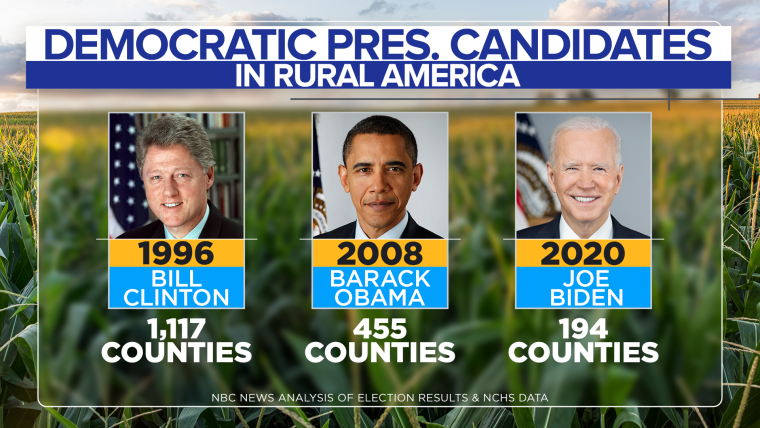

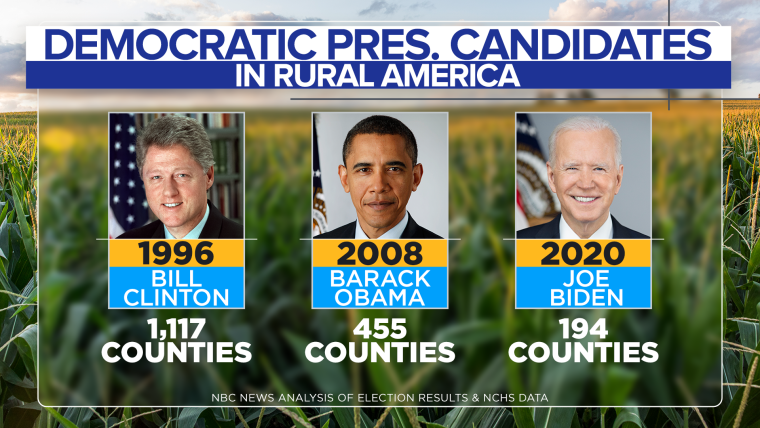

Back in 1996, then-President Bill Clinton won about 1,100 rural counties. (The analysis, which is based on the National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme, counts the two least populous groups as “rural.”)

Clinton had some advantages in speaking to rural voters. He came from Arkansas, a state with a lot of rural areas, and maps from that election, even outside the South, show he won substantial rural territory. For example, Clinton won all but 20 of Iowa’s 99 counties and did fairly well in the more rural western half of the state.

To be fair, some of Clinton’s rural edge may have been due to his landslide 10-plus-point popular vote margin, but consider the change in Barack Obama’s win in 2008. Obama also won the presidency by a sizable margin, more than 7 points in the popular vote, but he won only 455 rural counties. That’s only about 40 percent of the rural counties Clinton won in 1996.

Flash forward to 2020 and President Joe Biden’s win, and the number shrinks to fewer than 200 rural counties won for the Democrat (about 17 percent of Clinton’s 1996 rural total). Granted that the race was closer and Biden won the popular vote by about 4.5 points, but a diminution of the Democratic vote is hard to ignore. Even in Michigan, a state he carried, Biden won only 11 of 83 counties.

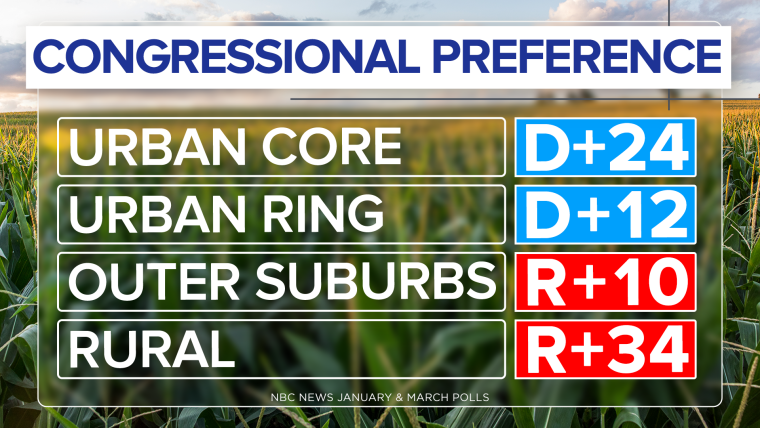

And the problem for Democrats hasn’t gone away since Biden’s election, according to a merge of data from the January and March NBC News polls, which use a different system to categorize urban, suburban and rural voters.

In deeply urban areas, there is a strong preference for Democratic control of Congress by a margin of about 24 points. And in dense suburban areas, the party still holds a sizable 12-point edge. But then things turn. In outer suburbs, Republicans are the choice by about 10 points. And in rural areas, the Republican edge grows to more than 30 points.

For the most part, Democrats like their urban advantage, and for good reason. Oftentimes, that sea of red with a few blue islands is enough to win. Elections aren’t won by acreage; they’re won by votes, and those blue islands hold a lot of votes.

But there are challenges, as well.

For instance, if the GOP’s red tide gets to be too big, those islands may shrink too small to save the Democrats. In 2020, Biden won Pennsylvania by a little more than 1 point, and he won Wisconsin by less than 1. In those states, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Madison and Milwaukee saved the day for Democrats, but barely.

And beyond that, in some states there just aren’t enough blue islands to help Democrats. Wyoming and Nebraska each had two blue islands in the 2020 presidential race. West Virginia and Oklahoma had none. Those states send eight senators to Washington, and currently, seven of them are Republicans.

Add it all up and the challenges in the urban/rural divide for Democrats become clear, particularly as they try to wield power in Washington. Some of the split is a function of true party differences over policy and demographics. But if the Democratic Party goes too far down the road to become the party of just urban America, a true functional working majority looks very difficult to achieve.