While heroes fall out of the spotlight for a number of reasons, Bayard Rustin, the civil rights leader who organized the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, never fully emerged from the shadows. During his lifetime, “Mr. March on Washington,” as he was nicknamed by labor titan A. Philip Randolph, advised some of the country’s most influential thinkers on nonviolence and the power of mass protest. But this year, which marks the 60th anniversary of the march, is the first in recent memory that the work of the openly gay activist, who died in 1987, has captured the popular imagination of the American public.

“At the time that he died, he had sort of fallen out of the headlines. I wouldn’t say he was obscure; he was certainly known to the movements that he worked on, but not so much the general public. And then, suddenly, this kind of magical moment has appeared,” Walter Naegle, Rustin’s former partner and a contributor to a new essay collection on his legacy, said of the new book and a film debuting this year.

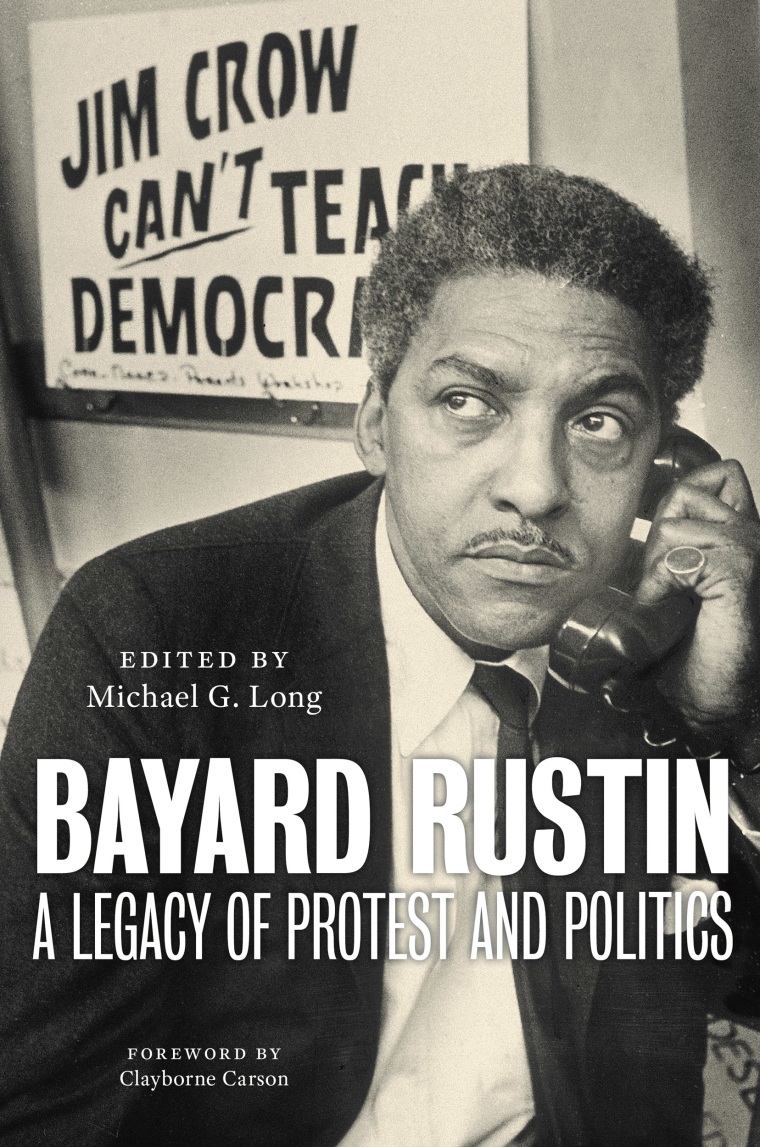

The collection, “Bayard Rustin: A Legacy of Protest and Politics,” features 19 essays that explore the highs and lows of the activist’s life and career and his impact on American society in the past century. Edited by Michael G. Long, the new book is part of a wave of analysis that’s emerged in anticipation of the march’s 60th anniversary and the release of “Rustin,” a buzzy Netflix biopic starring Coleman Domingo, releasing in November.

“Books can be released into a vacuum or they can be released into a perfect storm. It’s really a perfect storm for releasing this book,” Long said, referring to the year’s notable Rustin-related events, as well as decades of scholarship that form the “building blocks” for the collection.

In addition to his works on figures like Jackie Robinson, Martin Luther King Jr. and Phyllis Fry, Long has edited and authored several others on Rustin. (One of them, “Troublemaker for Justice: The Story of Bayard Rustin, the Man Behind the March on Washington,” was co-authored with Naegle.) But, he said, with the recent collection his aim was to “step back and assess” Rustin’s legacy, rather than just describe it.

To that end, Long brought together an array of academics, activists and authors whose essays touch on how Rustin’s upbringing and identity shaped him, as well as how he, in turn, shaped generations of protest movements in the U.S.

“Yes, he was ‘Mr. March on Washington,’ and it makes perfect sense to celebrate that. But it’s also important for us to celebrate and criticize and consider his work in all these other fields as well — from gay rights to his anti-war campaigns to his anti-nuclear campaigns to his work for refugees,” Long said. “Looking at Rustin’s work is a way for us to explore the major social movements of the 20th century.”

Rustin, who was raised in West Chester, Pennsylvania, by his Quaker grandparents, began his professional career as an activist in the early 1940s. Early on, he served as an organizer for influential racial justice and anti-war campaigns — work that was interrupted by his imprisonment as a conscientious objector from 1944 to 1946. As his reputation grew, he fought for a place among the leaders of the modern civil rights movement that emerged out of World War II. And while he had supporters in figures like civil rights activist Ella Baker and Randolph, who shared his belief in the power of mass demonstration, he had detractors in various wings of the movement, including the influential NAACP leader Roy Wilkins. And his sexuality, as well as his early involvement in the Young Communist League, made him an easy target for slander and blackmail.

Although the crowning achievements of his career were organizing the Aug. 28, 1963, March on Washington and schooling Martin Luther King Jr. in the principles of nonviolence, his interests and influence extended beyond racial equality, as he spent decades protesting American war efforts, nuclear expansion, the treatment of political refugees and economic inequality.

“These problems are still with us. In terms of race relations, we’ve made a lot of progress, but in terms of economic inequality, the gap between the rich and the poor, it’s only grown. And until we really confront those issues in this country, we’re not going to make tremendous progress,” Naegle said, referring to the collection’s place in the current social discourse. “It’s not just ancient history, if you will.”

While the approximately 200-page collection undoubtedly celebrates Rustin’s visionary approach and his influence on American protest culture — which can be seen, as Long points out, in recent movements like Black Lives Matter — it also attempts to turn a critical eye to his policies and career progression.

Following the March on Washington, for example, Rustin advocated for a turn from “protest to politics” and urged the major civil rights organizations to align with Democratic Party allies, a strategy that many saw as detrimental to the movement. As part of his new passion for coalition building and his budding relationship with the Johnson administration, the lifelong pacifist also “became reluctant to speak out against the Vietnam War,” as one essayist describes. And, as Long points out in his introduction, although Rustin was openly gay, “it would take almost two decades after the Stonewall Uprising before he would become a visible activist in the movement.”

Speaking to the importance of the collection’s comprehensive approach, Naegle — whose essay is entitled “The Legacy of Grandmother Julia Rustin” — referred to the weight that Rustin placed on transparency and truth because of his defining relationship with the woman who raised him.

“Going back to his training and values, Quakerism really is about authenticity, openness, transparency and a search for the truth, which is something that we never really find in an absolute sense, but it’s an ideal that you reach for,” Naegle said of his deceased partner’s Quaker upbringing in Pennsylvania. “As Bayard himself would say, ‘You don’t get there, you don’t get to the truth without looking at all of the different pieces, all the different issues.’”

With the range of perspectives he brings together in the new book, Long does seem to get much closer to the truth of Rustin than some other recent depictions, which impart him with an almost saint-like quality. Though, the editor’s chief aim — making Rustin accessible and appealing to the masses in the way that he was during his lifetime — is perhaps slightly less lofty than the pursuit of absolute truth.

“We often put our heroes on pedestals, and we do that for good reason: They’ve done heroic things,” Long said. “Rustin certainly is a hero in the sense that he pushed our country in ways that it hadn’t been pushed before. He inspired millions of people, and he did it with dignity and grace. He also did it in the face of fierce opposition, especially from homophobes at the time.”

However, Long added, “The problem with putting our heroes on a pedestal is that they become unreachable. It’s important to look at somebody in their full humanity — not only their strengths but also their weaknesses, not only their incredible vision but also those blind spots.”

Blind spots and all, Rustin and his legacy have found a particularly enthusiastic audience more than three decades after his death, in an era when struggles for racial, social and economic justice have been reignited and a record number of anti-LGBTQ state bills have been introduced across the country.

“There’s been no community that has rallied around Rustin more so than the LGBTQ community,” Long said. “Here’s somebody who faced violent homophobia, homophobia that kept him in the shadows for many years. Here’s a man who overcame that to assume the podium at the March on Washington, during the largest nonviolent campaign in U.S. history up to that point — a man who strode out of the shadows of Lincoln and made demands of the U.S. government and society.”