Trying to explain why queer people love horror opens a haunted puzzle box of theories about otherness, sexual deviancy, subtext and camp, which is probably why it’s usually just accepted as gay gospel. But a new documentary series from the streaming service Shudder, “Queer for Fear,” sets the ambitious task of looking into the history of that unholy union, through conversations with creators, actors and personalities who have contributed to the genre’s recent body of work.

Among the talking heads, who float eerily in the foreground of the darkly lit interviews, are the creatives behind spooky films and series like “Sherlock,” “Russian Doll,” “Jennifer’s Body” and “The Craft”; the stars of “Child’s Play,” “What We Do in the Shadows” and “Yellowjackets”; and personalities like Michael Feinstein and the Mistress of the Dark herself, Elvira. Across the four episodes — which collectively comprise Shudder’s unofficial sequel to its 2019 documentary “Horror Noire,” about the history of Black horror — the LGBTQ entertainment experts chart the evolution of horror from 19th century literary works about monstrous intellectuals to the unsettling thrillers of Hays Code Hollywood.

“I’ve been watching horror for a queer perspective my entire life, starting with monster serials and ‘The Munsters,’ when it was family-friendly fair,” said Bryan Fuller, an executive producer of the docuseries and the creator of “Hannibal” and “Pushing Daisies.” “To have conversations with folks who have similar awarenesses but different interpretations has been really exciting, because we all have our own introduction to queer horror, whether it’s ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ ‘The Munsters,’ ‘Bewitched’ or any of those other gateway movies or stories.

“It’s fascinating how people seek queerness — and where they seek queerness,” Fuller added.

“Queer for Fear” begins its look at the history of queer people’s relationship with horror — and adjacent genres like thriller and sci-fi — well before Fuller’s beloved 1960s sitcoms, with an in-depth review of the lives of late 19th century writers and reputed queers Mary Shelley, Oscar Wilde and Bram Stoker. With the help of personal correspondence and other archival materials, the series’ commentators relate how Shelley’s “Frankenstein” was influenced by her polyamorous, sexually fluid relationships and how Wilde, after having penned “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” eventually became a martyr of Britain’s anti-gay penal code. They also detail how Stoker’s “Dracula” was a product of his uneasy relationship with his queerness, which eventually led him to become a vocal opponent of homosexuality.

All the while, the commentators, although serious about their history, never veer into the somber, thanks to plenty of colorful analysis. In one scene, for instance, “Dear White People” writer Justin Simien gives his thoughts about the conflicted author of literature’s most famous vampire: “Bram Stoker was kinda cute. … Like, he kinda could get it, just a tad bit.”

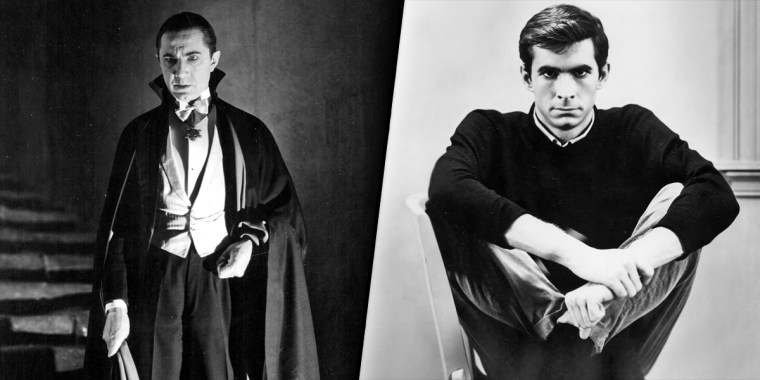

As the series moves into the 20th century and through the silent film era, touching on cinematic works like F.W. Murnau’s “Faust” and “Nosferatu,” such moments of levity keep viewers engaged while they’re soaking up early Hollywood’s rich queer history. When it arrives at Universal Pictures’ classic monster movies — exemplified by the 1931 films “Frankenstein” and “Dracula” — there are some particularly humorous reads, including one from the drag queen Alaska, who isn’t the only “RuPaul’s Drag Race” alum in the series.

“Whether you’re ideologically queer or sexually queer, you might relate to the monster’s narrative, because you, too, have felt ‘outsidered’ or villainized in some way.”

— Bryan fuller, 'queer for fear' executive producer

“The Dracula costume kit is basically drag. You have face paint, and then you have blood-red lips, and then you slick your hair back. You put on a cape, you put on fancy antique jewels, and then you go to live in a castle,” Alaska says, describing the Dracula archetype pioneered by actor Bela Lugosi. “And you can turn into a bat. So this, to me, is the experience of being a gay man.”

As Alaska’s assessment demonstrates, “Queer for Fear” isn’t interested in just exploring how horror has provided a haven for queer creatives. It makes the case that regardless of whether a certain monster story, thriller, sci-fi work or other piece of genre fiction is explicitly intended to appeal to an LGBTQ fan base, queer people have always known how to see themselves in a work of art.

“When we look at these horror stories and are able to project ourselves onto the narratives in some way, that is still valid. That’s part of the audience experience,” Fuller said.

Fuller, who has also worked on multiple “Star Trek” iterations, including as the creator of “Star Trek: Discovery,” has a uniquely democratic take on how an audience’s relationship to a work is, perhaps, as significant as the work’s intended meanings.

“There are elements of certain franchises that take advantage of what the audience is bringing to them, in terms of their associations and their attachments, whether it’s ‘Star Trek’ or ‘Star Wars’ or Marvel,” Fuller said. “Sometimes, the audience has to build the bridge to those stories, because there isn’t explicit representation. We, as queer people, are used to building that bridge.

“If you are a queer person telling a story, it’s going to be informed by your queerness, whether it is represented explicitly onscreen or not. There is going to be a queer point of view to every story that James Whale tells; there is a queer point of view to ‘Frankenstein’ and ‘Dracula,’ because Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker were queer people,” he said. “But it’s also totally valid for you to see queerness in Luke Skywalker.”

Fuller added, “For me, as an audience member, if somebody isn’t explicitly heteronormative, then they are game for a queer read.”

Alfred Hitchcock’s films, which are featured heavily in the series, have that in common with the famous sci-fi and superhero franchises. With characters like the murderous men in “Rope” and “Strangers on a Train” to the cold-blooded Mrs. Danvers in “Rebecca,” the horror auteur’s works are filled with queer subtext, taking advantage of what his viewers and, in many cases, his stars brought to film houses in the era of morality policing and psychoanalysis.

“Queer for Fear” gives special attention to Hitchcock’s 1960 masterpiece, “Psycho,” which starred Anthony Perkins as the gay-coded, mother-obsessed killer Norman Bates. A candid interview with Perkins’ son, Oz Perkins, elucidates the parasitic relationship between Hitchcock and his closeted star, who the director almost surely knew was queer.

“It was like his coming out and his funeral at the same time. In one swift move, the whole jig was up,” Perkins says, referring to his father’s disappearance from the industry in the wake of the film’s popularity. “‘Psycho’ was no good for him. It was too good. It was too good, and therefore it was no good.

“It had damaged my father’s career, because now no one could see him as anything else. There was no freedom in 1960 to say, ‘Oh, and by the way, the reason why I’m so great in this role [is] I’m just like that.’”

Anthony Perkins was one of many screen stars of the era who stayed in the closet out of fear of public backlash, a situation perpetuated by the Hays Code, which sought to police the morality of film productions by banning certain subject matter, including homosexuality. Because of the Hays Code, LGBTQ creators and those, like Hitchcock, who wanted to include those themes had to do so through subtext, which counterintuitively gave birth to some of the most essential queer horror ever made.

“There’s a quote in the first ‘Scream,’ like, ‘Horror movies don’t create killers; horror makes killers more creative,’” Fuller said, paraphrasing a quote from the film’s climax. “The Hays Code didn’t create queer content, but it made queer content more creative.

“It was working extra hard to try to mind-meld with the audience, because typical aspects of communication couldn’t be used. And if you got it, then it meant something extra special,” Fuller added. “We see that in simple terms with the crime procedural, where you set up a character and the audience is like, ‘Oh, I think it’s that guy.’ And then, when it is that guy, they win.

“When you take that parable and apply it to queerness, you get that same level of satisfaction — of seeing something that perhaps not everybody else can see.”

In addition to the many queer stereotypes used, one of the most common elements of such coded horror films is that the characters, for morality’s sake, are banished to the fringes of society and typically destroyed for their perceived monstrosity — whether they’re sapphic-leaning vampires or flamboyantly dressed psychopaths. From there, it’s not hard to make the leap to why queer audiences have found them so compelling.

“There’s something about the commonality and the relatability of the outsider experience,” Fuller said. “Whether you’re ideologically queer or sexually queer, you might relate to the monster’s narrative, because you, too, have felt ‘outsidered’ or villainized in some way.”

Or, as the author Carmen Maria Machado says in the series, “If you’ve been on the other side of the pitchfork, you’re probably sympathetic to the monster.”