Where you grew up may influence how you speak. High in the mountains, languages contain short bursts of sound, says a new study. Why? Maybe cliff dwellers needed to keep their throats from drying out.

Caleb Everett, an anthropological linguist at the University of Miami, studied the correlation between languages spoken at high altitudes and the use of distinctive sounds called ejectives — bits of speech produced by air bursts from the back of the throat.

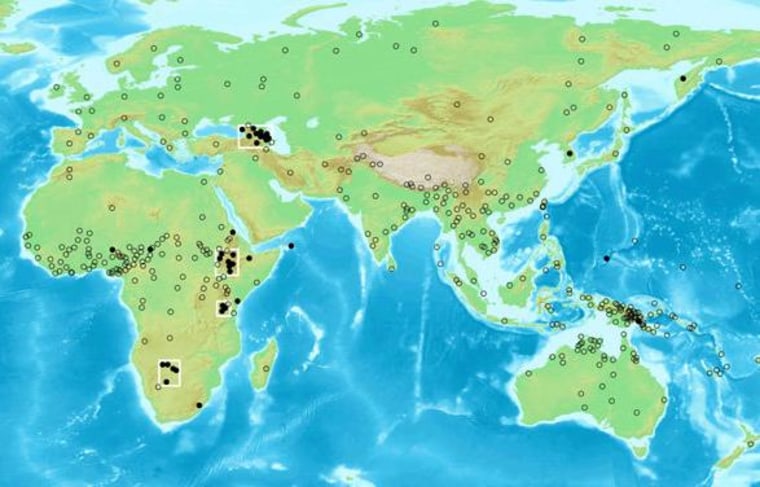

After looking at the presence or absence of ejectives in 567 languages, Everett found that 92 of those used ejectives. Sixty-two percent of languages that used ejectives were spoken by people living in land areas above 1500 meters (4921 feet) or lived within 200 kilometers (124 miles) of a high area.

“What I think is clear is the correlation is off the charts,” Everett told NBC News. English and European languages lack ejectives. The closest you get is the sound of a hard “k” in “kha”, he explained. But Athapaskan (an indigenous language spoken in North America), Mayan and Lezgic (spoken in the land belt between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea) do. Tibetan dwellers dont have ejectives, however, and Everett doesn't know why.

The reason that ejectives may thrive in higher altitudes is a bit fuzzy, too, though Everett does make some initial suggestions in his paper, published Wednesday in PLOS ONE.

Ejective sounds "theoretically" reduce water vapor loss while speaking, Everett explained, which might be a health benefit in dry, high places. Also, the decreased atmospheric pressure at high altitudes makes it physiologically easier to create an ejective sound, because it involves pushing a burst of air out from the back of your throat, out from the pharyngeal cavity. “What is admittedly very open to debate is how this effect may have come into existence,” he said.

Everett's work is not without criticism, however.

“The statistical methods are fine but the real-world reasoning is flawed,” Claire Bowern, a linguist at Yale University wrote to NBC News in an email. The influence of geography on language has been well documented, she agrees, “Related languages tend to be geographically close to one another,” and speakers of different languages tend to borrow words from each other.

“The trouble is that there are enough language features that it's very easy to find correlations between some aspect of language and some aspect of population structure or geography," she wrote.

"Evidence for Direct Geographic Influences on Linguistic Sounds: The Case of Ejectives" by Caleb Everett was published in the June 12 edition of PLOS ONE, published by the Public Library of Sciences One.

Nidhi Subbaraman writes about science and technology. Follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Google+.