For over 45 years, award-winning journalist Jon Alpert has been fascinated by the people and culture of Cuba. He began visiting the island in 1972 as a documentarian, wanting to see for himself whether the revolution was working. Through many visits, Alpert came to befriend Cubans as well as Fidel Castro himself. Alpert’s latest film, "Cuba And The Cameraman" premieres on Netflix and in select theaters on Friday, November 24 – one day short of the first anniversary of Castro’s death.

Alpert, 68, first went to Cuba as a young community activist. “Initially I was very curious about Cuba; we were doing community organizing in Chinatown and the lower east side (of Manhattan), fighting for better housing, fighting for better schools, fighting for better jobs – and failing spectacularly,” he told NBC News. “And a lot of the things we were fighting for, we heard were being implemented in Cuba but we also heard that people were unhappy about what was going on. We decided we wanted to see for ourselves.”

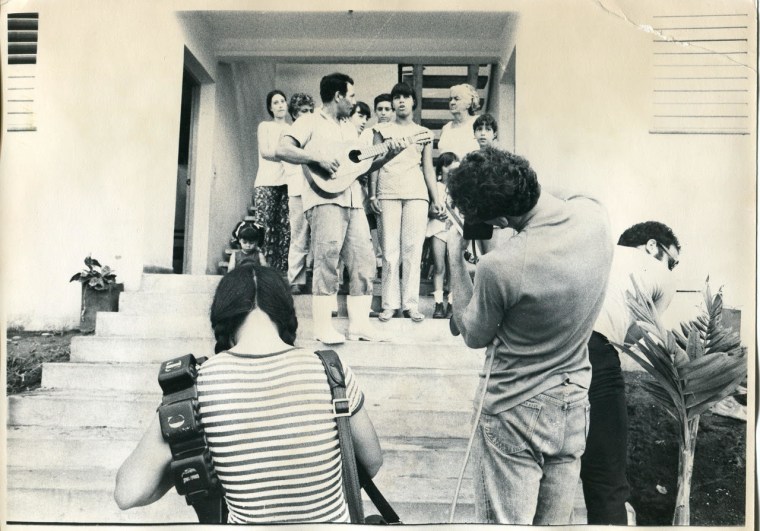

This began a nearly five-decades long connection with the island. Alpert’s camera crew, in the early days, was his wife and her cousin, usually with his young daughter in tow. Because their equipment was so cumbersome, they wheeled it around Cuba in a baby carriage, a makeshift technique that proved fortuitous when Castro noticed them.

“He saw these strange young people pushing a baby carriage around, and he wanted to know what was going on,” Alpert said. “Despite the efforts of his security guards to sort of control him, he broke through and came over to see us.”

Although Alpert had been seeking access to Castro for several days, when the Cuban leader approached him, the filmmaker became tongue-tied. Later, Alpert’s wife and her cousin chastised him, pointing out that they were able to do their jobs of holding the microphone and the camera, while he was fumbling his duties. “And so humbled, the next time I got near Fidel, I almost tackled him,” Alpert recalled. “Ever since then, he took a shine to me and we became good friends.“

Besides Castro, Alpert follows three families through the ups and down of modern Cuban history. “It is a very unique subsample (of people), and a very personal subsample, to some degree a sample based on serendipity and happenstance,” he said. “These are the people I happened to meet. They weren’t picked out by the government, they were picked out by fate. They were the people I bumped into who became my friends, who I decided to follow.”

"Cuba And The Cameraman" shows what it was like to live on the island through good times and bad. In the early 1970s, Alpert notes in the film, “The revolution seems to be working.” Ambitious education, housing, and social programs are being implemented, and many people seem euphoric about the future of their country. Even then, though, rural families lacked electricity and running water.

Alpert also chronicles dissatisfaction among Cubans, including the increasing number of people who want to leave. The collapse of the Soviet Union, which had been providing $8 million a day to Cuba in subsidies, leads to food shortages, a lack of medical supplies, and power blackouts.

Alpert’s film captures the impact of such upheaval on ordinary Cubans. An encounter with a schoolgirl leads to a follow-up visit 16 years later, when she is happily ensconced in government housing with children of her own.

Yet when Alpert looks her up again, on a subsequent visit, she is gone; living in Tampa, Florida, her relatives say. Another time, Alpert sets out to find a former acquaintance, only to learn that he has been imprisoned for buying and selling goods in the black market.

Looking back, Alpert said “I have to say that I was rooting for them (Cuba) to succeed in every area.”

Through the years, Alpert managed to get unique access to Castro. Alpert was the only American journalist on the plane that brought the Cuban leader to New York City for an address to the United Nations in 1979. In 1992, when Alpert’s daughter admits that she is skipping school to come to Cuba with her father, Castro writes her an absence note to take to her teacher.

Alpert’s daughter, Tami, guesses that she visited Cuba about a dozen times growing up. “Now I realize it was unusual. But at the time it was just my life,” she said. “Everyone else, my friends, they would go to their grandma’s over the holidays, but meanwhile we would be jetting off to Cuba.”

Tami Alpert estimates that she has been to 50 or 60 countries with her father, who has reported from all over the world (he even took her with him to Afghanistan). “One of the things I loved about Cuba was that it was, for years, completely untouched and uninfluenced by America,” she said. “It was interesting to see how people lived.”

Early reviews for "Cuba And The Cameraman" have been generally favorable. A reviewer for The Hollywood Reporter called the film “a warm and engaging primer on a complex and controversial subject.”

A columnist for the Houston Press noted that “even under restrictions, he (Alpert) always finds something fascinating to show.” Alpert’s rare footage captures emotional family reunions as Cuban-Americans were allowed to visit relatives on the island in 1976, as well as soon-to-be exiles who say simply, “I want to live in a free country.” Alpert records how, more recently, the tourism industry has transformed Cuba, and notes the appearance of ATMs, wi-fi hotspots, and people taking selfies on the streets of Old Havana.

Alpert describes Castro as a person with “insatiable curiosity” and “a tremendous amount of energy.” At various times, Alpert was able to coax the Cuban leader into showing him his bare chest, the contents of his refrigerator, and his suite at the Cuban Mission in New York. On one flight back to Havana, Castro tells Alpert that “I see us as a family.”

Alpert is aware that some people might not warm to the idea of his befriending a dictator who tolerated no political dissent, and who showed little regard for civil and human rights.

“I very much understand why people who’ve had bad experiences in Cuba, people who grew over the years to dislike Fidel, even to hate Fidel, would watch this movie and have a completely different perspective on life in Cuba and Fidel’s legacy,” Alpert said. “But the people who fit that particular category, and there have been many of them who have seen the film, understand that from my perspective as a reporter, that there is a lot of objective information. There are a lot of things about Cuba (in the film) that no other cameras have seen before, that tell a lot about the reality, some of it very unpleasant. So even people who didn’t like Fidel like this movie.”

Alpert was one of the last Americans to see Castro alive, in a three-and-a-half hour visit that authorities did not allow him to record. Although he had been promised an on-camera interview with the ailing leader in January 2017, by November Castro had passed away, marking the end of an era.

"Cuba And The Cameraman" will be shown at the Havana Film Festival in December, and Alpert will be there. He is especially proud that the screening will be in a large theater and thus open to the public.

Alpert is the recipient of sixteen national Emmy Awards and two Academy Award nominations. He is the co-founder of New York City’s Downtown Community Television Center, a nonprofit media arts education center. He has covered stories from Cambodia to Ground Zero to Egypt, and made films for HBO, ESPN, and PBS.

Alpert hopes that audiences respond positively to his latest film. “I think you can have a very interesting single visit to Cuba. But to watch basically what was a unique social experiment over a period of time, you can understand what is working, what’s not working, and the challenges in trying to implement these ideas,” he said.

“I was very curious and thought it would be a good way to share with the American people if we could look at the revolution through their (the Cuban people’s) eyes… And it is not a bunch of professors talking about economic incentives,” Alpert added. “It is a peasant trying to feed his family. It is somebody wondering why the water doesn’t work today. These are things that we as New Yorkers deal with all the time, and by basically sharing my friends and their experiences, I thought it would be a good way to tell the story of Cuba.”