It's been almost a century since historian and scholar Carter G. Woodson created Negro History Week and almost a half-a-century after it was expanded to Black History Month.

Through the ensuing years, there's been debate over the need for such a designation, with some critics maintaining that black history is American history and others saying it's evolved into nothing more than scholars making speeches and sitting on panels and businesses using the month for marketing and promotional purposes.

But to the question of whether Black History Month is still relevant, LaGarrett King, an associate professor of social studies education at the University of Missouri, Columbia, answers, “Absolutely yes.”

King, whose research focuses on K-12 black history education, says the criticism, much of it from conservative historians, ignores that most Americans are not learning the nation's real history when it comes to slavery and the trajectory of the black experience in America.

“For many decades, the history narrative taught in U.S. schools was that we had slavery, but only a few people owned slaves, we restricted it to the South — and there were only a few bad people who were slave owners," said King. "That narrative continues in some places."

In some of his research, King points to a textbook recently used in Texas schools that describes the trans-Atlantic slave trade as the immigration of “millions of workers from Africa to the southern United States to work on agricultural plantations.”

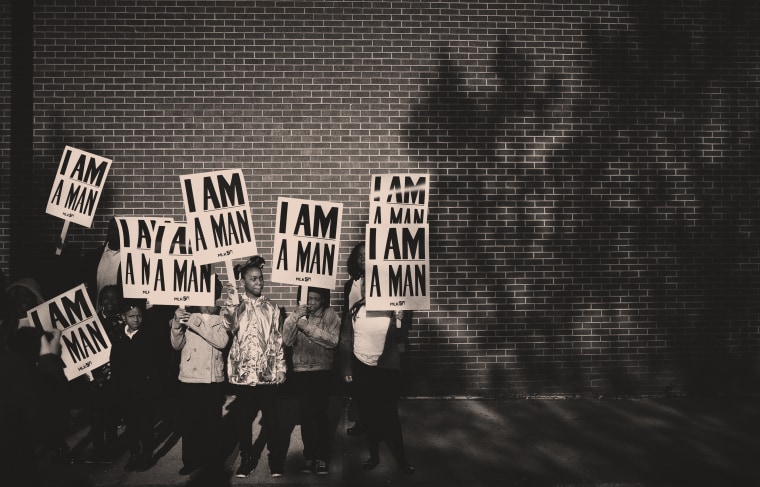

King said that when it comes to studying Martin Luther King Jr., for example, "we learn only about his nonviolence. We don’t learn about his evolving as an anti-war leader.”

"With slavery, we don’t learn about Nat Turner and other slave-led rebellions," King said. "It is so important that our story is told and is told fully. That is who we really are.”

Daryl Michael Scott, a history professor at Howard University in Washington, said there are 50 state boards of education, and within each state there are local boards.

“All of them have input on what history is taught and how it is taught," said Scott. "That puts you in a struggle to have your point of view, your history honored and disseminated properly.”

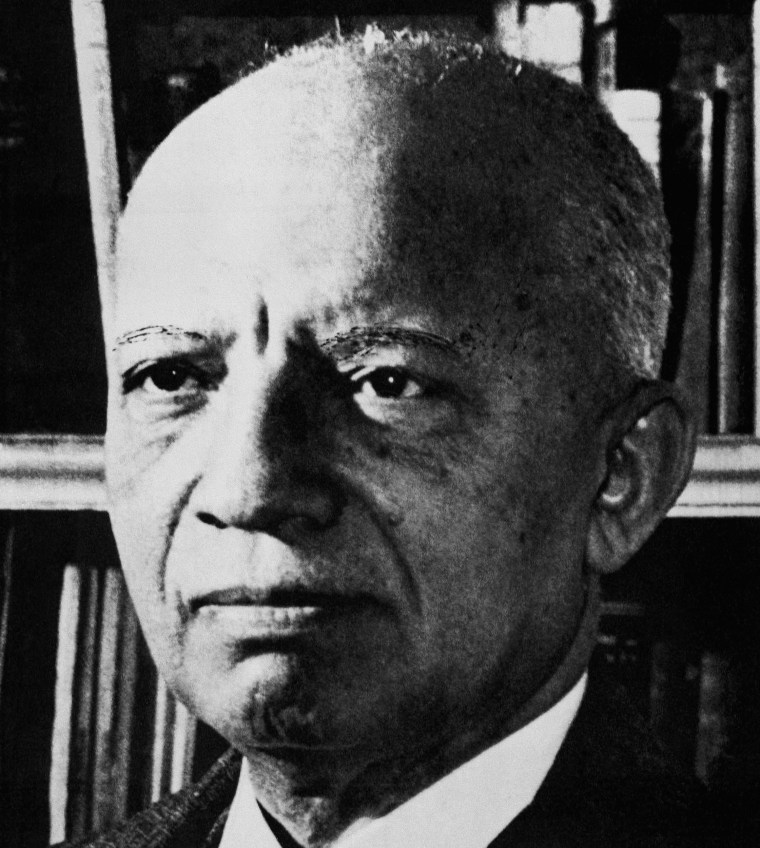

When Woodson pushed the idea of setting aside a week to study and acknowledge the contributions and accomplishments of black people to the development of the United States, he always saw it as lasting longer than seven days, Scott said.

“He always thought about it as a 365-day endeavor,” said Scott, whose research and work with the Association for the Study of African American Life and History has led him to read almost all of what Woodson has written.

Woodson wanted to ensure that black Americans’ historic contributions were learned throughout the school year. He also wanted to improve race relations, and, most important, he wanted to make sure those contributions were not erased from the country's history.

“He had a dim view of a people’s history eliminated because he believed genocide had taken place” with Native Americans in the United States, Scott said. “He wanted to make the case that blacks had contributed to human history.”

Today, only about 20 percent of white students take ethnic studies classes in college, King said. In K-12 grades, “a lot of teachers don’t have the knowledge to teach history in February, let alone throughout the school year because they were educated in the U.S. education system.”

“History,” King continued, “is about identity, about the first time we learn about ourselves. It is the first time that people learn about those who are ‘other’ than they are. The way we teach about ‘other groups’ is important.

For the historians King and Scott, black history and its relevance is all about the U.S. education system.

There has been progress. Narratives on some topics in black history are more similar than different across the states, despite the use of different textbooks.

But in a Jan. 12 article, New York Times education writer Dana Goldsteincompared 43 history textbooks used in middle schools and high schools in California and Texas, and showed that the texts from the two states did not “deal frankly with the fact that many of the Founding Fathers were slave owners.”

In addition, the textbooks used in Texas described the movement of mostly white people from cities to suburbs in the 1950s as a positive migration. The California texts included a narrative that “the suburban dream was not accessible to many African-Americans because of redlining, restrictive deeds and other policies.”

The bottom line, said Beverly Daniel Tatum, a former president of Spelman College in Atlanta and a clinical psychologist who has researched and written books on racial identity, is that there are many “marginalized people whose full stories have been left out of our history.”

“When you have knowledge of your history, it changes your perception of yourself,” Tatum says. “I am not teacher bashing here, but many of those educators are simply not qualified to infuse black history throughout the full curriculum. An important question is, How do we ensure that the educators have the resources they need to do the job that needs to be done?”

At least seven states have mandates with oversight committees regarding teaching black history. Some, according to King, such as New Jersey’s Amistad Commission, are better than others in providing system-wide training and resources for teachers. In too many cases, politics gets in the way of substantial and meaningful changes.

New Jersey was the first state to pass the Amistad legislation in 2002. Its Amistad Commission spells out what students are expected to learn in each grade level, and school districts choose the curriculum to help students achieve the goals, which are required by law to be updated every few years.

The commission also offers teaching resources, summer institutes for teachers and textbook recommendations for primary grades. A recent new initiative provides teachers with visits to historic sites associated with the transatlantic slave trade.

Stephanie James Harris, who has served as executive director of the Amistad Commission since 2007, said that a key is that the commission has staff and resources dedicated to do the work.

“We have a clear plan and a course of action,” Harris says.

Scott, the Howard professor, says that history is always up for re-evaluation. “Each generation writes its own history, rethinks its past,” he says.

But we needed Black History Month in 2009 after Barack Obama was elected president, Scott said.

“In 2020, we have neo-Nazis gaining traction in this country," he added. "We need Black History Month more now than ever.”