This time last year, Col. Brian Biggs of the Air Force Reserve was helping to dispatch refrigerated trucks and body bags to pandemic-ravaged New York City and other places in the Northeast that needed them the most.

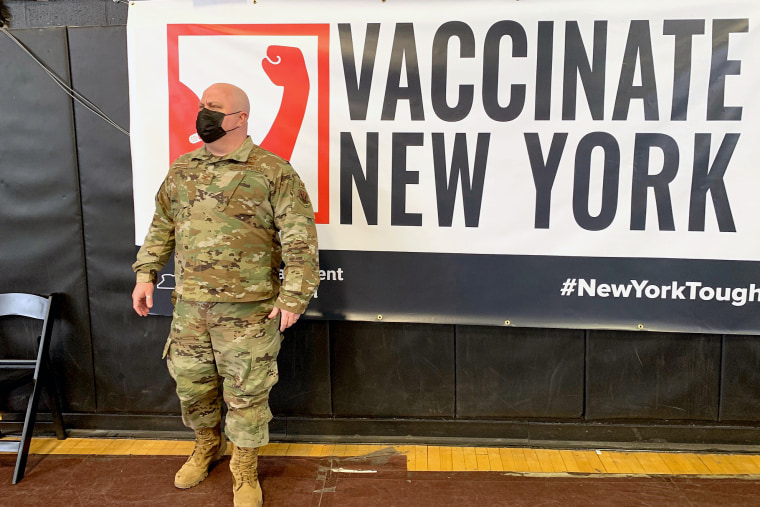

Now, Biggs’ mission is helping to ensure that needles loaded with the Covid-19 vaccine get into the arms of as many people as possible in the Brooklyn borough of New York City.

“The difference between now and then is night and day,” Biggs, 45, said in an interview Wednesday. “Then, every day I could count on a daily dose of depression. Now I get a daily dose of hope.”

Biggs, a Nebraska native who now calls Madison, Connecticut, home, is one of the more than 10,000 members of the United States military who were called on to wage war against an invisible enemy that killed more Americans in one year than the country lost during nearly four years of fighting during World War II.

Much of the help the military provided at the height of the pandemic was medical, and the men and women who answered the call often did so at great risk to themselves. More than 176,000 of them tested positive for Covid-19, 1,588 were hospitalized and 24 died, according to the latest Department of Defense figures.

Biggs gets his shot of daily optimism at the Medgar Evers College Preparatory School, where he helps coordinate the community vaccination effort.

“When I walked into the gym for the first time, I was just amazed at the organized chaos,” he said. “The people coming in were predominantly people of color, people from underserved communities. You have to remember, Brooklyn was hit especially hard by the pandemic.”

Biggs has been in the Air Force for 22 years, all but four of them as a reservist. He's usually assigned to assist the state of Vermont with emergency preparedness,

“Our bread and butter, as it were, is dealing with the aftermath of hurricanes and other natural disasters,” he said. “We arrive at homes that have been destroyed and deal with people who are destitute. It’s often very depressing.

"Here, people were smiling and happy and darn-near dancing after they got their shots. The people were excited to see the U.S. military in their neighborhood.”

Biggs, who received his second dose of the vaccination last month, said he expects to be at Medgar Evers through April.

“We have 3,250 appointments just today, and that includes 30 to 50 that are 16- and 17-year-olds, which I think is great,” he said.

In his spare time, he and his wife, Dawn, run a nonprofit called “Random Tuesday” that stages “virtual running events” with “Harry Potter” and “Dr. Who” themes to get people to exercise and to raise money for worthy causes.

Biggs previously served in Afghanistan and Kyrgyzstan, but says he was not always on the front lines of this fight.

“I did most of my work from Fort Living Room,” he said modestly, adding that the "emotionally taxing work" of collecting the bodies of Covid-19 victims fell to members of the National Guard.

“No soldier was allowed inside the homes, but they would collect the bodies from the threshold and then it was on to the next stop, on to the next stop, on to the next stop,” Biggs said. “It was a hard mission.”

But the times that Biggs ventured out into the field to inspect staging sites and to help the Federal Emergency Management Agency and others identify potential locations for “mass cold-storage of remains” were, in his words, “a surreal experience.”

“In the first week of April, I was checking into a hotel in Massachusetts and as I walked inside the clerk said, ‘Good afternoon, Mr. Biggs,’” he said. “They knew my name because I was the only guest checking in that day.”

Biggs said he got his first coronavirus briefing in February 2020.

“The thing I took away from it was that there was a great concern but also that we didn’t know fully what to expect,” he said. “Some experts were already saying it was going to be bad, others were saying it might not be so bad. But it was always in the spectrum of bad.”

Five weeks later, the country started shutting down.

“I remember that it was Friday the 13th, and my daughter came home from the eighth grade with all her stuff,” Biggs said.

Ten days later, he received new marching orders that came with an ominous sounding name — mortuary affairs and fatality management.

“Essentially, my job was helping coordinate the collecting of bodies, the storing of bodies and the dignified delivery of bodies to the next of kin,” he said.

New York City, which was one of the hot spots in the early days of the pandemic, quickly became the focus of Biggs’ attention.

“The first fatality estimates from the medical examiners were for 10,000 deaths in New York City alone in the 60 days between the end of March and the end of May,” he said. “That was a hard wake-up call for us. We knew that as the numbers got higher, the states were not equipped to handle that level of fatalities. The morgues and funeral homes were already at capacity.”

Right around then, the first refrigerated trucks designed to store bodies and which came to be known as “reaper trucks” were dispatched to New York City.

“It was a scramble for limited resources,” Biggs said. “In particular, human remains pouches (body bags) and N95 masks were in incredible demand.”

With scientists still uncertain about whether corpses could spread the disease, mortuary workers were zipping the victims into two bags at a time for extra protection, he said.

Biggs said one of his proudest moments came when he learned a National Guard company was heading to New York City without enough personal protective equipment, and he was able to pull a few strings to secure the needed gear.

But the dilemma from Day One was what to do with all the bodies. Nearly 52,000 people in New York state died due to Covid-19, most of them at the start of the pandemic.

“Early on, one idea that was floated was to use ice skating arenas as cold storage,” Biggs said. “That’s a bad idea. Human cells do not respond well to freezing temperatures. We wanted to make sure families got their loved ones back in a dignified manner, although we had no idea when that would be.”

He said he wasn’t surprised that cities and states were not prepared for so much death.

“All the cities and states have capacity when the death rate is constant,” he said. “There is enough morgue space. But here were thousands of deceased and that put real stress on the system. You couldn’t turn them over to the next of kin because the funeral homes were overwhelmed. And in places like Vermont, bodies couldn’t be buried in April because the ground was still frozen.”

The work, Biggs said, was grueling: “It started when the sun came up. Then it was meetings, phone calls, teleconferences, and all the while I was doing my civilian job, as well.”

He said he never felt overwhelmed because he had faith in FEMA and the Defense Department to handle this crisis, "but we didn’t know when we would reach the peak.”

“We didn’t know if it was going to be 10,000 dead or if it would be 10 times more than that. And every day, I got my daily dose of depression.”

Then-President Donald Trump was downplaying the danger of Covid-19 and pushing to reopen the country over the objections of public health experts and much of the medical establishment.

Asked about that battle, Biggs declined to wade in with an opinion but insisted, “I did not see any politics in my orders.”

“There was a lot of conflicting theories from the experts about when normal life could return, when we would see a flattening of the curve,” he said. “But once it started spreading across Florida, across Texas and other states in the South and West, I knew this was not going to wrap up by Labor Day.”

Biggs' role in this drama ended in June as the number of coronavirus deaths flattened across the Northeast. He returned to civilian life until his most recent assignment at Medgar Evers.

Asked what he would tell his grandchildren about the pandemic, Biggs thought a moment, then said, "Americans don’t give up.”

“We press on,” he said. “Yes, there are political and ideological divisions. But on the whole, we come together. We persevere.”