There are 19 years worth of Christmas presents waiting for Kevin Ott if he ever gets out prison.

The Oklahoma man was convicted of trafficking after he was caught with just over 3 ½ ounces of methamphetamine, roughly the weight of a deck of cards, in 1996.

The state’s three-strikes law forced a judge to send Ott to prison for life without parole — but his mother, Betty Chism, has never given up hope that he might be freed.

Each Christmas, she buys him gifts and then sets them aside, dreaming of the day she can give them to her son, who also has faith that he will one day walk out of prison.

"I've survived by knowing deep down inside of my heart that I will go home someday," Ott, 53, told NBC News in an interview at the Oklahoma State Reformatory, where he's incarcerated. "That time is closer than it's ever been before."

For two decades, courts across the U.S. have imposed long-prison terms on those caught with relatively small quantities of drugs.

But now the budgetary and human cost is fueling a bipartisan effort to fix a criminal justice system seen as expensive and ineffective.

President Obama has joined liberal and conservative lawmakers in pushing for reform, and this month 6,000 drug offenders were released early from federal prisons. Obama says they deserve a second chance — a chance that Kevin Ott isn’t getting.

That's because Oklahoma's recently passed reform of its three-strikes law is not retroactive and does not apply to him or more than 50 other drug offenders sentenced to life without parole.

As it stands today, Ott's only chance of seeing his family again as a free man and unwrapping all those presents is a Hail-Mary legal move, or an act of mercy by Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin.

"I'm not sentenced to stay 40 years, or 50 years, get good time and get out," Ott said. "They sentenced me to die in prison."

‘I Was Wrong’

In 1996, police caught Ott with meth and a handgun in his trailer. He had two prior felonies for drug possession, one for having marijuana plants, the other for a bag of meth police found in his pocket as he left a bar.

Ott had worked a series of blue-collar jobs, from oil-rig roughneck to carpenter. He says he started using and selling meth after he got laid off. His addiction fueled one bad choice after another.

"I am smart enough to know I was wrong in all I was doing," Ott said.

Prosecutors charged him with drug trafficking for those 3 ½ ounces of methamphetamine. His conviction became his third strike, forcing the judge, under state law, to sentence him to life without parole. (He was also convicted of possessing the gun, a violent crime under state law, but the drug offense triggered the mandatory sentence.)

Betty Chism, Ott’s mother, wasn't in the courtroom at his sentencing in 1997. She had tried to convince judges, district attorneys — anyone who would listen — to divert her son into treatment before his second drug conviction.

"I asked them please, just let me get him some help," Chism, 71, said. "I would gladly cover the cost if they would just allow him rehabilitation. They just wouldn’t discuss it with me."

Chism’s brother called to tell her the news. Ott had received life without parole, second only in severity to the death penalty — a sentence typically reserved for murderers and rapists, the state’s most violent criminals.

He would have no chance of ever getting out. No parole, no relief. No way to earn credit for good behavior that could win him early release — unlike killers and sex offenders.

"I knew he was going to jail," Chism said. "And never did I think he didn't deserve to be punished. But never in my wildest dreams did I ever think that such a thing as that could happen."

Tough On Crime

Oklahoma wasn't alone in taking a hard line on repeated offenses.

In the 1990s, tough-on-crime sentiment swept the nation as high crime rates and drugs plagued U.S. cities and towns. States implemented harsh punishments, including three-strikes laws that could sentence people to life for minor crimes if they followed more serious ones, and laws that levied heavy mandatory sentences, including for drug offenses. The federal government followed suit. Prison populations began to balloon.

In 1989, Oklahoma lawmakers passed a three-strikes law that mandated life without parole for a drug-trafficking conviction if an offender had two previous drug felonies.

Trafficking is broadly defined in Oklahoma. Prosecutors there routinely charge defendants with trafficking based on the weight and type of the drugs they're caught with — including 20 grams of methamphetamine and five grams of crack cocaine.

The ACLU estimates that more than 3,200 inmates around the country are serving life without parole for nonviolent crimes, such as drug and property crimes.

In a 2012 report, the ACLU found that in some cases men and women were sentenced to life without parole for such minor crimes as shoplifting or possessing a bottle cap with a trace amount of drugs on it.

"When these laws were passed, lawmakers didn't necessarily envision that they would be used against somebody who was selling a small amount of drugs to support a drug addiction," said Jennifer Turner, human rights researcher with the ACLU, who authored the report. "This is a waste of human life and of taxpayer dollars. … And it doesn't work."

19 Years

As the years passed, Chism watched her son change.

His anger lessened until it became a slow drip. He watched as people convicted of more serious crimes walked free.

Determined that Kevin would one day come home, Chism and her two daughters, Angie and Brandi, continued to work on his case.

For awhile, Chism blamed herself. She wondered if she should have surrounded him with better role models, or sent him to treatment.

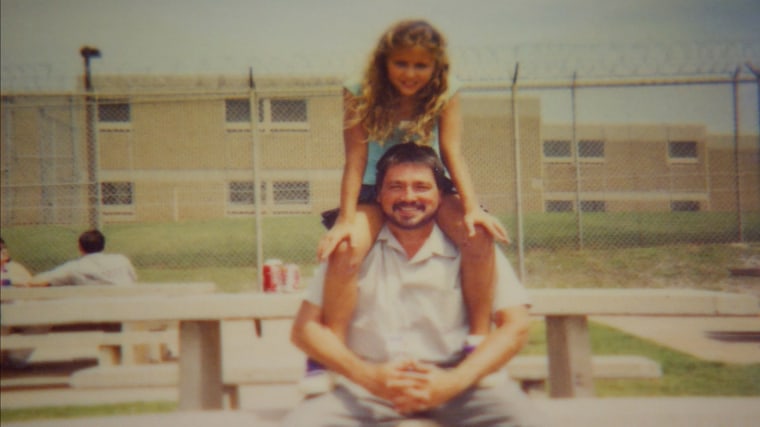

But guilt gave way to acceptance. The family adjusted to a new normal — weekends spent together in prison visitation rooms, purses full of quarters for the vending machine.

"Nineteen years we've done this," Chism said. "Not one single year has it been any easier."

She held onto the belief he'd get out some day. "I will never, as long as I have a breath in my body, I will never give up that hope," she said.

But tragedy challenged that belief.

In 2001, Ott’s sister Brandi died on her way to visit him. She was killed in a car wreck at a flashing light just down from the prison.

After that, the holidays, already painful, became harder.

"It was just so sad without Brandi, and without Kevin," Chism said.

Hope

Meanwhile, Oklahoma's prisons swelled. It now has the third-highest incarceration rate in the country.

Tough laws, including one that requires certain offenders to serve 85 percent of their sentence before being eligible for parole, kept prisoners in longer and pushed two-thirds of the state's prisons over capacity.

State legislators grew concerned about growing corrections costs and began to push for reform.

This spring, Gov. Fallin signed The Justice Safety Valve Act, doing away with some mandatory minimum sentences, and allowing judges to divert more offenders into rehabilitative programs, like drug courts.

Another law reduced the minimum sentence for drug trafficking after two felony drug convictions from life without parole to 20 years in prison.

But it wasn't politically feasible to make the law retroactive, said the bill's sponsor, Rep. Cory Williams (D.-Stillwater).

"We haven't been able to move the needle as much as I wanted to," Rep. Williams, a former attorney, said. "But I think the mood is now changing."

Regardless, that legislation led Ott and dozens of others to submit commutation applications — a rare form of clemency that shortens a prisoner's sentence — to the state Pardon and Parole Board.

It's a process fraught with hurdles.

If the board recommends commutation, Gov. Fallin has the final say on whether it goes through.

Last month, the board heard requests from at least two prisoners serving life without parole for drug trafficking. In one case, they denied commuting the sentence of Leland Dodd, who was sentenced to life after arranging a marijuana sale in a reverse sting operation. In another, the board commuted the sentence of a terminally ill man serving life without parole for drug trafficking, to life with the possibility of parole, for which he will have to re-apply to the board.

The board has agreed to hear Ott's application asking it to commute his sentence and let him free. The hearing is scheduled for next month.

Gov. Fallin has been praised on both sides of the aisle for her willingness to support criminal justice reform. But it is unclear how she will treat the commutation requests of such prisoners. She has not granted a commutation since 2012.

The governor declined to speak to NBC News or answer questions about the commutation process.

In 2011, the Pardon and Parole Board voted to commute the sentence of 65-year-old Larry Yarbrough, who was sentenced to life without parole for drug trafficking. Gov. Fallin denied the request.

Today, Ott and his family feel that his best chance at release lies with the courts. Ott has also filed for post-conviction relief in Cleveland County, where he was convicted, arguing that he should be released on the grounds that the law that sent him to prison for life is now obsolete.

In many ways, this is the family’s last — and best — hope.

"I don't believe my son is supposed to die in prison," Chism said. "I believe he's supposed to come home and be the man he can be."