COX’S BAZAR, Bangladesh — Six days into Mohammad Hossain’s boat journey to a new life, the engine broke down.

Hossain, 17, a Rohingya refugee living at a camp in Bangladesh, had paid brokers $1,000 to take him across the Andaman Sea to Malaysia, a trip that was supposed to take two weeks. Now, he and about 150 other people crowded in the trawler had little hope of reaching their destination, and conditions were getting increasingly desperate as they drifted at sea.

The brokers had stopped providing water and food, leaving Hossain and the others to survive on rain and seawater. Passengers who argued or asked for something to eat were “subjected to inhuman torture” by the brokers, Hossain told NBC News in January during a video call with his family at the Kutupalong refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, a district in southern Bangladesh. At least 20 people died, he said, including some who jumped into the water.

On Dec. 26, more than a month after he had left, Hossain finally made it to land — although not where he had intended to go.

“Thanks to Allah,” he said, “I have reached Indonesia alive from the doors of hell.”

Almost 1 million mostly Muslim Rohingya refugees remain stateless in Bangladesh years after having fled neighboring Myanmar, a majority-Buddhist country where they are not considered citizens and were the targets of a deadly military campaign that the U.S. has declared genocide. Seeing no future in Bangladesh, where they are not officially allowed to work and have limited opportunities for education, growing numbers are risking their lives on dangerous boat journeys to countries in Southeast Asia where they hope to find something better.

In recent weeks, hundreds of Rohingya refugees have landed on the shores of Indonesia’s Aceh province, including 185 whose boat arrived Jan. 8. At least 180 others are presumed dead, the U.N. refugee agency says, after their boat is believed to have sunk in early December.

More than 3,500 Rohingya refugees in 39 boats tried to cross the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal last year, the agency said last month, compared with 700 the year before. At least 348 of them died or disappeared at sea, making 2022 one of the deadliest years in the last decade.

Calls for maritime authorities in the region to rescue those stranded at sea have been ignored, the agency said, adding that more people will die without a “comprehensive regional response.”

“Inaction from states to save lives results in more human misery and tragedies each day,” said Babar Baloch, the agency’s spokesperson for Asia and the Pacific.

‘Hopeless and dreamless’

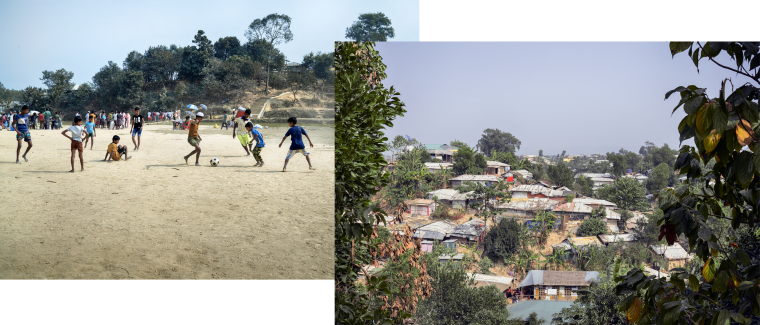

Since August 2017, when the Myanmar military began its attacks on Rohingya civilians, hundreds of thousands have crossed the border into Bangladesh. About 600,000 of them live in Kutupalong, a fenced-in area of about 5 square miles that is now the biggest refugee camp in the world.

A visit to Kutupalong on a Sunday morning in January was typical of most days, with people of all ages gathering at a market to sell vegetables or buy daily necessities. Although Sunday is a school day in majority-Muslim Bangladesh, children played in the dusty streets, in no rush to attend classes that are not obligatory.

Elsewhere, young people sat in roadside shops and chatted, while others collected food rations. Families live in tiny houses made of tarpaulin and bamboo that burn easily during sometimes-deadly fires that sweep through the camp.

The situation at camps like Kutupalong is “getting worse across the board,” said Phil Robertson, the deputy director of the Asia division at Human Rights Watch.

Bangladesh authorities have intensified restrictions on Rohingya refugees’ ability to work, study, worship and travel within the camps, he said, and there is escalating violence from drug gangs, as well as militant groups accused of assassinating community leaders.

There is also police abuse, according to groups like Human Rights Watch, which in January accused Bangladesh’s Armed Police Battalion of “extortion, arbitrary arrests and harassment of Rohingya refugees” since it took over security in Kutupalong and other camps in July 2020. The battalion denies the allegations.

Most Rohingya do not have refugee status in Bangladesh, which cites economic and security concerns, meaning they are deprived of associated rights. Nor do they want to return to Myanmar without full citizenship status and guaranteed protection from the military, which seized power in a coup in February 2021 and denies it has committed atrocities.

“We are becoming mentally sick by thinking of our future and motherland,” said Sayed Ullah, a Rohingya leader in Cox’s Bazar. Feeling “hopeless and dreamless,” he said, Rohingya refugees “are going wherever they can get to.”

Saidul Amin, 22, left for Malaysia in November on the same boat as Hossain, telling his parents the money he earned there could pay for better treatment for their health issues and support the rest of the family. Facing starvation after the engine collapsed, he jumped into the sea, said his father, Jamal Hussain.

“I agreed with my son’s decision to go to Malaysia, but I lost my son,” Hussain, 65, said. “Now I don’t know why I should live.”

Malaysia, a Muslim-majority country, has long been a top destination for Rohingya refugees, some of whom later send for their families to join them. Young women are also transported there to marry Rohingya men whom they may or may not know.

Kutupalong resident Mohammad Majid said his 20-year-old sister, Minara, had left for Malaysia by boat in November to marry her boyfriend.

“It’s been two months, and we don’t know her situation or where she is,” Majid, 30, said. “We are trying to contact our sister, but no one gives us any information.”

Not everyone leaves the camp by choice. Sofura Khatun says traffickers abducted her 14-year-old son, Noor Qader, on his way to school in November.

Two weeks later, she said, her son called her and said, “Mom, save me, they are hitting me. I am being taken to Malaysia by a trawler.”

She said a broker took the phone back and told her he would sell her son unless she paid him $500. Though she complied, she said, she has not had any news since.

“The traffickers didn’t take my child, they took the shelter I cherished for 14 years and my dreams and hopes,” Khatun, 45, said. “How do I get my child back?”

In the short term, Robertson said, it is important for front-line countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand — which, like Bangladesh, are not signatories to the U.N.’s 1951 Refugee Convention — to proactively rescue Rohingya boats, recognize those on board as refugees and work with other countries to support them.

But Robertson and others say Rohingya will continue to take risky boat journeys unless Bangladesh recognizes them as refugees and improves conditions in the camps or Myanmar accepts them back and ends decades of discrimination.

“This will stop once the refugees repatriate to their homeland with full ethnic and citizenship rights and rights to return to their original village,” said Nay San Lwin, a co-founder of the Free Rohingya Coalition, a global network based in Germany. “The international community can make this happen if they are willing to do so.”

At Kutupalong, Hossain’s mother, Rahima Khatun, who is no relation to Sofura Khatun, said she had not wanted him to leave, but “there is no option without escape from here.” They had discussed the possibility, but he left without telling her.

During their video call in early January, Khatun, a 35-year-old widow, sobbed as she asked Hossain repeatedly, “Why did you leave me?” Her three younger children and other relatives were gathered around the phone outside her home.

Hossain told his mother he might be jailed because he had entered Indonesia illegally.

“Since then, we have not talked,” Khatun said in late January. “I only know that he is alive.”