California Democrats have an energized base and a long list of congressional candidates ready to go on Tuesday’s primary day. What could possibly go wrong for them? More than you might think.

After months of state party leaders planning on winning big and capturing long-coveted House seats, Democrats now worry their abundance of 2018 hopefuls combined with the California’s “top-two primary” could freeze them out of some important races. In short, California’s Democrats have met the enemy and, in some districts, they bare a striking resemblance to themselves.

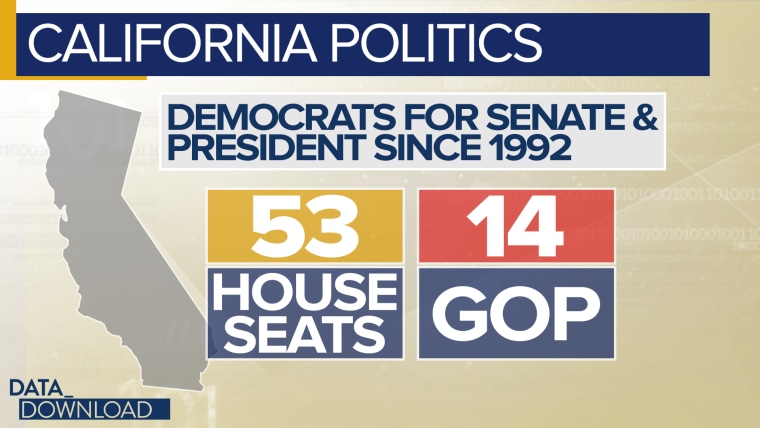

For Republicans, the Democratic quandary is welcome news. The Golden State has not been good territory for Republicans for decades as evidenced by a long string of data points: California has not had a Republican U.S. senator since 1992. It has not voted for a GOP presidential candidate since 1988. And this past week, one analysis found that Republicans were the third largest voting group in the state, behind Democrats and unaffiliated.

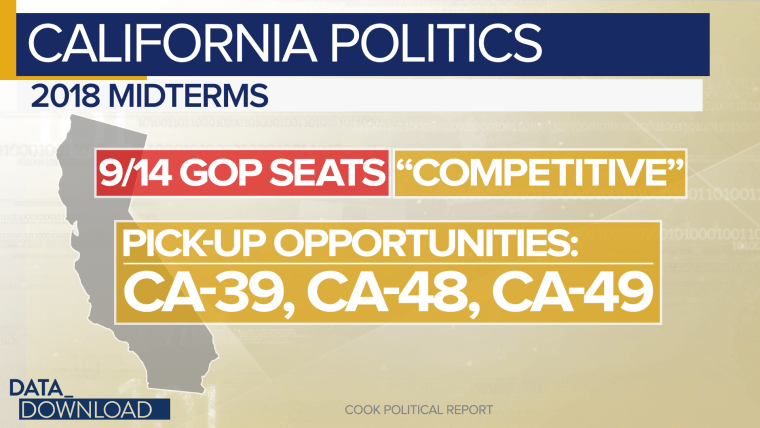

You can see the impact in the state’s House delegation as well. Since the mid-1990s, the number of Republicans it sent to the House of Representatives declined from the mid-20s to only 14 today. Democrats in the state have been eyeing those 14 Republican-held congressional districts and with good reason. The Cook Political Report rates nine of them as competitive – including five it views as tossups.

All of which brings us to the challenges the party faces on Tuesday.

In 2010, the state’s heavily Democratic electorate voted for a ballot proposition that changed the way primaries worked in the state. Instead of primary votes producing Democratic and Republican nominees for the general election, the top-two vote getters would move forward to November regardless of party.

Most people assumed that the net result in heavily-Democratic California would be that many races would feature two Democratic candidates on the general election ballot. And, indeed, that has turned out to the case in some races. It may turn out to the case in the state’s U.S. Senate race where Democratic Sen. Diane Feinstein may wind up facing off against Democratic state Sen. Kevin de Leon in the fall.

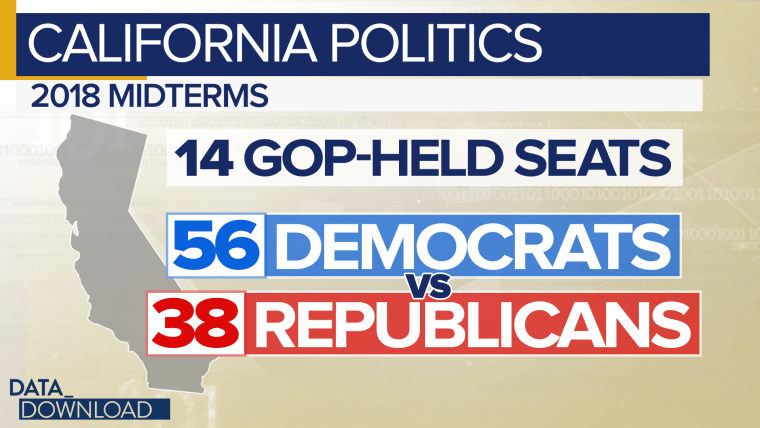

But another possible outcome, particularly in districts where Democrats want to unseat a Republican official, is a rush of candidates that divide the Democratic electorate so diffusely that no candidate makes the top two and the Democrats get frozen out of the general. And when you look at California’s 14 GOP-held House districts, there are some real reasons for the Democrats to fear that outcome.

In those 14 districts, there is an average of almost eight candidates per race, with a total of 56 Democrats running in them.

That’s an average of four Democrats per district. And even if a district is, say, 60 percent Democratic, when you split that 60 percent four ways you end up with some small numbers.

As a contrast, the other 39 districts currently held by Democrats have an average of only 3.5 candidates per race. A total of 59 Democrats are running in them, on average less than two per contest.

There are a few districts in particular that worry the Democrats. Consider the 39th, 48th and 49th, all of which are currently rated as toss-ups. The 39th has six democratic candidates. The 48th has eight. The 49th has only four, but they all appear to be viable and none has a special edge on the others. That’s a lot of potential splits in the Democratic vote in districts that most recently elected a Republican.

And the three districts have some symbolic meaning for the Democrats because of where they are located. Each holds at least some of Orange County, once a Republican stronghold that has slowly drifted Democratic. Orange voted for a Democrat in the 2016 presidential race, Hillary Clinton, for the first time since 1936.

Democrats would love to win those three seats to show the political change is deeper than 2016 and that it is extending to other races. But for that to happen, the Democrats are going to have to get over their first hurdle Tuesday, themselves.