News analysis

WASHINGTON — White House press secretary Sarah Sanders added a new level of uncertainty over the future of Robert Mueller when she seemed to suggest Tuesday that the president might have the power to fire the special counsel.

"I know a number of individuals in the legal community and including at the Department of Justice that he has the power to do so," she said, though it was not clear whether she might have meant that the president could direct the deputy attorney general to fire Mueller.

But does the president have the authority to do it himself?

There's no clear answer, and there is apparently no formal opinion from the Justice Department concluding that the president has that power.

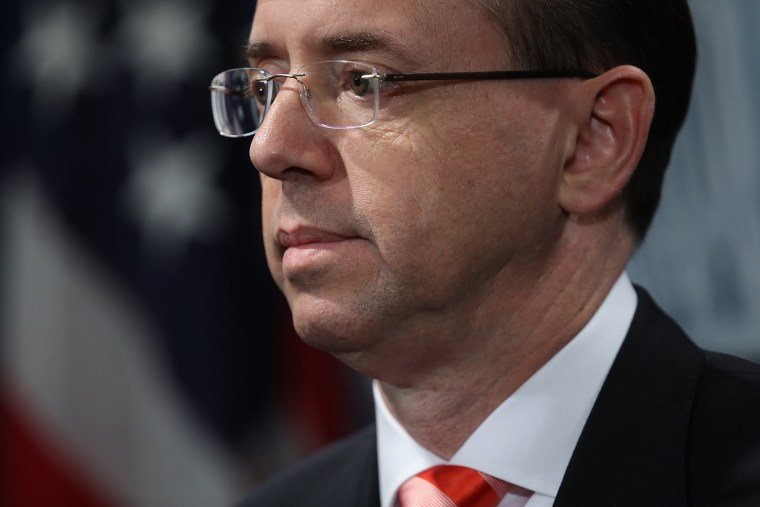

Under the Justice Department regulations that set up the office of special counsel, Mueller can be fired only by Rod Rosenstein, who is overseeing the special counsel's investigation.

Normally, this power rests with the attorney general, but Jeff Sessions has recused himself, so it falls to Rosenstein. The regulations say a special counsel can be fired "for misconduct, dereliction of duty, incapacity, conflict of interest, or for other good cause, including violation of Departmental policies."

These regulations also say a special counsel "may be disciplined or removed from office only by the personal action of the Attorney General" (in this case, the deputy attorney general).

That would seem to mean that only Rosenstein could fire Mueller.

But there's a potential constitutional issue — namely that a president, as chief executive, has the authority to fire anyone in the executive branch. According to this argument, such a constitutional power would override any statute or regulation.

And some legal scholars have suggested another scenario: Trump could argue that Mueller is interfering with foreign relations and that the president therefore had separate authority to fire him.

Legal experts, as they often do, disagree about what Trump could do, and the courts have never provided an answer to a situation like this.

Rosenstein has repeatedly said he has confidence in Mueller and sees no grounds for firing the special counsel. If Trump ordered Rosenstein to do it anyway and Rosenstein refused, Trump would clearly have authority to fire the deputy attorney general.

Under an executive order spelling out the order of succession at the Justice Department, authority over Mueller would then fall to the associate attorney general, who was Rachel Brand. No successor to her has yet been confirmed.

So authority would then go to U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco, a longtime Washington lawyer and Trump appointee. From there, it falls to U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, although that position is currently held by an acting official, then to the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of North Carolina, Robert Higdon, and then to the U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Texas, Erin Nealy Cox.

Of course, any move to fire Mueller, either directly or indirectly, would have serious political consequences for the president.

"Trump has all sorts of powers," said Neal Katyal, a former acting solicitor general in the Obama administration. "That doesn't mean exercising them is wise or comports with the rule of law. If he fires Mueller or Rosenstein to protect himself, it is an impeachable offense and will trigger a constitutional crisis."

And firing the special counsel would not accomplish Trump's goal of putting an end to the Russia meddling investigation. The probe would simply revert to the FBI and the Justice Department, where prosecutors and federal agents would continue the kind of work they were doing before the special counsel was appointed.