RICHMOND, Va. — Dean Turner never voted before he went to prison. But his right to cast a ballot was the last barrier to rebuilding his life once he got out.

Released in February 2016, after more than a decade behind bars for selling drugs, the 50-year-old Virginian worked his way up from dishwasher to line chef by Googling how to cook. He started mentoring young men, and coaches a writing class at Virginia Commonwealth University based on the book he helped write while incarcerated. But until last fall, Turner was one of the estimated 6.1 million Americans — 2.5 percent of the nation’s voting-age population — barred from voting by a felony conviction.

"When you’re able to vote, that means you have a voice in the world," Turner told NBC News. Former Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a Democrat, restored his voting rights last year, and Turner cast his first-ever ballot in November 2017.

“It was the best feeling,” he said. “That was the little stamp of approval that I turned myself around, I’m a citizen of society.”

Virginia isn't the only state with a recent push to restore voting rights to ex-offenders. Alabama, Wyoming and Maryland have also begun easing voting restrictions for released felons, while Florida organizers announced Tuesday that they had succeeded in gathering enough signatures for a ballot initiative this November that would rewrite the state’s permanent felon voting ban and give an estimated 1.5 million ex-offenders the vote.

Nearly every state has laws to prevent people convicted of a felony — a crime more serious than a misdemeanor — from voting, though policies vary. Some 14 states disenfranchise felons while in prison, and another 22 disenfranchise during post-release periods like probation and parole as well, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

But Virginia is one of 12 states that bars ex-offenders from voting even after their sentences are complete. In order for ballot access to be restored, these states require waiting periods, an application process, or action from the state's governor. McAuliffe used his executive authority to individually reinstate voting rights to some 173,000 ex-offenders, including Turner, before leaving office in January.

“They’re out, they pay taxes, they’re back in society, they should be able to vote,” McAuliffe told NBC News. “I was only doing what I thought was right.”

But that was just a Band-Aid for what's both a moral and civil right problem, he said. Because the U.S. criminal justice system disproportionately incarcerates people of color — African-Americans are incarcerated at a rate five times that of whites — this translates to a disproportionate numbers of minorities unable to vote. Advocates say the time to revisit felon voting bans is long overdue.

Conservative critics, however, argue for a more cautious system, where ex-offenders must prove themselves.

“If you’re not willing to follow the law, you shouldn’t have a role in making the law for everyone else,” said Roger Clegg, president and general counsel of the Center for Equal Opportunity, a conservative think tank that opposes affirmative action. “I don’t think that’s that unreasonable given the fact that recidivism rates are so high."

Florida ex-offenders fight for "second chances"

When Desmond Meade’s wife ran for a seat in Florida’s State House in the 2016 election, he knocked on doors and helped her campaign. But three felony convictions, acquired during years of drug addiction, kept him from voting for her.

Meade, 50, applied for clemency, Florida's process for restoring voting rights to released felons, but was rejected because it was too soon after his release.

According to The Sentencing Project, a D.C.-based group that advocates for criminal justice reform with the aim of reducing the incarceration rate, 10 percent of Floridians couldn't vote in 2016 due to felony convictions. That number is even higher within the state's black population — 21 percent of African-Americans are barred from the ballot box.

Florida doesn't track how many clemency applicants are rejected, but during the last six years under Republican Gov. Rick Scott, just 2,898 ex-offenders' rights had been restored as of early December, with 10,264 applications pending.

Applicants must wait five to seven years depending on their crime before applying, and hearing back from the board can take years after that. Many ex-offenders then appear in person to appeal to the governor and the other members of Executive Clemency Board in person.

“Do I sit around and wait for ten years and roll the dice and see whether or not they want to restore my rights? Or do we change a broken system?” Meade said. “I chose to spend my energy fixing a broken system.”

Meade got enough signatures to get a ballot initiative proposed and approved by the state Supreme Court that would restore voting rights to people with felony convictions upon completion of their sentences, including parole and probation. Then, he and his group, Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, gathered more than 800,000 signatures to put it on November's ballot. The American Civil Liberties Union, who said they’ll spend at least $5 million in support, and the Florida League of Women Voters, threw some muscle behind the campaign.

A spokesman for the Florida governor told NBC News in an email that Scott "has been clear that the most important thing to him is that felons can show that they can lead a life free of crime and be accountable to their victims and our communities." She noted that the ballot initiative, which needs 60 percent of votes to pass and amend the law, is "a decision for each voter to decide on."

Richard Harrison, a Tampa attorney, launched Floridians for a Sensible Voting Rights Policy to oppose the ballot initiative. He told NBC News he doesn’t support a broad restoration of rights, but rather an application process that evaluates individual cases. The amendment, which excludes people convicted of murder or a felony sexual offense, would still restore rights to “all sorts of violent criminals,” he said.

Harrison, who said he is a registered Republican, said he personally worries the amendment could create an army of new Democratic voters and said he was surprised Republicans haven’t been more vocal.

“In a state where Trump only beat Clinton in the election by less than 113,000 votes across the state, that’s a lot of potential swing,” he said of the 1.5 million disenfranchised ex-offenders. “It’s Florida, everything is political, of course.”

"I’m living testimony"

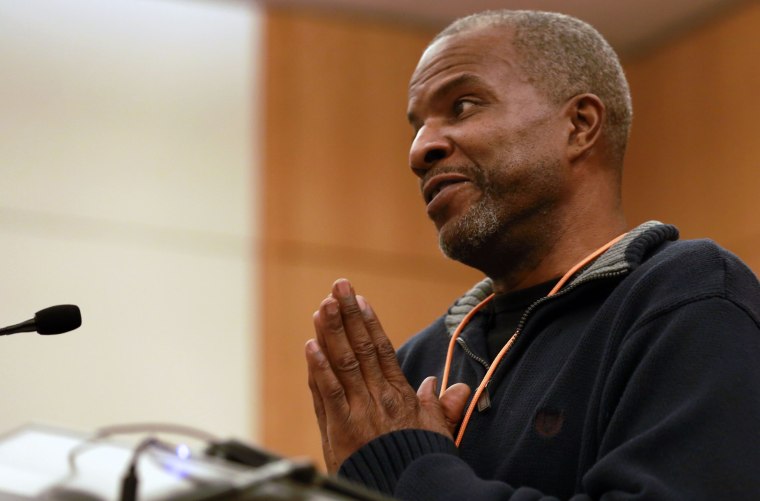

Christopher Green, 58, registered to vote the day after he got a letter in the mail saying McAuliffe had restored his rights. He spent 15 years in and out of prison, but now works as a community organizer for New Virginia Majority — one of the progressive activist groups that supported the governor's efforts.

“It’s empowering, for someone like me who has struggled for so many years with drug addiction and crime,” he told NBC News. “I felt like I could tackle the world.”

Green cast his first-ever ballot in the 2016 presidential election. Last year, he helped Turner, the line chef, register to vote.

“I’m living testimony, like when I do go into the community I can tell people: Your vote does matter, what you say does matter,” he told NBC News, standing outside a subcommittee room of Virginia's House of Delegates. He had just spoken to lawmakers about a bill that would help acquitted Virginians get their records expunged. It failed, but he wasn't deterred.

“I can say that because I’ve experienced that," Green said. "I have been down here, we’ve defeated bills, we’ve weighed in on bills, we’ve changed people’s minds.”