WASHINGTON — Democrats believe they have more than a smoking gun in President Donald Trump's impeachment trial. They have a trigger man, they have a motive and they have a record of the key moment.

What they would like more of — but do not believe would be necessary in a jury trial — is access to documents they know exist and witnesses close to Trump whom they believe would further support the case for removing him from office.

"This is airtight," said a person familiar with the prosecution, who noted that all of the witness testimony obtained during the House investigation corroborated a long campaign by top Trump lieutenants to effect the president's Ukraine plan. "What [we] don't have is someone saying, 'I helped orchestrate that monthslong effort.'"

So as House managers wrapped up their three-day presentation in Trump's Senate impeachment trial Friday and prepared to watch his defense counsel mount a counteroffensive, they tried to leave no reasonable doubt that the president worked to corrupt Ukraine's new president by using $391 million in funds already appropriated by Congress to force him to open investigations that would help Trump's re-election campaign.

But Democrats were still hoping against hope they could get more witnesses — and that either Republican senators would be persuaded that refusing to oust Trump would damage the country, or voters would be persuaded that Republicans should be punished for failing to remove him.

That, of course, was framed in terms of country over party.

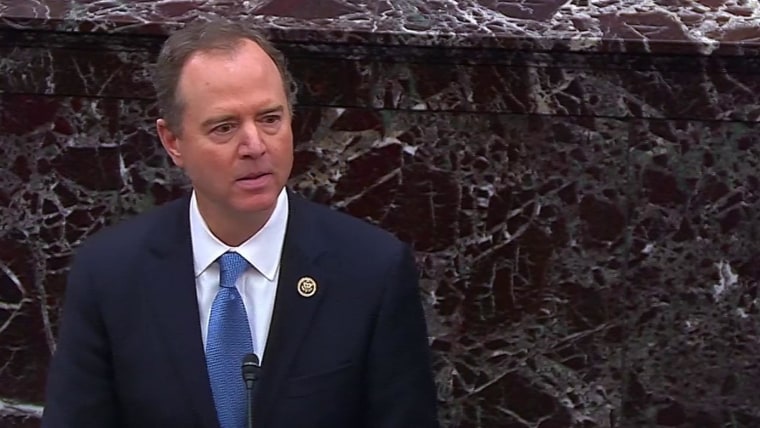

"We must not become numb to foreign interference in our elections," Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., the lead House prosecutor said. "Our elections are sacred."

He argued that Trump represents an ongoing threat to the republic because he has boasted about welcoming foreign engagement in U.S. elections so long as it benefits him and has failed to take seriously Russia's continuing efforts to tamper with American politics. And Schiff said that if Congress does not respond to Trump's actions — and the threat he poses — he will leave the U.S. without real allies abroad and with a domestic population cynical about the "free and fair elections" that have been a hallmark of the republic.

"Let's say they start to blatantly interfere in our election again to help Donald Trump," Schiff said of Russia or other foreign nations. "Can you have the least bit of confidence that Donald Trump will stand up to them and protect our national interest over his own personal interest? You know you can't, which makes him dangerous to this country."

The weaknesses of the case can be found in the political strength of a president whose fellow Republicans are expected to vote nearly or fully in lockstep to keep him in office, regardless of what they think of his actions — a handful will say they were imperfect, and others will say they see nothing wrong with what he did — and in his ability to use executive fiat to prevent prosecutors from obtaining evidence from his closest circle of advisers and documents housed at various federal agencies.

And as Kim Wehle, a former assistant U.S. attorney and author of the book "How to Read the Constitution and Why" noted, Democrats didn't use all of the tools at their disposal to get information.

"House Democrats didn't subpoena all the witnesses who have relevant information — some of the closest people to the president, like John Bolton — or move to compel compliance," she said, referring to the former national security adviser. "Trump had no legal basis for withholding all information completely, but rules mean nothing without enforcement. Their failure to push for information in the House gives political cover for Senate Republicans to vote down more witnesses, and ultimately provide an excuse to acquit on the rationale that Democrats admittedly didn't do enough to prove their case."

Because Trump blocked access to witnesses and documents that could clarify what roles he and his senior aides played, they have impeached him for obstructing Congress in addition to abusing the powers of his office.

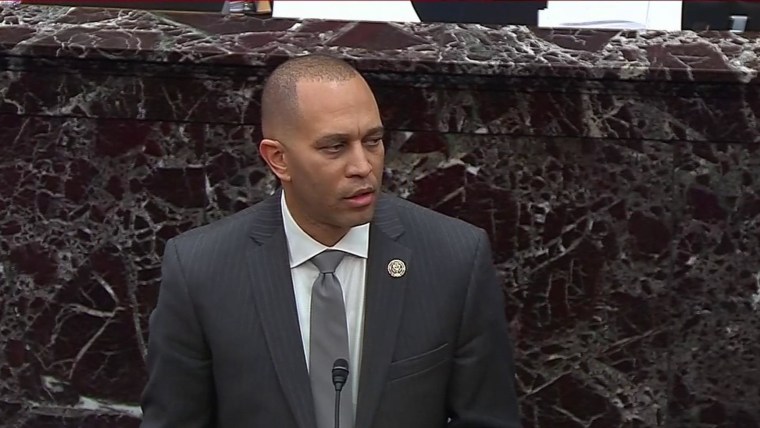

"President Trump tried to cheat, he got caught and then he worked hard to cover it up," said Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, D-N.Y., one of the House managers.

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., a former harsh Trump critic turned leading defender, said Friday that the president's defense team should be concise in its rebuttal and try to "poke holes" in the prosecution's case. From the president's defenses so far, there is not a comprehensive alternative theory for his actions or a set of facts that contradict those laid out by prosecutors.

Neither Trump nor his lawyers have said that his personal attorney Rudy Giuliani did not plan to go to Ukraine in May to meet with newly elected Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy in order to seek investigations into former Vice President Joe Biden and a Russia-originated disinformation campaign designed to obscure Moscow's role in helping Trump in the 2016 election. That shows the motive.

Trump has contended that his call with Zelenskiy on July 25 — the record of Trump as the trigger man — was "perfect."

There were four topics discussed on the call: U.S. aid for Ukraine, a White House meeting between Zelenskiy and Trump, the Biden investigation, and the "Crowdstrike" probe. As any member of Congress might attest, such meetings between elected leaders invariably involve "asks" in which the officials exchange favors. Before and after the call, aides to both presidents did significant legwork to set them up to discuss the items under discussion and then execute the quid pro quo, as evidence produced in the House investigation showed.

All of that is normal business — unless the trade is corrupt.

U.S. officials said in testimony that they were shocked to find Trump brazenly dangling already appropriated funding and a White House meeting before Zelinsky's eyes for investigations into one of his leading political opponents, and a conspiracy theory that would muddy the truth that Russia had assisted his first victory. At the time, Trump's decision to pause the flow of U.S. aid to Ukraine while he was pursuing the probes was kept to a tight circle, but it would become more widely known over the ensuing months.

Members of Congress know that leveraging taxpayer dollars to solicit foreign help in an election is inherently corrupt, and the strength of Democrats' case is that counterarguments require radical suspensions of disbelief — like accepting that Trump froze the aid but not to put pressure on Kyiv, sought an investigation into his leading political rival but not because of the electoral implications, and didn't publicly call for other countries to probe that rival and his family — as well as neglect of powerful evidence to the contrary.

"It's virtually impossible to deny that Trump took actions for his own benefit, and not for the good of the American people," Wehle said. "Indeed, Republicans aren't even arguing that he did what's best for the U.S."

But each senator sets his or her own standard in an impeachment trial.

"I think he has a style of working and negotiating," Sen. Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, said when NBC's Leigh Ann Caldwell asked whether what Trump had done was wrong. "Is it an impeachable unlawful offense? That has not been clearly demonstrated."