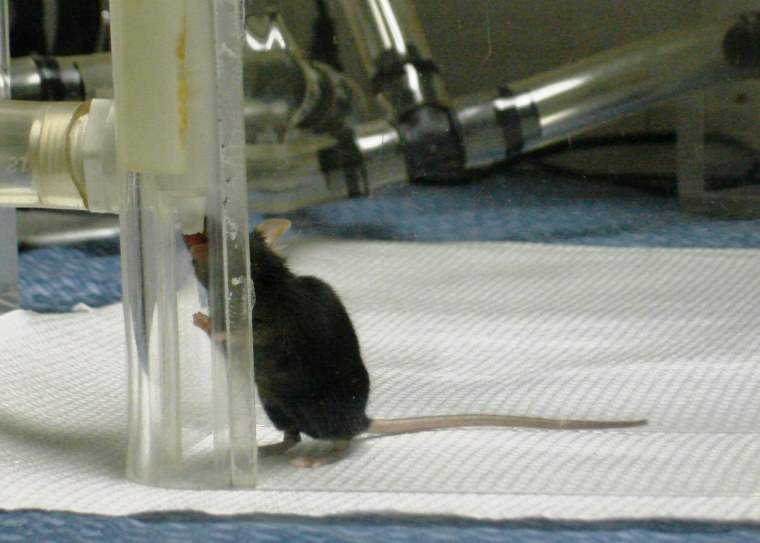

Scientists have trained mice to recognize the whiff of bird flu in duck poop, and they think they can train dogs to do the same thing. If so, flu-sniffing dogs -- or chemical sensors built to duplicate this not-so-stupid pet trick -- could become a new line of defense in the fight against epidemics. The latest findings focus on the detection of avian influenza, a.k.a. bird flu. But Bruce Kimball, a U.S. Department of Agriculture researcher who presented the study today in Boston at a meeting of the American Chemical Society, suggested that the trick could be used to sniff out other diseases as well. "To be honest with you, I think we could demonstrate this type of effect in a lot of areas," he told me. Early-warning systems for illness in animal populations are important for human health as well. Species-jumping diseases can pose a deadly threat to all of us, as we saw with bird flu and H1N1 flu (a.k.a. swine flu). Developing new tools for identifying such infectious diseases is one of the scientific missions of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, where Kimball does his work. The studies of poop-smelling mice involve researchers from Monell as well as various agencies within USDA. Kimball and his colleagues haven't yet figured out exactly what sets of the flu alarm in mice. The trigger is probably a suite of volatile chemicals rather than just one chemical ingredient. And it probably has more to do with chemicals released as part of the ducks' immune response rather than the influenza virus itself. But whatever those mice are smelling, it seems to correlate strongly with the disease. "I always like to joke that we're going to send people out with mice on leashes," Kimball told reporters during a webcast news briefing. It's far more likely, however, that the job would be given to other animals with a keen sense of smell -- perhaps the same breeds of dogs that are so good at sniffing out drugs or cadavers. "We're also holding out hope that one day we can be as good as mice or dogs in detecting things from the volatiles," using gas chromatographs instead of animal noses, Kimball said. Here's how the mice were trained: Samples of feces were collected under laboratory conditions from healthy as well as flu-infected ducks at Colorado State University. Then six mice were trained as poop-sniffers in a Y-shaped maze. If a mouse went toward the virus-laden sample, it won a reward: a sip of water to ease its lab-induced thirst. If it went toward the healthy sample, no reward. It took hundreds of trials, but eventually the mice became good at identifying the feces from the infected ducks. More than 90 percent good. To test their skill, the four-footed "biosensors" were presented with pairs of healthy-vs.-infected samples they hadn't previously sniffed, in a double-blind situation where not even the people running the experiment knew at the time which was which. No rewards were doled out, and yet the mice still made the right choice 77 percent of the time (65 out of 84 trials). "We're trying to replicate that, using chemical instrumentation as the nose instead of the mouse," Kimball said. "The mouse is much better right now. ... We have no idea, really, how the mice are processing all that data, so we're just taking our best stab at using mathematics to use the same thing." The researchers are anxious to identify the factors behind the mice's impressive performance so they can be sure that the sniff method will work outside the laboratory. There are still a couple of questions to be addressed: For example, all the poop samples were irradiated during the experiment to kill off the virus, for safety's sake. Now Kimball and his colleagues will have to verify that the irradiation process didn't alter the scents in the virus-laden samples to make them stand out. The researchers also aren't completely sure whether the mouse trick can be carried over to mutts or machines. "We're not prepared to go with the dog system yet," Kimball said. But he hopes that flu-sniffing dogs could someday be taken to, say, a chicken coop in Indonesia and sniff out whether birds in the flock are infected. That could "provide us with an early warning about the emergence and spread of flu viruses," he said in a news release about the research. And the warning signs might not be just in bird poop: Kimball referred to previous research indicating that the presence of mouse mammary tumor virus altered the body odor of mice, even before a tumor could be detected. Other experiments suggest that vaccinated mice have the special odor as well. He said it's "very logical" that the scent of a virus -- or, more likely, the scent of an immune response -- could waft from the skin as well as from the feces. "It is very possible that a whole body profile could tell us the same thing," Kimball said. Which would make future studies a whole lot more pleasant. Collecting poop from diseased ducks has to rank as one of the worst jobs in science. More on poop in science:

- Your poop is like a fingerprint

- These dogs have a nose for doo-doo

- Chinchilla poop reveals how much it rained

- Human hairs found in prehistoric hyena poop

Join the Cosmic Log corps by signing up as my Facebook friend or hooking up on Twitter. And if you really want to be friendly, ask me about "The Case for Pluto."