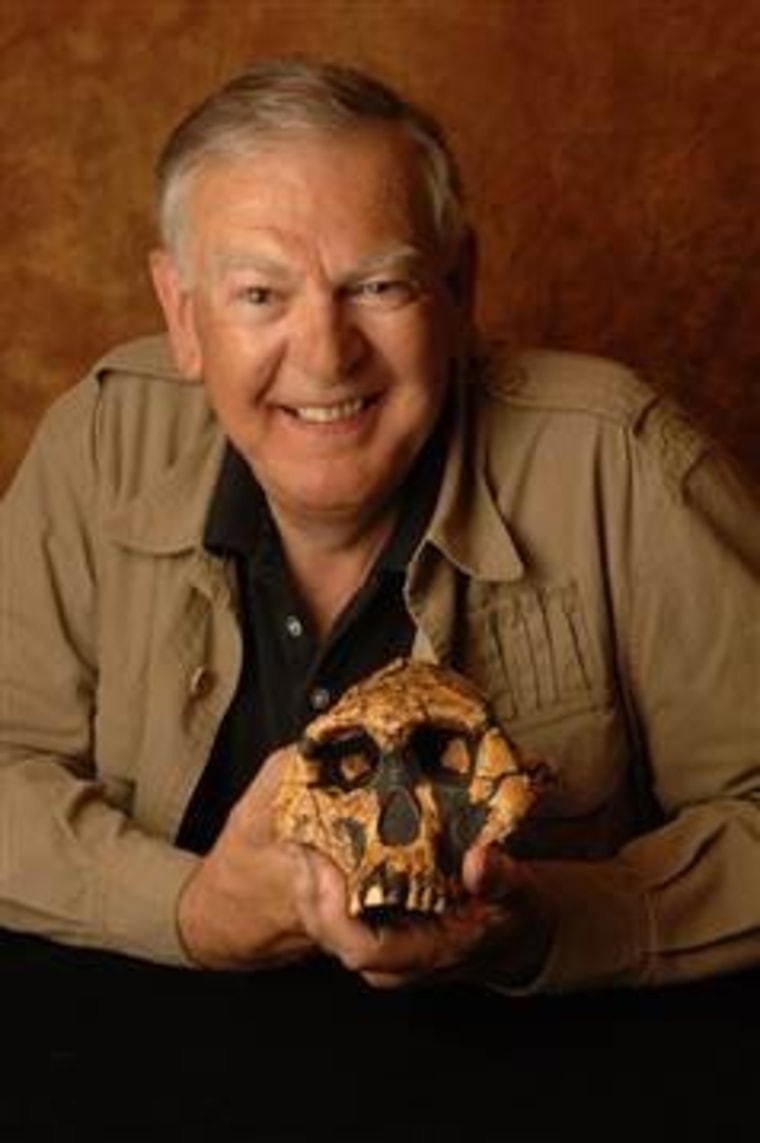

The discoverer of the famous "Lucy" fossil says fresh findings suggest that more than one ancient species made the transition to more humanlike forms in different parts of Africa.

Arizona State University paleoanthropologist Don Johanson shook up the scientific world in 1974 when he came across the traces of a 3.2 million-year-old skeleton in Ethiopia, a pre-human ancestor that came to be called Lucy. A similar shake-up may well be in the works due to the detailed analysis of another set of 1.977 million-year-old bones found in South Africa.

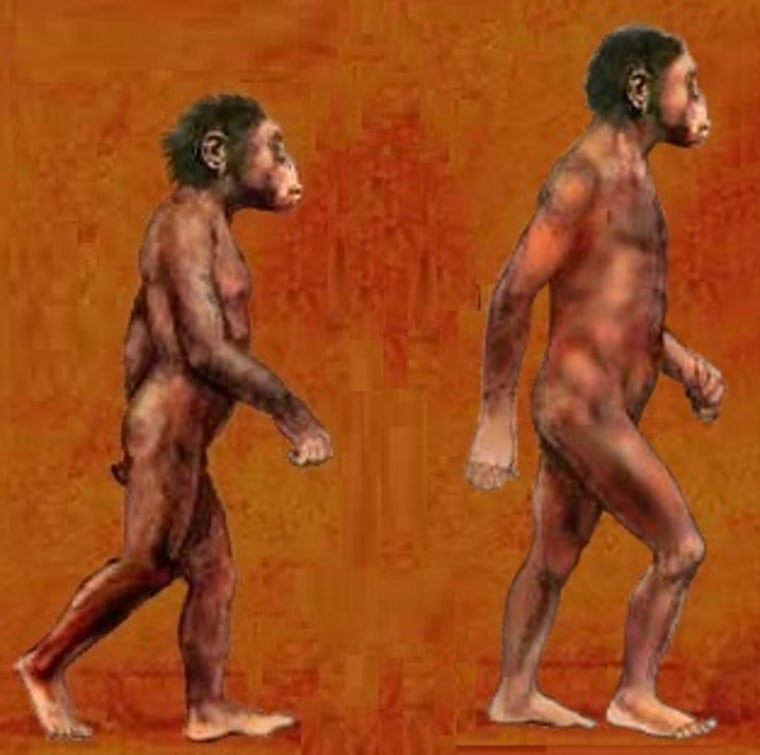

In a series of studies published this week in the journal Science, researchers make a strong case that the bones, ascribed to a species called Australopithecus sediba, illustrate how the bodies of humanlike primates became more suited for upright walking, tool-making — and bigger brains.

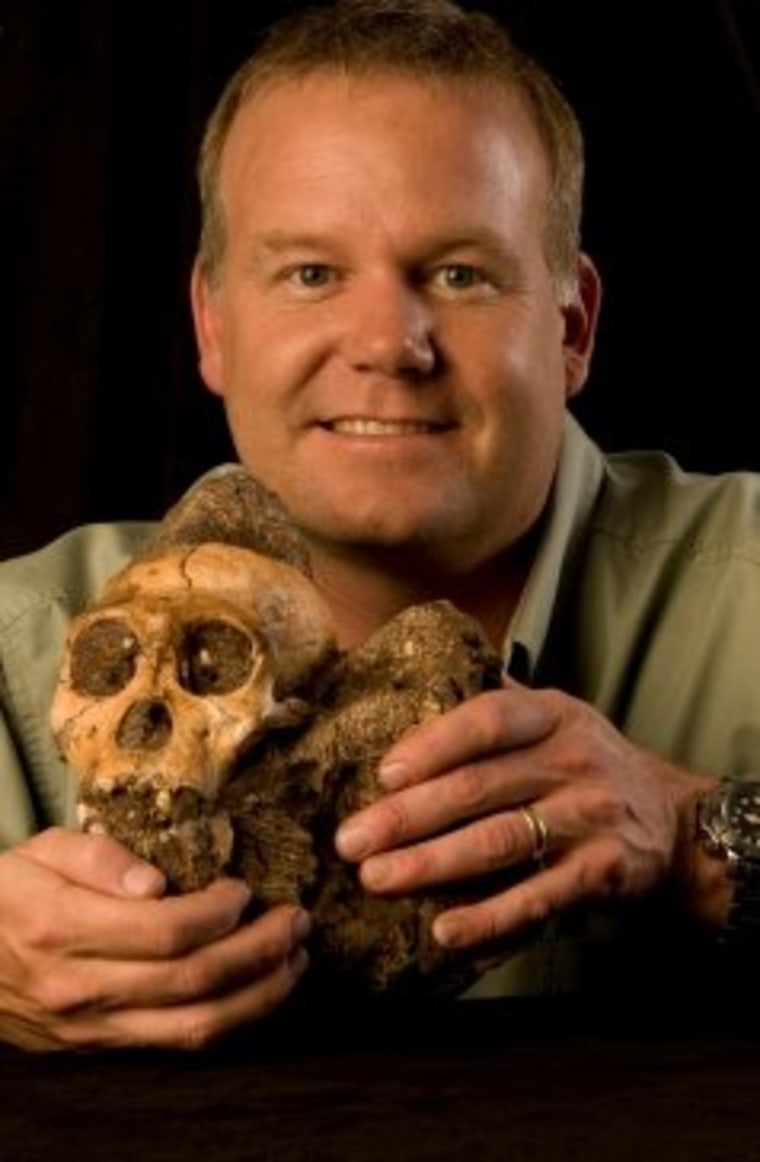

The international research team, led by the University of Witwatersrand's Lee Berger, says A. sediba is a good representative of the type of creature leading to the emergence of the genus Homo, which includes us Homo sapiens types as well as Neanderthals and a host of other now-extinct species.

But Johanson told me today that few of the reports about the latest findings touch on "the real crux of the matter." Even though A. sediba is a transitional form, with features of Australopithecus as well as Homo, he said there are other specimens of the genus Homo in eastern Africa that have been dated to roughly the same time. "There is a diversity of Homo already at 1.8 million years," he said.

In fact, at least one of the fossil bones traditionally ascribed to Homo — an upper jaw from the same area of Ethiopia where Lucy was found — has been dated to an age of 2.3 million years, Johanson said. He sees that as a sign that some primates in east Africa had completed the transition to Homo while others in southern Africa were still in the midst of that transition.

"Right after 3 million years toward the present, we see that there is a response in eastern and southern Africa which are on two different evolutionary trajectories," Johanson said. One trajectory led to grass-eaters such as Paranthropus robustus and Paranthropus boisei, and the other trajectory led to bigger-brained species such as Homo ergaster, Homo rudolfensis and Homo habilis. He said Homo habilis appears to have existed in east Africa at the same time that australopiths in southern Africa were becoming more Homo-like.

"For the very first time, we've found the roots of Homo in south Africa, but it's too late to be the roots of Homo in east Africa," Johanson said.

During a teleconference, Berger said it can be difficult to tease out the relationships between the various species along the evolutionary path leading to modern humans.

"We're dealing with a period between, say, 2.3 million years and 1.6 milion years where the entire remainder of the fossil record could fit into a small shoebox, as opposed to these very well-preserved skeletons," Berger said. But he insisted that A. sediba "may very well be as good a model or better than the Homo habilis one, which actually only has a larger brain to go with it." He pointed out that our knowledge about Homo habilis was based on "very fragmentary fossils."

Darryl de Ruiter, an anthropologist at Texas A&M University who is part of Berger's team, said researchers considered whether A. sediba represented nothing more than an evolutionary dead end. "But as we pointed out, and as all these papers are demonstrating, in every aspect of the skeleton — cranium, teeth, jaw, mandibles, hand, pelvis, foot, everything that we look at — we see characteristics that align this species more closely with Homo than any other australopith," he said.

When the discovery of the A. sediba fossils was announced last year, Johanson speculated that the species might be more appropriately considered a part of the genus Homo than the genus Australopithecus. "I've actually changed my view," Johanson said. Now he agrees with Berger's team that it's an australopith. And who knows? Anthropologists may well change their minds many times as more fossils come to light.

In any case, Johanson said, this week's revelations are "very, very interesting."

"It does show that there are probably different ways of being an upright walker, and there are different ways of arranging the anatomy," he said. "There isn't just one strict way."

More about human evolution:

- Humans had sex with now-extinct relatives

- Fossils suggest Lucy's species used stone tools

- Lessons still being learned from Lucy

- Search for human evolution on msnbc.com

Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the log's Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter or adding me to your Google+ circle. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for other worlds.