A new type of living battery has been created that generates electricity from dissolved organic matter such as that found in wastewater flushed down the toilet or washed off farms and out to sea.

The system is as efficient as the highest performing solar cells and, in theory, could generate as much energy as is needed to treat wastewater with current technology, according to researchers working on the so-called microbial battery at Stanford University in California.

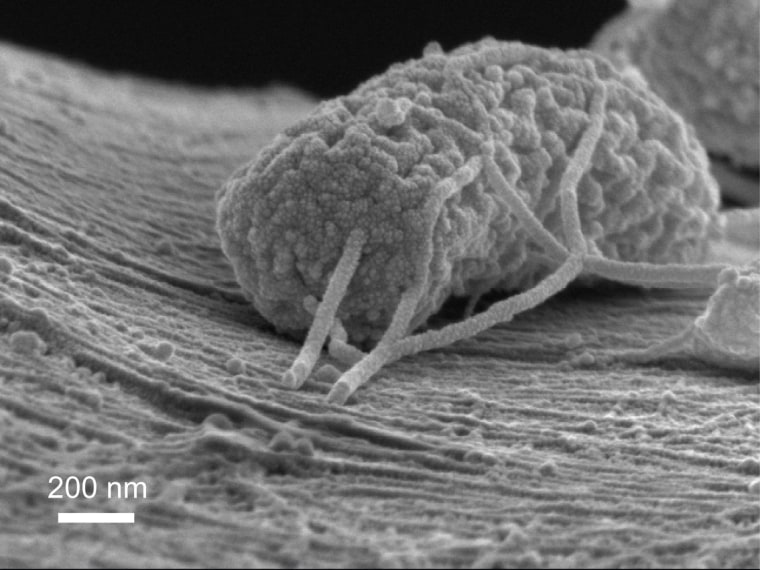

The new technology hinges on naturally occurring microorganisms that feast on plant and animal waste for their own biological fuel. Once wired up, the tiny creatures essentially poop out electrons that can be harnessed for an electric current.

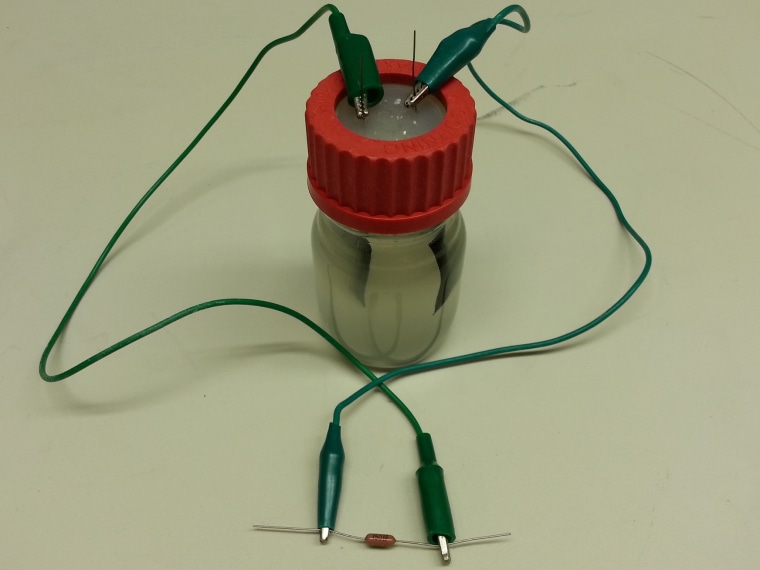

In the prototype design described today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the feasting microbes latch themselves onto carbon filaments. Their excreted electrons flow from the filaments to a positive electrode made of silver oxide, a material that attracts electrons.

"We call it fishing for electrons," Craig Criddle, an environmental engineer at Stanford University in California and a paper co-author, told NBC News. "We are really fishing for electrons from that organic matter."

En route to the silver oxide, the electrons travel to an "external circuit where they could be used to, say, charge up batteries for human use," he explained.

The electrons then flow back to the other electrode — the silver oxide — which they reduce to silver via a chemical reaction.

When a full load of electrons is absorbed, the silver oxide becomes a chunk of silver and the electric current stops. To recharge the battery, the electrode — the chunk of silver — is removed from the battery and oxidized, which releases the electrons.

"When we stick it back in the battery, we can continue to harvest electrons," Criddle explained. "It is ready; it is baited now and ready to fish for electrons again."

The team estimates the technology can harvest about 30 percent of the potential energy locked in wastewater.

However, the battery relies on such an expensive material — silver oxide — that it is unlikely to "result in an economically feasible technology that can be implemented to produce electricity," Abhijeet Borole, a bioscientist at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory, told NBC News in an email.

The elegance of the microbial battery, according to the Stanford team, is its rather simple design. The electrode removal and recharging steps, however, cause further setbacks, as they require "additional chemicals and additional electricity to enable energy harvesting from waste," noted Borole, who was not involved in the new research.

What's more, he added, the "presence of contaminants in wastewater (sulfide, etc.) may poison the silve/silver oxide electrode and reduce its efficiency or make it dysfunctional."

Criddle understands the limitations of the technology. Going forward, he said, "We want to get cheap materials that accept electrons."

The group has identified several candidates and is conducting experiments to determine if they will work. Once an alternative is found, they hope to scale up the technology for commercial production.

John Roach is a contributing writer for NBC News. To learn more about him, visit his website.