The second hydrogen explosion in three days rocked Japan's stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant Monday, sending a massive column of smoke into the air and wounding six workers. It was not immediately clear how much — if any — radiation had been released.

The explosion at the plant's Unit 3, which authorities have been frantically trying to cool following a system failure in the wake of a massive earthquake and tsunami, triggered an order for hundreds of people to stay indoors, said Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano.

The blast follows a similar explosion Saturday that took place at the plant's Unit 1, which injured four workers and caused mass-evacuations. More than 180,000 people have evacuated the area, and up to 160 may have been exposed to radiation.

Japan's nuclear safety agency said six workers were injured in Monday's explosion but it was not immediately clear how, or whether they were exposed to radiation. They were all conscious, said the agency's Ryohei Shomi.

The reactor's inner containment vessel holding nuclear rods was intact, Edano said, allaying some fears of the risk to the environment and public. TV footage of the building housing the reactor appeared to show similar damage to Monday's blast, with outer walls shorn off, leaving only a skeletal frame.

Tokyo Electric Power Co. said radiation levels at plant were 10.65 microsieverts Monday afternoon, significantly under the 500 microsieverts at which a nuclear operator is legally bound to file a report to the government.

But Pentagon officials reported Sunday that helicopters flying 60 miles from the plant picked up small amounts of radioactive particulates — still being analyzed, but presumed to include cesium-137 and iodine-121 — suggesting widening environmental contamination, .

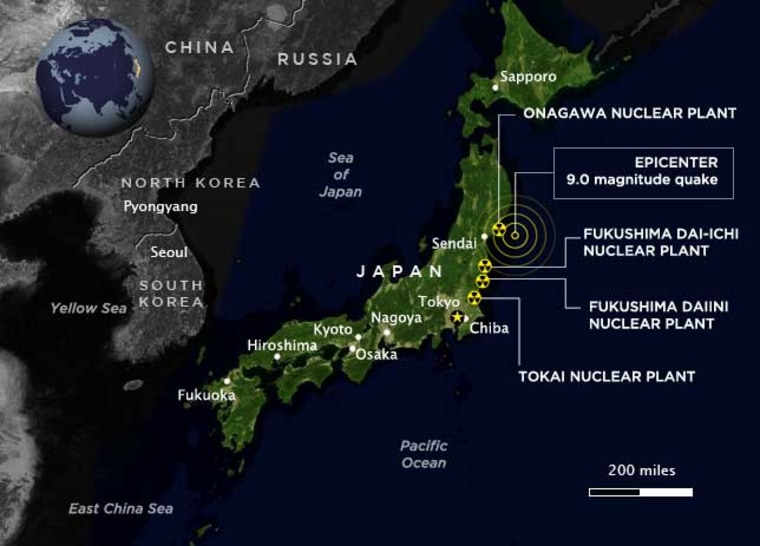

A massive column of smoke was seen belching from the Fukushima Daiichi plant's No. 3 unit Monday. Four nuclear plants in northeastern Japan have reported damage.

Operators have been dumping seawater into units 1 and 3 in a last-ditch measure to cool the reactors. They were getting water into the other four reactors with cooling problems without resorting to corrosive sea water, which likely makes the reactors unusable.

A meltdown at the No. 3 reactor could be more serious than at the other reactors because it is fueled by both plutonium and uranium, . The others have only uranium fuel.

Earlier, Edano said radioactivity released into the environment so far was so small it didn't pose any health threats.

Such statements, though, did little to ease public worries. In a country where memories of a nuclear horror of a different sort during the last days of World War II weigh on the national psyche and national politics, the impact of continued venting of long-lasting radioactivity from the plants is hard to overstate, the New York Times reported.

"First I was worried about the quake," said Kenji Koshiba, a construction worker who lives near the plant. "Now I'm worried about radiation." He spoke at an emergency center in Koriyama, about 40 miles (60 kilometers) from the most troubled reactors and 125 miles (190 kilometers) north of Tokyo.

At the makeshift center set up in a gym, a steady flow of people — mostly the elderly, schoolchildren and families with babies — were met by officials wearing helmets, surgical masks and goggles.

About 1,500 people had been scanned for radiation exposure, officials said.

Up to 160 people, including 60 elderly patients and medical staff who had been waiting for evacuation in the nearby town of Futabe, and 100 others evacuating by bus, might have been exposed to radiation, said Ryo Miyake, a spokesman from Japan's nuclear agency. It was unclear whether any cases of exposure had reached dangerous levels.

A foreign ministry official briefing reporters said radiation levels outside the Daiichi plant briefly rose above legal limits, but had since declined significantly.

Edano said none of the Fukushima Daiichi reactors was near the point of complete meltdown, and he was confident of escaping the worst scenarios.

Officials, though, have declared states of emergency at the six reactors where cooling systems were down — three at Daiichi and three at the nearby Fukushima Daini complex.

The U.N. nuclear agency said a state of emergency was also declared Sunday at another complex, the Onagawa power plant, after higher-than-permitted levels of radiation were measured there. But radiation levels at that plant returned to normal later Sunday.

A pump for the cooling system at yet another nuclear complex, the Tokai Daini plant, also failed after Friday's quake but a second pump operated normally as did the reactor, said the utility, the Japan Atomic Power Co. It did not explain why it did not announce the incident until Sunday.

Edano denied there had been a meltdown in the Fukushima Daiichi complex, but other officials said the situation was not so clear.

Hidehiko Nishiyama, a senior official of the Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry, indicated the reactor core in Unit 3 had melted partially, telling a news conference, "I don't think the fuel rods themselves have been spared damage," according to the Kyodo News agency.

A complete meltdown — the melting of the radioactive core — could release uranium and dangerous contaminants into the environment and pose major, widespread health risks.

The steel reactor vessel could melt or break from the heat and pressure. A concrete platform underneath the reactor is supposed to catch the molten metal and nuclear fuel, but the intensely hot material could set off a massive explosion if water has collected on the platform. Radioactive material also could be released into the ground if the platform fails.

The explosion that destroyed the walls and ceiling of Daiichi Unit 1's containment building was much less serious that a meltdown would be — in fact, it was operators' efforts to avoid a meltdown that caused it.

Officials vented steam from the reactor to reduce pressure, and were aware that there was an explosion risk because the steam contained hydrogen, said Shinji Kinjo, spokesman for the government's Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency. The explosion occurred when hydrogen reacted with oxygen outside the reactor.

It is unclear how far the impact of a meltdown might reach. In the United States, local communities plan for evacuation typically within 10 miles of a nuclear plant. However, states must be ready to cope with contamination of food and water as far as 50 miles away. Radioactivity can also be carried to faraway places by the winds, as it was in the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, though it will become increasingly diffuse. Acute radiation deaths would normally be expected only much closer to the plant.

Japanese authorities have classified the event at Daiichi's No. 1 as a level 4 "accident with local consequences" on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES).

The scale is used to consistently communicate the safety significance of events associated with sources of radiation. The scale runs from 0 (deviation — no safety significance) to 7 (major accident).

The 1979 Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania was a level 5 ("accident with wider consequences"). The 1986 Chernobyl disaster was a level 7 ("major accident").

The U.S. is not expected to experience "any harmful levels" of radiation from Japan's stricken reactors, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission said Sunday.

"All the available information indicates weather conditions have taken the small releases from the Fukushima reactors out to sea away from the population," the NRC said in a statement.

"Given the thousands of miles between the two countries, Hawaii, Alaska, the U.S. Territories and the U.S. West Coast are not expected to experience any harmful levels of radioactivity."

The reactor that exploded at Chernobyl, sending a cloud of radiation over much of Europe, was not housed in a sealed container as those atDaiichi are. The Japanese reactors also do not use graphite, which burned for several days at Chernobyl.

Prime Minister Naoto Kan on Sunday sought to allay radiation fears: "Radiation has been released in the air, but there are no reports that a large amount was released," Jiji news agency quoted him as saying. "This is fundamentally different from the Chernobyl accident."

Japan's nuclear crisis was triggered by twin disasters on Friday, when an 8.9-magnitude earthquake, the most powerful in the country's recorded history, was followed by a tsunami that savaged its northeastern coast with breathtaking speed and power.

More than 1,800 people were killed and hundreds more were missing, according to officials, but police in one of the worst-hit areas estimated the toll there alone was more than 10,000.

All of the reactors in the region shut down automatically when the earthquake hit. But with backup power supplies also failing, shutting down the reactors is just the beginning of the problem, scientists said.

"You need to get rid of the heat," said Friedrich Steinhaeusler, a professor of physics and biophysics at Salzburg University and an adviser to the Austrian government on nuclear issues. "You are basically putting the lid down on a pot that is boiling."

"They have a window of opportunity where they can do a lot," he said, such as using sea water as an emergency coolant. But if the heat is not brought down, the cascading problems can eventually be impossible to control. "This isn't something that will happen in a few hours. It's days."

Japan's nuclear safety agency said 1,450 workers were at the Daiichi plant on Sunday, its usual staffing. The workers were in protective gear and were taking shorter turns than usual in units 1 and 3 to limit their exposure, agency spokesman Yoshihiro Sugiyama said.

The emergencies at the nuclear plants have led to an electricity shortage in Japan, where nearly 2 million households were without power Sunday. Starting Monday, power will be rationed with rolling blackouts in several cities, including Tokyo.

Japan has a total of 55 reactors spread across 17 complexes nationwide.