WARREN MICH. – For voters here in this blue-collar suburb of Detroit, presidential elections are always about one thing – jobs.

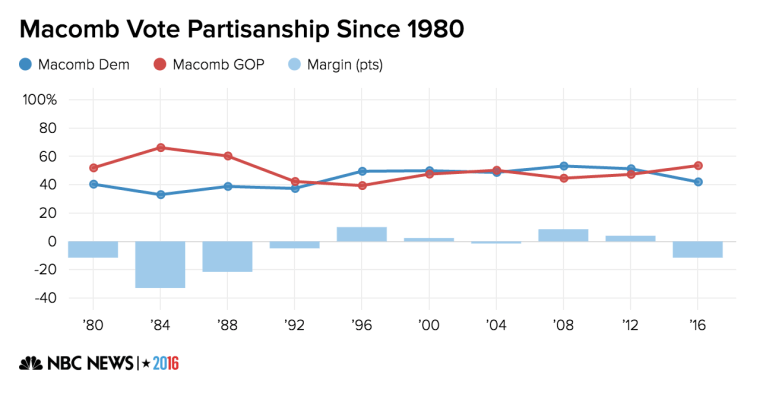

Macomb County, birthplace of the “Reagan Democrats,” voted for Barack Obama for president in both 2008 and 2012. This year, it went big for Donald Trump – 54 percent to 42 percent for Democrat Hillary Clinton.

And it was not alone. Throughout the Industrial Midwest, blue-collar suburban counties “flipped” in 2016. They were crucial to President-elect Trump’s wins in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin.

What they want is clear -- restore the region’s economy.

“I felt that Trump was going to bring the jobs back into the U.S., that was my whole thing. And he was going to try and close the borders so we don’t have so many jobs going out of the country” says Kenneth Lombardo, who is in a job retraining program at Macomb Community College. He’s an Obama-turned-Trump voter.

Michelangelo Ivone also voted for both and sees the issue as “change.” He voted for Obama because he wanted to change the direction of the country in 2008 and he was ready to try another course this year. “Regardless of party,” he says, “who’s going to do right for myself.”

When people here talk about jobs, they mostly mean manufacturing. Those jobs are the economic engine for the area and they declining. In 2000, 26 percent of the jobs in Macomb came from manufacturing. By 2014, that figure was down to 20 percent.

To be clear, things aren’t terrible in Macomb County. The August unemployment rate was 5.9 percent, only a bit higher than the national average of 5.0 percent. And the median household income, $54,000, is slightly above the national median of $53,000.

But things are also not what they used to be either.

In 2000, the median household income in Macomb was $52,000. In today’s dollars, that would be the equivalent of about $71,000. Since the turn of the century, Macomb has gone from being an economic winner to being a true middle-of-the-pack performer.

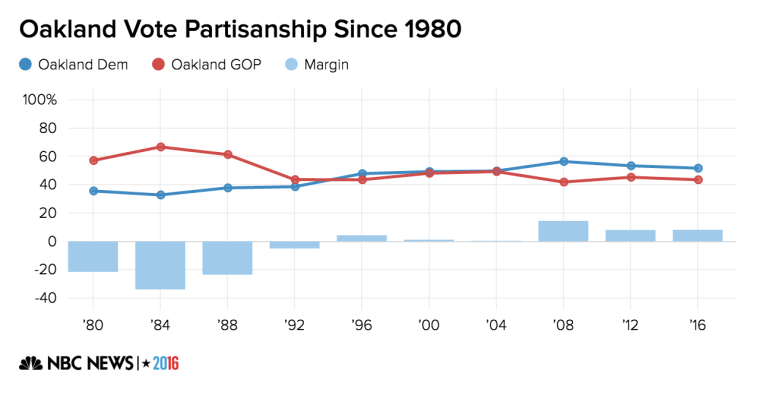

Not helping those income numbers are the county’s education rates. Only 23 percent of the 25-and-over population in Macomb has a bachelor’s degree, that’s compared to 29 percent nationally and 44 percent in neighboring Oakland County.

Polls show that regions with higher education levels went heavily for Clinton, with Trump winning in places with lower levels.

In metro Detroit, Clinton won Oakland County by the exact margin that Barack Obama did in 2012, 8 points, while Macomb flipped in a big way toward Trump.

And voters here have strong feelings – and personal stories – of the negative impact trade agreements such as NAFTA have had on their lives.

“I had a job at General Dynamics and my company lost that contract. It went overseas so that’s how I got laid off,” says Maurice Wiener, another re-trainee. “Bill Clinton signed the free trade act on his way out of office, why would you want Hillary, who’s for the same thing?”

Several of the workers at the re-training center talked of needing to “take a few steps back.” They feel the economic changes that have been remaking the country are leaving them behind and that has stirred resentment.

“There were a lot of people who were sick of what had been promised and not done, not just by one administration or another, but by multiple ones. It just reached a critical mass,” says Steve Truscon, who also voted for Trump. “Most people would agree he is the bull in the China shop. Right now things are so inbred in Washington, we need to get someone in there who will bust things up a little bit.”

At Little Joe’s Coney Island, not far from the Detroit border, owner Nick Fetahu says he sees and hears a lot of the anger. The TV behind the counter is always on sports now because when he tunes into news it starts arguments. Even the news channel he chooses can create hard feelings and customers ask him to change to the channel they feel most connects to their point of view.

“It makes no difference to me. I just want happy customers,” he says. “Whoever is president Hillary or Trump, I have to put on this apron.”

But he says he could tell long before the election that Macomb was going to vote for Trump. Business has been steady he says and has recovered to normal pre-recession levels, but many of his customers are unhappy. “They think he’s going to make a change,” he says.

Brian Hanselman, in a nearby booth, is one of those customers. He says he didn’t even bother voting in 2008 or 2012, but came out to vote for Trump this fall because he might “bring the jobs back.”

Hanselman was a painter before the recession and had a union job that gave him a good wage and health insurance. That all went away when the Detroit area economy cratered. He’s now working contract-painting jobs when he can, he says.

“For years I thought what’s the point in voting. I’ve always said it’s fixed,” he says. “But I voted this time because I had to. I think Trump will stand up to Congress and stand up for the little guy.”

But the recent history makes one thing clear – the voting behavior in places like Macomb is anything but permanent. And Trump’s mission – “bring jobs back” – is not an easy one. Manufacturing has been declining in the United States for decades.

In 1980, nearly 20 million Americans worked in manufacturing, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Today, that number is fewer than 13 million – that decline has happened as U.S. population has grown by about 90 million. Some of that decline is surely about foreign competition. But it’s also about automation and robotics – what many of the job re-trainees in Macomb were learning.

What does that mean for the voting habits here? Michelangelo Ivone has a simple answer. “If Trump doesn’t do what he says, we’ll vote for change again.”