Women in Kentucky are disproportionately affected by the state’s HIV criminalization laws, according to a new report.

Of the 32 arrests for HIV-specific offenses in the state since 2006, all but one were the result of a state law that criminalizes prostitution — including the “procurement” of prostitution — for people living with HIV, the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law found. The remaining arrest was under a Kentucky law that makes it a crime for someone with HIV to donate organs, skin or tissue.

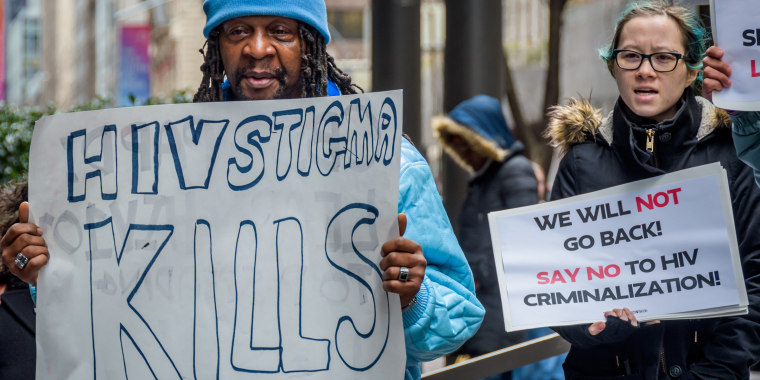

HIV criminalization laws make the virus's transmission — and sometimes perceived exposure to it — a crime. They can also increase penalties for separate crimes based on a person’s HIV status, the institute, which authored the report, said.

Women made up nearly two-thirds, or 62 percent, of individuals who were arrested for HIV-related crimes in Kentucky since 2006, according to data from the Kentucky State Police’s Uniform Crime Reporting section.

In addition to the prostitution and organ donation laws, at least two others can criminalize people living with HIV. Under Kentucky law, it’s a misdemeanor for a person living with HIV to “cause a police officer engaging in their official duties to come into contact with” their bodily fluids. The offense can be upgraded if the person knows that they have a “serious communicable disease” and if medical evidence shows that their contact could cause transmission.

The state has also prosecuted people living with HIV under its wanton endangerment law, which makes it a felony for someone who “under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to the value of human life…wantonly engages in conduct that creates a substantial danger of death or serious injury to another person,” though the Williams Institute left this law out of its analysis. The report found that the state first used the law to prosecute a person living with HIV for not disclosing their status to a sexual partner in 1998.

Of the women who were arrested under Kentucky’s HIV-related laws, the institute found that white women were particularly overrepresented. They made up 59 percent of all HIV-related arrests, though they made up 43 percent of the state’s population in 2019 and only 8 percent of the state’s population of people living with HIV. Researchers said state records did not contain gender identity data, so it’s unclear whether any of these arrests were of transgender women.

Nearly all, or 97 percent, of the arrests were related to sex work. Four of those were charged as procuring prostitution and one was charged as solicitation of prostitution, the report found.

“A person can be arrested for sex work in the state without engaging in actual sex acts,” lead author Nathan Cisneros, HIV criminalization analyst at the Williams Institute, said in a statement. “That means Kentucky law can apply a felony charge — which carries a prison term of up to five years — to people living with HIV without requiring actual transmission or even the possibility of transmission.”

Kentucky is one of 35 states that have laws that criminalize exposing someone to HIV, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J. Maurice McCants-Pearsall, director of HIV and health equity at the Human Rights Campaign, told NBC News earlier this year that the penalties for violating these laws can include prison time: 18 states impose sentences of up to 10 years and 12 states impose sentences of up to 20 years.

Those penalties are “not based off of behavior motivated by intent to harm,” he said. “This is based off of you not disclosing your status or merely the perceived exposure to HIV, and that’s ridiculous, totally ridiculous.”

Proponents of keeping the penalties argue that without them, someone might intentionally transmit HIV without fearing repercussions.

Earlier this year, for example, Virginia reformed a law that makes it a felony to intentionally transmit HIV. Advocates hoped to get the charge for such a crime reduced to a misdemeanor, which didn’t happen, NBC News reported. But the reform legislation that passed does require proof of actual transmission, rather than just exposure. At the time, state Sen. Mark Obenshain, a Republican, told The Washington Post that he found it “stunning that we would want to eliminate the felony for what is potentially fatal, deadly conduct.”

But advocates say there are other laws that make it a crime to intentionally transmit a disease, and that HIV criminalization laws disproportionately affect people of color and transgender women. The CDC describes them as “outdated,” saying that they “do not reflect our current understanding of HIV” after 30 years of research and biomedical advancements to treat the virus and prevent transmission.

“In many cases, this same standard is not applied to other treatable diseases,” according to a CDC website about the laws.

Eleven states also criminalize spitting or biting for people living with HIV, “even though we know the science tells us that it is not possible to transmit HIV through saliva.”

Multiple studies have found that the laws do not deter behavior that would increase the risk of transmitting HIV, and some researchers have argued that they actually hurt public health efforts to prevent and treat HIV.

Nora Darling, policy manager at AIDS United, which works to end the HIV epidemic, said shame and stigma “are among the most persistent challenges we face to end the HIV epidemic in the United States.”

“The stigma associated with HIV is what keeps people from accessing the prevention, treatment and support tools we know can end the HIV epidemic,” Darling, who uses gender-neutral pronouns, said in a statement.

Laws like the ones in Kentucky are rooted in and increase stigma, they said. They added that such laws aren’t equally enforced “and are often used to target already overpoliced communities,” like sex workers, as the Williams Institute report shows, but also communities of color, immigrants, transgender people and people who use drugs.

“It isn’t a coincidence that these are also some of the communities hardest hit by the HIV epidemic,” Darling said. “Public officials should be doing all they can to reduce stigma and the overpolicing of our communities. They have a moral obligation to follow the science and create a legal, social and political climate where people living with and vulnerable to HIV get the care we need.”