With his strapping frame and finely chiseled features, Rock Hudson epitomized masculinity and heterosexuality in the 1950s and ’60s, starring in a slew of romantic dramas and comedies that cemented his status as one of the final leading men of Hollywood’s Golden Age. But after becoming one of the first celebrities to publicly disclose their HIV/AIDS diagnosis, Hudson unwittingly changed how the world responded to the epidemic.

The enduring legacy of Hudson — who died just shy of his 60th birthday in October 1985, less than three months after his publicist publicly confirmed his diagnosis — comes back into focus in “Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed,” which premieres Wednesday on HBO. Using a wealth of archival materials, including personal photographs, home videos and interviews with colleagues, close friends and lovers, the film chronicles the actor’s journey from growing up as Roy Scherer Jr. (and later Roy Fitzgerald) in a small town in Illinois to becoming Hollywood’s Rock Hudson, one of the most venerated movie stars of his generation — all while under the ever-present threat of being publicly outed as gay (though his sexuality was considered an open industry secret).

For documentarian Stephen Kijak, who first encountered Hudson on the silver screen in one of director Douglas Sirk’s melodramatic films of the 1950s, the blurring divide between Hudson’s private life and manufactured public persona, as well as his posthumous impact on the HIV/AIDS crisis, provided fertile ground to reintroduce the actor to new generations of cinephiles.

“Looking back at his body of work, knowing what we now know, is like gazing into a hall of mirrors: Roy Fitzgerald, gay man, performing the role of Rock Hudson, manly movie star, who would eventually take on roles that interrogate and exploit his double life,” Kijak wrote in his director’s statement.

In 2020, Kijak, who had recently directed the four-part HBO Max docuseries “Equal” about the fight for LGBTQ rights, was approached by his producing partners about helming a new Hudson film called “Accidental Activist.” Believing that the descriptor “could be a little misleading” for the scope of their project and wanting to respect the AIDS activists who were “on the front lines, fighting for their lives, from the very beginning,” Kijak said he elected to change the title to “Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed,” after Hudson’s star-making turn opposite Jane Wyman in Sirk’s classic 1955 romance film of that name.

Taking a page from the 1992 film “Rock Hudson’s Home Movies” — a quasi-documentary, or “essay film,” in which director Mark Rappaport playfully mined the queer subtext and double entendres from Hudson’s movies — Kijak said he wanted to look for “deeper, broader connections” in his work, but he wanted these connections “speaking to all aspects of his life, not just his queerness.”

In pursuit of this goal, Kijak would occasionally have Hudson’s films talking to each other in a suggestive way that alluded to his personal life. For instance, “Rod Taylor gets a phone call in ‘A Gathering of Eagles’ from Rock Hudson in ‘Pillow Talk’ and gets asked out on a date,” the director explained.

“I could have done a lot more of it,” Kijak said, “but the idea was to create this sort of fantasy space within film, so that he could be himself in a movie of the ’50s and ’60s and be a gay man in that world.”

But that isn’t to say that Hollywood was completely oblivious to Hudson’s love life. At the behest of his notorious agent, Henry Willson, who was known for grooming his younger male clients to maintain a more macho image, Hudson married Willson’s secretary, Phyllis Gates, in 1955 — a union that lasted only three years — but questions continued to swirl about the actor’s sexuality, according to the film. Given that Hudson was generally well liked and well regarded among his peers, many of his co-stars, including Doris Day and Elizabeth Taylor, as well as the people who had him under contract at Universal Studios, protected his potentially career-ending secret.

Nevertheless, as time went on, there seemed to be a more deliberate creative choice to play into the duality of Hudson’s public and private selves on the big screen, Kijak said. His films with Day — “Pillow Talk” (1959), “Lover Came Back” (1961), “Send Me No Flowers” (1964) — “constantly give him a character that is pretending to be gay or effeminate when, really, he’s this straight, butch guy, but he’s doing that to trick [Day’s character], to maybe get her into bed.”

Hudson’s on-screen work, however, told only one side of his story. Under the guidance of author Mark Griffin, who wrote the most recent biography of the matinée idol, Kijak found it was a lot easier than he had expected to get access to the key players in Hudson’s life, which he considers “an unbelievable gift.”

The producers also made a deal with the actor’s estate, which gave the production team unprecedented access to his personal belongings.

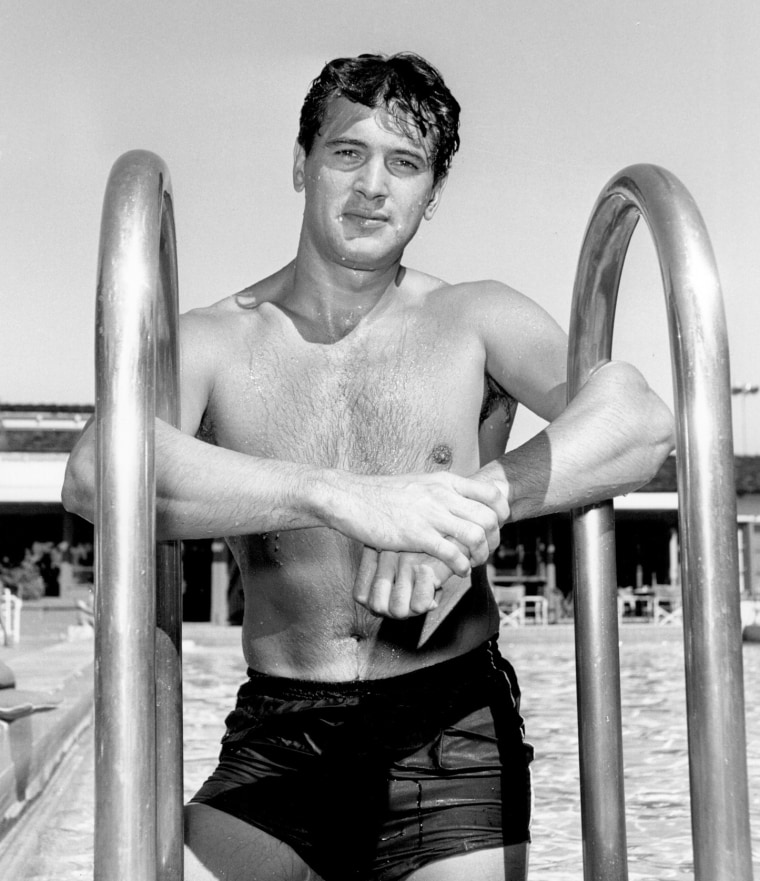

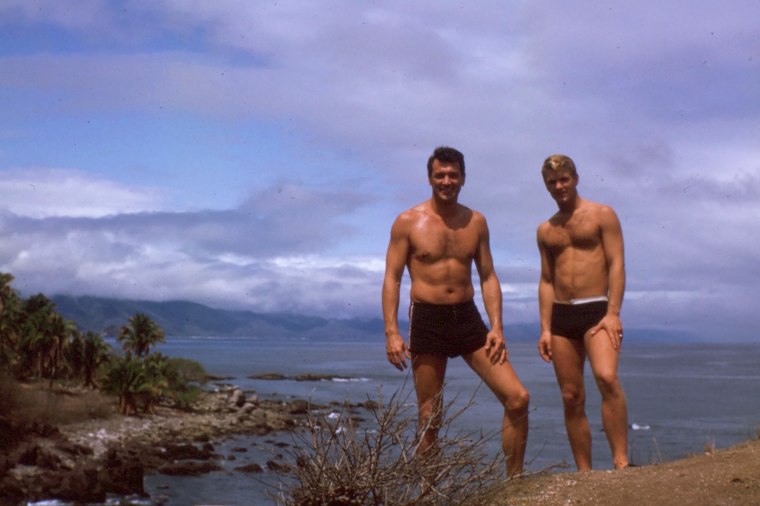

“We unearthed this box of 1963 color slides, and it’s Rock and his boyfriend, Lee Garlington, on a road trip on the beach, in tiny bathing suits, looking really hot,” Kijak recalled with a laugh. “Those were all unpublished. I don’t even think [his estate] knew that they had them, or they had been forgotten.”

The heart of the film, Kijak said, is the collection of interviews with gay men, including Garlington, who were part of Hudson’s inner circle and spent time at his Beverly Hills mansion that they dubbed “the Castle.”

“They form a really neat, compact arc that will bring you from the pre-Stonewall era before gay liberation to the other side of the AIDS crisis,” he said. “It gives you an inside look at his life in a very intimate way through real-life anecdotes, memories and experiences that I don’t think you’d get by just putting famous talking heads in a row.”

Although many of his friends were in long-term partnerships, Hudson was never truly able to commit himself fully to one person, valiantly trying to be, as a Vanity Fair article once put it, “all things to all people.” Hudson’s close friend, George Nader, quit acting in part because he “just wanted to live his life” and “couldn’t deal with the game playing anymore,” Kijack said, “and Rock just could never do that.”

“I think he burned through a lot of relationships because he had to constantly code-switch. He was taking women out in public, but then he’d have a few drinks and show up at someone’s apartment late at night,” Kijack added. ”Everything had to be kept under wraps.”

After pivoting to television and starring in NBC’s “McMillan & Wife” in the ’70s, Hudson’s life collided with the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the ’80s. Despite his declining health, Hudson, who Kijak said “was living in massive denial right up until the end” due to the uncertainty of the virus, landed a recurring role on the ABC prime-time soap opera “Dynasty,” in which he shared a now-infamous, passionless kiss with leading lady Linda Evans. In the documentary, a tearful Evans recognized that, at a time when some feared that kissing could pass on the virus that causes AIDS, Hudson was merely trying to protect her.

A few months before Hudson’s death, his French publicist, Yanou Collart, revealed his diagnosis to the media, setting off a firestorm of AIDS-related panic in Hollywood.

“None of us are 100% sure where his head was at that moment — how aware or how complicit he was in the revelation, or how in control of the narrative he was — but we do know that it had a massive impact on the way people talked about HIV and AIDS,” Kijak said.

He added that he hopes his film reminds audiences, especially younger generations, of the “horrific” early years of the epidemic and the slow response of the Reagan administration until Hudson elevated discussion of the illness to the mainstream.