When it comes to presenting Indians to the world, the nuances of everyday life can often get lost in translation. And when the story is told through the eyes of Dalit women, oppressed by a confluence of factors that many outside South Asia may never understand, achieving that balance is even trickier.

That was something the filmmakers Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh grappled with while making “Writing With Fire,” a critically acclaimed documentary about the first all-female, Dalit-run newspaper in India. Now shortlisted for an Oscar, the movie follows a group of young women working at the newspaper Khabar Lahariya, as they learn to use mobile phones to document their community’s needs and question those in power.

“This is the story of journalists,” Ghosh told NBC Asian America. “In popular culture in India, you don’t see the Dalit community in positions of power, especially women. And I think there is an opportunity where you can reframe that conversation, simply by letting us observe the work.”

The story opens in Uttar Pradesh, an Indian province notorious for crimes against women. Danger is magnified for women who are Dalits, the name for people born into the most oppressed castes in South Asia’s rigid hierarchy.

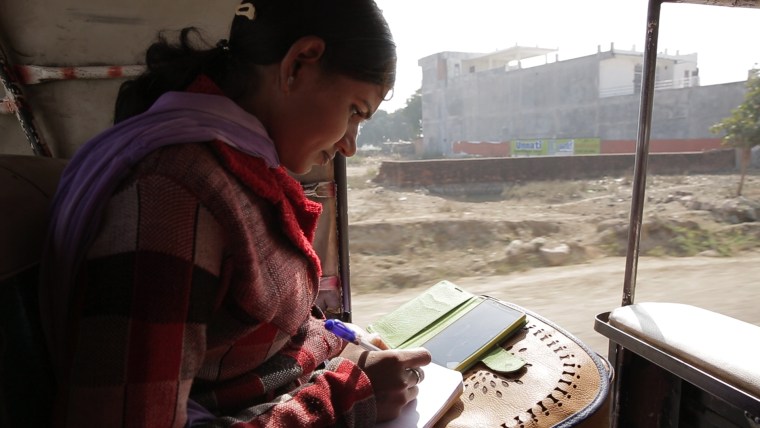

Chief reporter Meera Devi leads a team of journalists, holding up smartphones and recording interviews with people whom the country’s mainstream media might otherwise never capture.

“In our region, a journalist meant you are an upper-caste man,” Devi said in the documentary, recorded in Hindi with English subtitles. “A Dalit woman journalist was unthinkable.”

Thomas and Ghosh’s small camera crew follows the reporters like a shadow as they talk to survivors of violent crimes, families who have lost loved ones to mafia violence, who only trust the women of Khabar Lahariya with their stories. With careful persistence, they take the concerns of their subjects and question officials about why they aren’t doing more.

The women exist in the crosshairs of the very issues they cover. Viewers watch them take buses or rickshaws home to poverty, sexism and family health issues. Devi, a mother who was married at 14, is told by her husband that Khabar Lahariya is destined to fail and that she should stick to her housework. Those assertions are met with Devi's polite but firm, “I disagree.”“The way they carried trauma and turned that into a weapon of purpose on an everyday basis still confounds me,” Thomas said. “When you wake up everyday and a murder or a rape or people not getting access to what is rightfully theirs is coming at you — and you yourself are part of those communities — how do you stay motivated?”

Suneeta Prajapati, Devi's right hand, started working in the mines at the age of 10. Soon after, many residents were forced to leave her village after frequent illegal blasting buried their clothes and food in layers of dust.

But the story isn’t about that. Thomas and Ghosh said they were determined to show the women as they saw themselves — not as victims of their circumstances, but powerful and determined in their resistance. They know the risks that come with their work, and fear being harmed or killed for reporting on corruption, but what’s important to them is that they do it anyway.

“Being a journalist gives me the power to fight for justice,” Prajapati said. “And that’s what I want to be remembered for.”

Devi and Prajapati are often seen standing alone in crowds of men, having back and forths with those telling them to “get out” or to “stay within their limits.”

“Instead of patronizing me, why don’t you give me an interview?” Prajapati asked one man who yelled at her. And one by one, the other men in that crowd volunteered to speak with her.

Raw and tense moments like these were important to show for Thomas and Ghosh, who say that Dalit men living in poverty are also victims of the same patriarchal systems that oppress the women they attack.

“That’s also a conscious choice,” Thomas said. “You don’t have these stereotypical portraits of men. Men as nasty, men as debilitating, but also men as complex being and survivors of patriarchy and casteism themselves and how that complicates relationships for these women.”

From the outset, Thomas and Ghosh aimed to present their work to an international audience. Explaining caste was one of the primary hurdles they encountered.

“I think the fundamental rule that we use in the edit was not to oversimplify for an Indian audience and not to overcomplicate it for an international audience,” Ghosh said.

With a 100 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes, the film has been praised across the board as a journalism story that’s never been told before. Thomas and Ghosh say they embedded themselves with the women, often accompanying them minus the cameras.

“One of the paradigms that we wanted to challenge was extractive storytelling,” Ghosh said. “A lot of times that you’d have filmmakers from the West coming into India, telling us our own stories, in a way that, for lack of better word, will leave you annoyed.”

As a brief written explanation of caste at the beginning of the film fades to black, the filmmakers leave it to the Dalit women themselves to show in their everyday lives how they are contending with and transcending systems meant to hold them down. For Devi, she sees it in being denied housing and her kids being mocked at school. But, as she’s doing with Khabar Lahariya, she encourages her children to challenge and question everything.

“When Dalit women succeed, it redefines what it means to be powerful,” she said.