ATLANTA — Robert Whitley smiled wide as he showed off the mountains of merchandise inside his sprawling warehouse. There were stacks of paper towels that rose to the ceiling. Enough Huggies diapers to supply a day care. And large vats of blue and green laundry detergent of mysterious provenance.

“At the right price, I don’t care what it is, it’s going to sell,” Whitley, a 71-year-old grandfather with a salt-and-pepper mustache, said during a recent tour of his facility.

He may not fit the profile of a crime boss, but federal prosecutors have described Whitley, who goes by Mr. Bob, as the leader of a multimillion dollar shoplifting ring.

From 2011 to 2019, he sold more than $6 million worth of stolen goods — everything from razors to Rogaine to teeth-whitening strips — on Amazon and other online marketplaces, according to court papers. Prosecutors say he paid professional shoplifters to steal specific items from drug stores, supermarkets and big box retailers across Georgia.

The case against Whitley was built not just by federal agents but corporate investigators with CVS, Target and Publix, representing the kind of collaboration that has grown more prevalent amid what industry groups say is a historic spike in organized retail crime.

Whitley was sentenced to nearly six years behind bars last October after pleading guilty to one count of interstate transport of stolen property. He’s expected to report to federal prison in June.

While he acknowledges that he used to buy and sell pilfered goods, Whitley scoffs at the idea that he ever operated what federal prosecutors described as a “well organized criminal network.”

“Where I come from, it’s just trying to make a living,” Whitley said.

Organized theft costs retailers billions of dollars each year, a crimewave that industry groups say was plaguing the country before the Covid-19 pandemic and has only gotten worse.

Videos of “smash-and-grab” store robberies have gone viral in recent months, and rampant thievery has caused stores to shut down. At the same time, police departments have scaled back property crime enforcement due to soaring rates of violent crime and criminal justice reforms that have increased the threshold for charging shoplifters with felonies.

National retailers have filled the void with their own armies of seasoned investigators. They spend months and sometimes years gathering evidence against shoplifting rings and present nearly fully formed criminal cases to law enforcement.

Many of the country’s major retailers — Target, Walgreens, CVS, Walmart, Home Depot, Lowe’s and Publix supermarkets — now employ former police officers and sheriff’s deputies who go to such lengths as secretly tailing people whom they believe are part of a shoplifting enterprise, according to a NBC News review of more than 50 organized retail theft prosecutions over the last 10 years.

“We only follow someone if we think they are part of a ring worth $1 million or more,” said Ben Dugan, who heads CVS’ investigative arm, which started to surveil Whitley four years before his indictment. “We don’t do small cases.”

Since 2020, an increasing number of states have launched organized retail crime task forces that pair corporate investigators with police and prosecutors. State attorneys general have created teams in Florida, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico and Illinois. Plans are in the works in Connecticut and Michigan.

But the rise of retail investigators raises civil liberties and privacy concerns, experts say.

These corporate cops use many of the same tactics as law enforcement officers — they surveil and question suspected shoplifters, run license plate searches, and collect large amounts of personal data. But constitutional restrictions that bind the actions of police and federal agents don’t apply to retail investigators, allowing them to do things like question people without reading them their Miranda rights.

“They can operate without the constraints that limit what police can do,” said Jeffrey Fagan, a Columbia Law School professor and policing expert. “They can pretty much do whatever they want.”

How corporate cops operate

The story of how Whitley landed in the FBI’s crosshairs begins about eight years ago.

Inside several CVS stores in central Georgia, managers noticed something alarming in the company’s inventory database, which tracks products as they move from a warehouse to store shelves and then to checkout counters. The database was set up to flag missing items even if no one at the store were to notice that a thief ran off with them.

While scanning the system in 2014, store managers in Georgia noticed an inexplicably low count of products like razors and allergy medicine on store shelves. The discovery led to the arrest of three professional shoplifters, or boosters, whose thefts resulted in $215,000 in losses for CVS, according to federal court documents.

The boosters told retail investigators that they sold their bounty to a man named Mr. Bob.

Now the corporate investigators had a solid lead. But who was this Mr. Bob, and how big was his operation?

“Is it a guy stealing $100 a day?” said Dugan, who oversaw the probe. “Or is this a real professional shoplifting crew?”

To answer those questions, CVS teamed up with Target, which had also been hit by thieves. In 2016, investigators from both national chains interviewed suspected shoplifters who were behind bars, court records show. The suspects shared Mr. Bob’s description, the cars he would drive, and the location of a supermarket that served as a meet-up spot to trade stolen goods for cash.

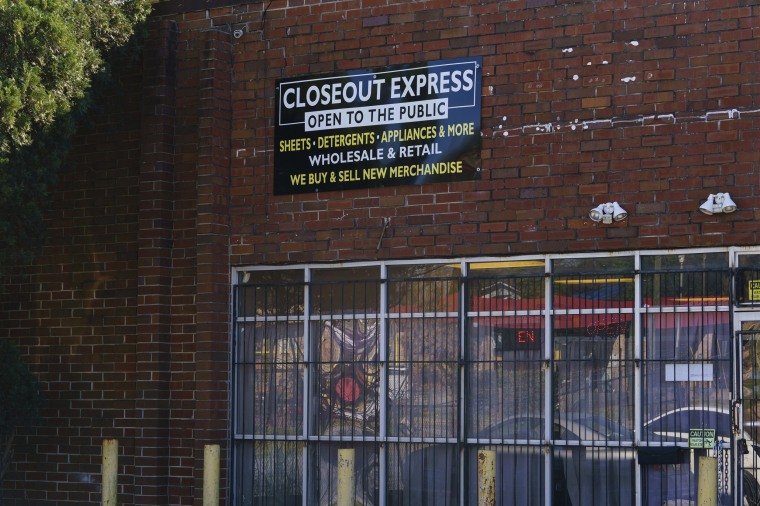

That was enough information for the retail investigators to identify Robert Whitley, the owner of a business called Closeout Express, as Mr. Bob. Over the next three years, investigators from CVS, Target and Publix surveilled Whitley from a distance: They watched as he met people outside his warehouse or at the supermarket. They also followed him to the post office and to his family’s home, court documents show.

Investigators also tailed suspected shoplifters tied to Whitley driving as far as Florida and South Carolina to see what or if they would steal, Dugan said. CVS successfully pitched the case to the FBI, and soon federal agents picked up where the retail investigators had left off. According to court documents, in 2017 they set up a “pole cam” in front of Whitley’s warehouse for an added set of eyes.

The surveillance continued until late 2019. All the while, neither Whitley nor his oldest daughter, Noni, who helps manage the business, had any idea they were being watched.

“I was shocked, just shocked,” Noni said.

Federal agents raided the warehouse and the Whitleys’ homes in November 2019 and seized more than $1 million in stolen goods, prosecutors said. Noni Whitley, who also pleaded guilty, was sentenced to five years in prison.

In interviews with NBC News, the Whitleys admitted to buying stolen products off of boosters, but contend that the value was nowhere near millions of dollars. Noni Whitley said they didn’t have the money to hire their own forensic accountant to dispute the dollar amount, which is tallied by the retailers themselves and used by prosecutors to argue for higher sentences.

‘We are trying to solve this problem’

It’s difficult to quantify the full scope of organized retail theft because the crime can be broken down into multiple classifications and most law enforcement agencies don’t differentiate whether a shoplifter was a lone assailant or part of a larger network.

Moreover, retailers don’t always report shoplifting to the police nowadays. Some national chains say they encourage their workers not to call 911 — to avoid tying up local police — and instead report crimes to in-house investigators.

“We are doing this because we are the victim, and we are trying to solve this problem,” Mike Combs, director of asset protection for Home Depot, said of the role corporate investigators play. “I don’t think there’s enough officers to handle every retailer’s case. You’ve got to help them out.”

Local and federal officials said they happily take any documentation that retailers are willing to share, which often includes in-store security footage, outdoor surveillance images and files gleaned from shoppers’ databases.

“They often give us evidence. They give us leads,” said Kurt R. Erskine, the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Georgia, who oversaw Whitley’s prosecution. “We don’t ever use them as a surrogate for our own investigation. But they can be incredibly valuable partners.”

Registries and databases that track people who make returns without receipts are another deep well for retail investigators. Stores ask shoppers to show proof of identification during such transactions, and court filings show that big box stores keep the information on file.

When police detectives in Ohio found the cellphone number of a man selling stolen tools on Facebook Marketplace in 2019, a detective called Lowe’s. The home repair chain found his phone number in a registry that collects personal information when customers make returns without receipts, said the Perrysburg Township Police Department. That led officers to get a warrant to raid the man’s home, where they found more stolen items.

The man is now serving a five-year sentence in state prison for helping to lead a stolen power tool ring. Lowe’s spokesman Steve Salazar said the chain provides evidence formally requested by law enforcement when the retailer is targeted in a crime. “Lowe’s will continue to prioritize the safety and well-being of our customers and associates,” Salazar said.

The Ohio case troubles Clark Neily, vice president for criminal justice at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think-tank. Neily said there is an absence of court rulings that could provide a check on corporations that freely share customers’ personal information with law enforcement.

“The government’s ability to acquire information about you without a warrant, simply because you have engaged in commerce with a particular company, is much greater than the average person would expect,” Neily said. “The law has not really kept up. There needs to be more in ensuring that companies do not step over the line.”

The lengths retail investigators go in building cases against shoplifting rings — following people across state lines, for instance — also raise questions, policing experts said.

“These retail companies are deputizing themselves as law enforcement and are choosing who to surveil and there’s no oversight at all,” said Ángel Díaz, a lecturer at UCLA Law School who specializes in police surveillance.

Spokespeople for CVS, Target and Home Depot pushed back on the suggestion that their investigators operate without oversight. They noted that judges must sign off on search warrants whenever law enforcement agencies act on evidence provided by retail investigators. The spokespeople also said their investigators undergo extensive training and only surveil people in public places.

“Our investigators operate with specific directives,” said Brian Harper-Tibaldo, a Target spokesman. “Actions such as conducting interrogations, serving warrants or making arrests are managed by law enforcement, not Target investigators.”

But not all retail investigations result in successful prosecutions.

In 2017, Home Depot workers in Florida noticed that thieves were stealing pool pumps and power tools.

Law enforcement documents show that workers didn’t report the thefts to police. Instead, in-house investigators got to work. They ran plate numbers of getaway cars caught on store security cameras, and cross-referenced drivers’ names in databases that identify people who had made returns without receipts. They questioned men caught stealing tools and asked for the names of their accomplices.

Home Depot presented the case to the Volusia County Sheriff’s Office. Detectives checked local pawn shop records to see if any of the boosters had offloaded merchandise. They discovered that at least two were repeat customers of a Richard Hill whose shop was filled with still-in-the-box Home Depot tools, according to the sheriff’s office.

But at the time Hill bought the items, Home Depot had not reported them as stolen to the Volusia County Sheriff’s Office.

Hill told NBC News that he had no way of knowing that he had purchased illicit goods.

“Home Depot hadn’t been telling police that these things were being stolen. They were letting it pile up,” Hill said. The sheriff’s office labeled Hill as the mastermind of a nearly $1 million power tool theft ring.

Months later, the judge dismissed the case after Hill’s attorney argued that there was insufficient evidence showing that his client intentionally bought pilfered products. Despite having his name cleared, Hill said his life is ruined.

“Now here I am — no business, financially hurt, a reputation that’s crushed in the town that I grew up in,” Hill said.

Christina Cornell, a Home Depot spokeswoman, said the retailer had reported the rash of thefts to some law enforcement agencies around central Florida but they didn’t have enough details to list the products’ unique identification numbers in the reports. That means pawn shops would have had no way of knowing they had stolen products in their possession.

“Our teams worked to gather the best information possible, within their limits, to help law enforcement with their investigation,” Cornell said.

A long history

The close working relationship between retailers and the police dates back to the mid-2000s, when Target made its high-tech forensic crime lab available to law enforcement agencies across the country.

Bill Bratton, who was in charge of the Los Angeles Police Department at the time, told NBC News that he used the lab to help reduce the city’s forensic backlog and set in motion a partnership which became a nationwide model. “Police clearly don’t have the resources to do it on our own,” Bratton said. “So that’s why there’s the need for police retail collaboration.”

Bratton and Target went on to spearhead the launch of a private database that allowed police and retailers to input shoplifting incidents, track suspects and the items they were stealing. After he took over the New York Police Department in 2014, Bratton helped to oversee the creation of the Metro Area Organized Retail Crime Alliance, or Metro ORCA, which introduced the Los Angeles model to New York. More than 125 agencies spanning New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania are now using the database.

“It gives law enforcement through the region a chance to search: ‘What does anybody else have out there’?” NYPD Capt. Tarik Sheppard, Metro ORCA’s executive director, said while scrolling through the database. “Everybody’s going to have bits and pieces of the whole pie.”

Dozens of shoplifting databases are now up and running in cities and states from coast to coast, from Florida to Idaho to Oregon.

Leaders of large-scale retail theft rings often recruit people from vulnerable communities — drug addicts, undocumented immigrants, the homeless — to work as shoplifters, according to court documents and law enforcement officials. The ringleaders tend to be adept at using sites like Facebook Marketplace, Ebay and Amazon, to traffic stolen goods, officials said.

CVS’s top investigator said the proliferation of online marketplaces is one of the main reasons organized theft is still so hard to quell.

“It’s just gotten bigger and bigger,” Dugan said.

‘A hell of a business’

Whitley’s business raked in more than $3.5 million in sales through Amazon Marketplace from 2011 to 2018, prosecutors say. But it suffered a major blow when Amazon froze his accounts in 2018, a year before the feds raided his warehouse, Whitley said.

Four years later, his business is still going strong.

On a Tuesday in March, he gave an NBC News reporter a tour of his warehouse filled with name and off-brand paper goods, soap and other products.

“The first rule,” he said at one point, pausing for emphasis. “Price sells.”

Cut off from Amazon, Whitley said he now sells to “street vendors” nationwide. But he’s a bit hazy on the details of where some of his merchandise comes from.

He walked over to a pile of boxes and pulled out a package of Dove body soap.

“I never would have started buying stolen stuff if I had some of this here back in the day,” he said.

He said he pays $33 for a case of 12 bottles of Dove, which he sells for $4 per bottle or $10 for three.

“I buy it from a legitimate business out of New York,” Whitley said. “Big white boy. He sells me a lot of stuff.”

Then he turned to the side and looked out across his warehouse.

“This is a hell of a business, baby,” Whitley said.

(CORRECTION: May 3, 2022, 4:12 p.m.) This article has been updated to clarify comments by Lowe’s spokesman Steve Salazar. He said the chain provides evidence formally requested by law enforcement when the retailer is targeted in a crime — not that it provides customer information without the need for a warrant or a subpoena.