An exhibit documenting violence against and killings of Mexican Americans and Mexicans has won a national grant that will be used to spread knowledge about an overlooked part of American history.

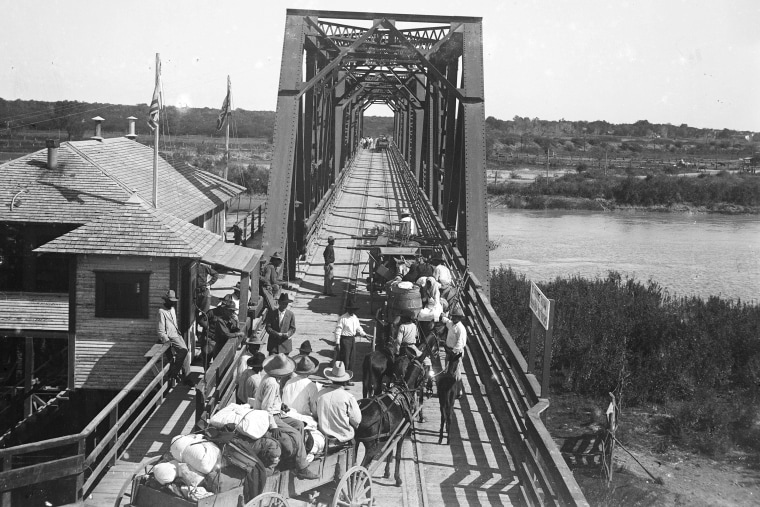

The bilingual exhibit, titled “Life and Death on the Border, 1910-20,” by the Refusing to Forget project, recounts a decade of state-sanctioned racial violence and terrorism that occurred largely on the Texas-Mexico border in the 1900s.

The decade was marked by numerous executions, lynchings and other killings of innocent people. Some people were robbed of their land, and families were driven from their homes. There were deadly raids on communities, as well as illegal detentions.

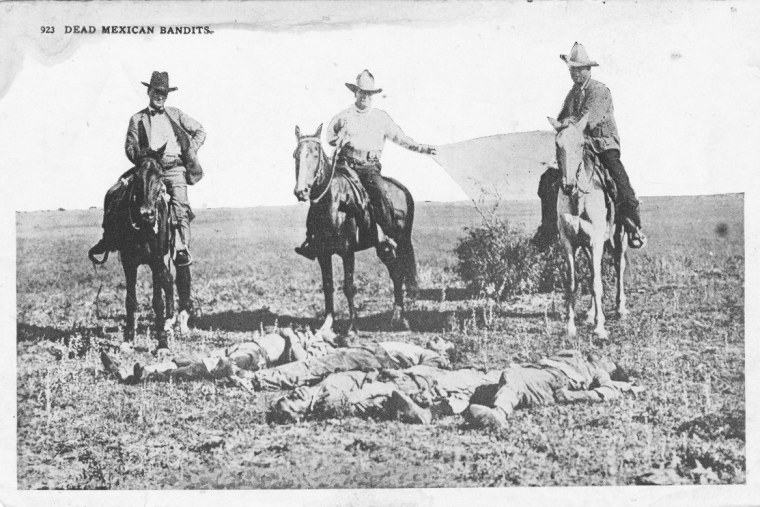

The exhibit relies on state-held documents, photos and even a graphic postcard to tell and support the story of the violence, which was committed largely by the Texas Rangers — a state police force — and local law enforcement.

With the grant of $74,000 from the American History Association, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the organizers hope to take the exhibit to cities across Texas next year, coinciding with the bicentennial of the Texas Rangers.

“This is part of our effort to make accessible a much more accurate history of the Ranger force and its role in inflicting violence in a population that was often labeled as potential revolutionary bandits, because this coincides with the Mexican Revolution,” said a co-founder of the project, Sonia Hernández, an associate professor of history at Texas A&M University.

The exhibit was originally displayed from January to April 2016 at the Bullock Texas History Museum in Austin.

Its showing eight years ago marked the first acknowledgment of the violence by a state institution, said Monica Muñoz Martinez, a project co-founder and the author of “The Injustice Never Leaves You,” which delves into the racial violence.

More than 40,000 people from Texas and across the country traveled to the museum to see the exhibit.

Public history 'so vital for sharing the past'

The area of history is one that many people, even college students, don’t often have access to, Martinez said. During the pandemic, project organizers shifted to distributing the history digitally, but the project has kept getting requests for the exhibit to travel, she said.

“Public history is so vital for sharing the past,” Martinez said.

The traveling exhibit will partner locally with host libraries or museums. The hope is that hosts will be able to add local related artifacts from people in the community and stage events that include local people with ties to the history as experts, said John Morán González, a project co-founder and professor of American English and literature at the University of Texas at Austin.

“It’s about, for one, let’s spread the knowledge about these events to a wider public,” Morán said. “But also that this is really already knowledge that’s embedded in the community, that people have connections to it, and to highlight those connections.”

The exhibit attempts to depict the resilience of communities subjected to the violence and how they tried to fight back.

That included investigative hearings held by the only Mexican American legislator at the time, José Tomás Canales.

“We don’t want to present a history of victimization,” Hernandez said.

“This was what could very well be called an example of an early civil rights movement on behalf of the Mexican American community,” she said.

The $74,000 grant was part of $2.5 million in grants that went to 50 small history-related organizations whose work was interrupted or affected by the pandemic.

Hernandez said that while the exhibit is certain to interest many Mexican Americans and other Latinos, the hope is that it will pique the interest of people of other backgrounds and cultures, particularly as the country struggles with police violence and reform.

“If we want to use history to learn from our past mistakes and make connections to how we really need to engage in a robust discussion about the abuse of power on the part of law enforcement … that involves everyone,” Hernandez said. “That is not a Mexican American issue. That is a ‘we’ issue. That is an American issue.”

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.