HOPLAND, Calif. — On a hillside high above vineyards, olive groves and the meandering Russian River, John Schaeffer has built a low-carbon paradise.

The ranch home he calls SunHawk brims with so much recycled lumber, hardly a tree had to be sacrificed in its construction. Recycled styrofoam walls backed by foot-thick insulation hold in the heat and cold. Even on 100-degree days, the air conditioning is natural — provided by a novel system that pulls air through underground tunnels and over a 10-foot-deep core of cooling stones.

Schaeffer, a solar energy pioneer, powers his home with two banks of solar panels bigger than school buses, supplemented in winter by turbines that spin under the force of a seasonal creek. Together, Schaeffer has calculated, the sun and water power replace dirty grid power that would pump about 83 tons of carbon dioxide a year into the atmosphere.

Until someone has lived off the grid, Schaeffer opines, “They can’t entirely understand where their power comes from or, really, where their life comes from.”

Living lightly on the land has been a calling for Schaeffer since he graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1971, and a business for nearly as long. His Real Goods store in Mendocino County sold one of the first solar panels at retail anywhere in the U.S. More than two decades ago, he augmented the store with the Solar Living Center, a 12-acre campus that promotes sustainable living and farming practices.

Through this commercial and nonprofit enterprise, Schaeffer has shipped more than 7 million catalogs worldwide, educated hundreds of interns and “solarized” 60,000 homes, according to the U.S. Department of Energy, which dubbed the self-described former hippie radical “a green power pioneer.”

Schaeffer, 68, exemplifies a small but determined group of Americans who are not waiting for the government to act, believing their personal actions can help clean the skies, slow spiraling greenhouse gas emissions and begin to chip away at the scourge of man-made climate change. That means not only turning to solar and wind power, but buying electric and hybrid vehicles, putting on a sweater instead of dialing up the thermostat and cutting other carbon-dioxide extravagances like air travel.

A committed liberal who is bridling under the presidency of Donald Trump and the unwinding of environmental regulations by the Environmental Protection Agency and Interior Department, Schaeffer says the growing menace of climate change proves that “the hippies were right.” With Washington standing still or reversing controls on greenhouse gases, he says, individual citizens have even more motivation to take action.

“It accentuates the idea of ‘think globally and act locally,’” said Schaeffer, the father of two daughters and grandfather of four. “People think that the only way to make any real change is to do it themselves. That means lowering their carbon footprint and going off the grid.”

THE EARLY DAYS OF SOLAR

Mendocino County, a two-hour drive north of San Francisco, is a verdant expanse of redwood forests and small towns, sprinkled with old lumber mills and luxe new wineries, many advertising their organic farming practices. A lot of the 87,000 people spread over 3,500 square miles here pride themselves on having an iconoclastic streak. In 2000, Mendocino gave a higher percentage of its votes to Ralph Nader than all but three other counties in America.

The solar-power movement found an early foothold here, too, in large measure because of marijuana growers. Too remote (and illegal) to even think about tying in to the Pacific Gas & Electric grid, the farmers could get by on kerosene and propane for many things, but not to power their radios and eight-track tape players. Many of the farmers who moved to the backwoods in the 1970s would live without a hot shower, but not without the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane.

“That’s why the cannabis industry played a monstrous role in the early development of photovoltaics,” said Jeff Spies, a solar salesman and executive, who helped make the documentary “Solar Roots: The Pioneers of PV.” “A lot of it was the music.”

The cannabis growers had to hide their crops and constantly duck police helicopters searching for illicit farms. But the farmers could visit Schaeffer’s Real Goods store and talk openly about their need for drip irrigation and predator-repelling chicken wire. The same year Real Goods opened, 1978, the store also came up with a new product.

It was provided by an unexpected visitor, who arrived one day in a silver Porsche, representing an upstart North Hollywood enterprise called the William Lamb Co. He left behind three ungainly boxes — roughly a foot wide, two and a half feet long and three inches thick — holding something he called photovoltaics.

“A friend hooked one of them up to a battery and ‘voila!’ there was a charge,” Schaeffer recalled recently of his first real exposure to harnessing the power of the sun. “We'd heard about these things from the space program, but no one had ever seen one. … It was this massive Eureka moment for all of us.”

The seekers and free-range thinkers who frequented the store, in Willits, California, quickly snapped up the three sample panels. Then the 10 Schaeffer bought after that. And the 100 he bought after that. And the 1,000 after that. The entree made the young entrepreneur one of the first people in America to sell solar technology to the public, said Spies, the solar historian.

“What John was doing back in the 1970s and 1980s was really monumental for people living off the grid out here,” said Chiah Rodriques, a second-generation marijuana farmer on the Greenfield Ranch commune west of Ukiah. “It sparked a lot of conversation, a lot of ideas, and really changed people’s lives.”

Rodriques is now farming cannabis legally with her husband, Jamie, and continuing to live off the grid on Greenfield Ranch, a complex of homes and hand-built retreats strung together along dirt roads with names like Radical Ridge. Her family lives with a solar array that Schaeffer initially supplied. In the early days, power remained so low that running something like a blender would dim the lights. But Rodriques’ 4,500-watt system now provides enough juice for a dishwasher, her kids’ video games, a television and more. (Today’s solar panels produce at least twice the wattage per square foot as their 1970s forerunners.)

“I'm proud of our lifestyle,” said Rodriques, 38, the mother of a 17- and a 10-year-old. “And I think it's great that people are coming to understand it's the way to be.”

Rodriques said motivations for going solar have come full cycle — from the idealism of the Back to the Land movement in the ’70s, to the pragmatism of the early pot growers, to a new generation that again emphasizes the environmental benefits of going green. If the children of cannabis grew up with one ethic, it’s that life’s highest purpose is not kowtowing to Washington, or any other central authority.

“The question is, ‘How do we live more sustainably within this model?’” she said. “It’s just good karma.”

‘EVERYONE CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE’

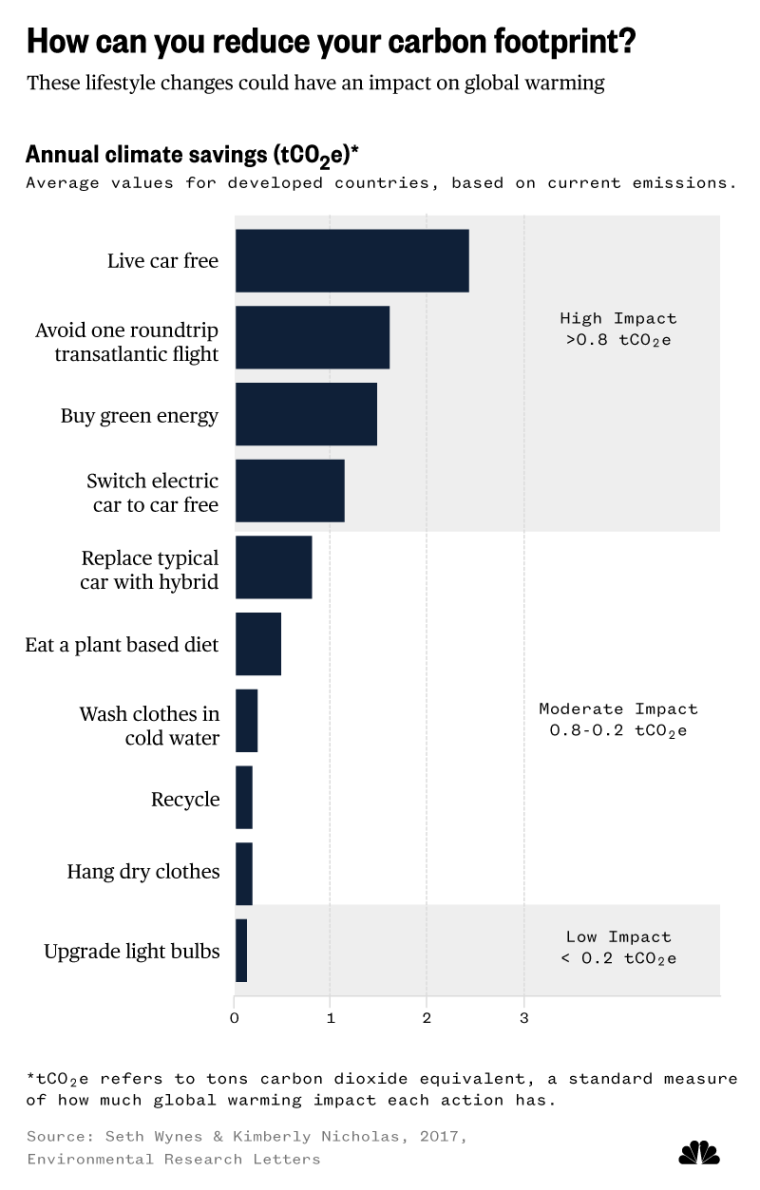

A study a year ago by Sweden’s Lund University assessed a range of ways people can change their behavior to lower their carbon footprint, since excess carbon dioxide emissions produce a warmer atmosphere, which, in turn, lays the groundwork for more floods and droughts and a cascading set of other challenges. The most effective changes — having fewer children or cutting back on air travel — require sacrifices some might consider too great.

But in California, which leads the nation by getting more than 15 percent of its power from the sun, low-carbon acolytes have found measures big and small that can make a difference: washing clothes in cold water and air-drying them; driving hybrid or electric vehicles, or using public transportation or a bicycle; reducing the use of lumber to preserve oxygen-producing forests; and installing wind and solar power systems.

“Everyone can make a difference. The question is, do they really want to,” said Mathis Wackernagel, chief executive of the Global Footprint Network, an international nonprofit that works with people and governments to understand their impact on the Earth’s natural resources.

Wildlife biologist Quinton Martins erected 3.8 kilowatts of solar panels at his home near Santa Rosa — equipment he bought from Real Goods. “It makes no sense to be going backwards and relying on nonrenewable resources which are known to have significant ecological impacts,” Martins said. “Producing our own electricity at home and being totally off the grid feels good. For one, we don’t feel guilty about leaving a light on, or running our appliances.”

Others, like Brenda De Ramus, are starting smaller. A hospital human resources manager, she stopped at the Solar Living Center on her way from her home in Sausalito to a weekend cottage at the north end of the state. She walked out, on a recent Friday afternoon, with a solar-powered pump for a garden fountain.

De Ramus, 55, says she intends to venture further into the self-sustaining lifestyle. “The population is growing, growing, growing, and our resources aren’t keeping up,” De Ramus said. “We have got to understand how our Earth works and how our natural resources work. … So I am excited any time there are ideas put out there about alternative ways of doing things.”

Ricki Lou, a musician from Alameda in the Bay Area, came to the center looking for a solar panel for her car, to provide power on her frequent camping trips. And she brought a friend, who was inquiring about a Solar Living Center internship, which includes lessons on wheat grass cultivation and composting.

Lou, sporting a cowboy hat and patchwork gypsy dress, vowed to be back. “There is just so much knowledge here,” she said.

This may not quite be the “revolution” that Schaeffer hoped for in 1971 when he left Berkeley and visited the Rainbow commune, near the Mendocino County town of Philo. He intended to stay a weekend and instead lasted for six years, believing the world might evolve into a place that disdained pesticides, rejected all forms of discrimination and promoted social justice “everywhere.”

Now, the green power trailblazer sees the revolution as more of a painstaking evolution. Still, he’s determined to expand his mission. In the coming weeks, he plans to rename his solar center “Ecotopia.” Along with the rebranding — the center is a familiar stopping point in the town of Hopland (pop. 807) on U.S. Highway 101 — will come expanded programs and special events. The founder hopes the makeover will double the number of visitors to the center, from an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 a year.

In Schaeffer’s dream, people will flock to Ecotopia, named for a 1970s cult novel about an ecologically balanced paradise on Earth, to take courses in aquaculture (gardens floating atop fish-fertilized pools of water), learn to build structures of rice-straw bales and rammed earth, convert shipping containers into solar-powered micro-homes, and, of course, install their own solar- and wind-power generators.

Schaeffer’s determination to spread the low-carbon gospel is not purely political or metaphysical. Like any retailer, he can’t escape the realities of the marketplace. That means fierce competition from Amazon and big box outlets that are selling goods that once seemed like his speciality, alone.

The resulting plan by Schaeffer and his wife, Nantzy, is for Ecotopia to become even more of a center for education, events and “experiences,” such as weddings and conferences. Schaeffer knows he must expand beyond “the bubble” of green true believers.

There may be more customers in all that, he hopes, and maybe something more. The theme of the new center will be “Step Off the Grid,” which Schaeffer wants to be taken broadly.

“Get out of your head. Think out of the box. Get off the established norms you’ve had your whole life,” he said. “Learn how to grow your own, be your own, talk your own, make your own. ...We want to become a center for that.”

CORRECTION (June 2, 2018, 2:05 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misidentified a structure shown at the Solar Living Center in a caption. The building pictured is a geodesic dome, not a quonset hut.