Anti-Japanese hatred appears to be on the rise in China as the neighbors look to mark a half-century since the normalization of diplomatic ties between Beijing and Tokyo later this month.

The public mood in China has turned against even small signs of Japanese culture in the country in recent weeks, from a woman wearing a kimono to conventions for fans of anime.

Anti-Japanese sentiment runs deep in China, where an intensifying nationalism has also emerged as Beijing clashes with the Western alliance of which Japan is a member. Many resent the refusal of Japan’s government to apologize for war crimes during the Sino-Japanese wars, and its leaders’ repeated visits to shrines commemorating Japanese war criminals.

Even some self-professed fans of Japanese culture, known in China as “ACG,” an acronym for “anime, comic and games,” are sympathetic to the recent surge of resentment.

“Although personally, my own benefit as an ACG fan has been harmed, I still think some of the arguments make sense,” Xinyu Liu, a 23-year-old graduate student in Chengdu, told NBC News, referring to the recent backlash that led to the cancellation of scores of Japanese cultural events across China.

“In the context where Japan has not yet apologized for its war of aggression against China ... this kind of anti-Japanese sentiment that suddenly intensifies every few years is bound to exist for a long time,” he added.

‘You are Chinese’

The most recent flashpoint was a viral video circulating on social media earlier this month that showed a young woman being harassed for wearing a kimono in an area of the city of Suzhou that hosts a number of Japanese restaurants and stores.

In footage uploaded onto China’s internet, a young woman was accosted by an unidentified man who claimed to be a police officer.

“You are Chinese,” a man in a blue shirt yells at the woman wearing a white kimono with pink cherry blossoms, saying he would not be speaking to her in this way if she were wearing Chinese traditional clothing.

He then appears to detain her on charges of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” — a blanket charge commonly used in China to arrest dissidents and journalists.

A hashtag on the subject was seen a total of 150 million times on China’s microblogging website Weibo.

NBC News has reached out to local authorities but received no response, and has been unable to independently verify details of the incident.

It came at a sensitive time, shortly before the Aug. 15 anniversary of Japan’s announced surrender at the end of World War II. While some online commenters expressed support for the woman and accused the man of overreacting, the incident also led to torrents of renewed anti-Japanese rhetoric online, the latest sign of an intensifying nationalism in a country that is increasingly sensitive to narratives that counter Beijing’s.

“Wearing kimonos should not be banned in our society ... but when someone wants to wear a kimono, I would advise them to be aware of their surroundings to avoid upsetting those around them,” Hu Xijin, a nationalist public commentator and former editor of state-backed tabloid The Global Times, wrote on Weibo earlier this month.

Nationalistic hatred also flared up last month after the discovery of the worship of Japanese war criminals at a Chinese temple in Nanjing, a city central to Chinese animosity toward Japan.

A viral social media post showing memorial tablets bearing the names of former Japanese officials at a Buddhist temple sparked national outcry and an investigation that resulted in the arrest of a woman, according to the Nanjing Municipal Party Committee.

The Nanjing massacre, which occurred from December 1937 to January 1938, saw six weeks of systematic mass murder and rape of the city’s residents by Imperial Japanese troops.

The recent incident “has seriously impacted the bottom line of society’s morals and seriously hurt the feelings of the nation, it is shocking and outrageous,” the party committee said in a statement last month.

The ensuing outrage turned against Japanese cultural events including summer festivals and anime conventions across the nation. Traditional Japanese summer festivals, known as matsuris, have been held across China for years.

Although China and Japan — the world’s second- and third-largest economies — are important trade partners, Chinese companies are also distancing themselves from any perceived ties with Japan after public pressure. Chinese lifestyle retailer Miniso, which sells Japanese-inspired products, apologized on Aug. 18 for advertising itself as a “Japanese-designer brand” and vowed to “de-Japanify” the company by March 2023.

Public opinion in Japan is also hostile toward China — a joint survey conducted last year by organizations in the two countries found that more than 90 percent of respondents in Japan had a negative impression of China, compared with about two-thirds of respondents in China who viewed Japan negatively.

But unlike previous waves of anti-Japanese sentiment in China, which were often stoked by state propaganda, this one appears to be more organic, experts said.

“We shouldn’t deny a degree of agency to Chinese people. … Not every case of anti-Japanese sentiment in China should be immediately connected to propaganda campaigns,” said Aurelio Insisa, an adjunct assistant professor in the history department at the University of Hong Kong.

“These are just the result of the increasing relevance of nationalism in Chinese society,” he added.

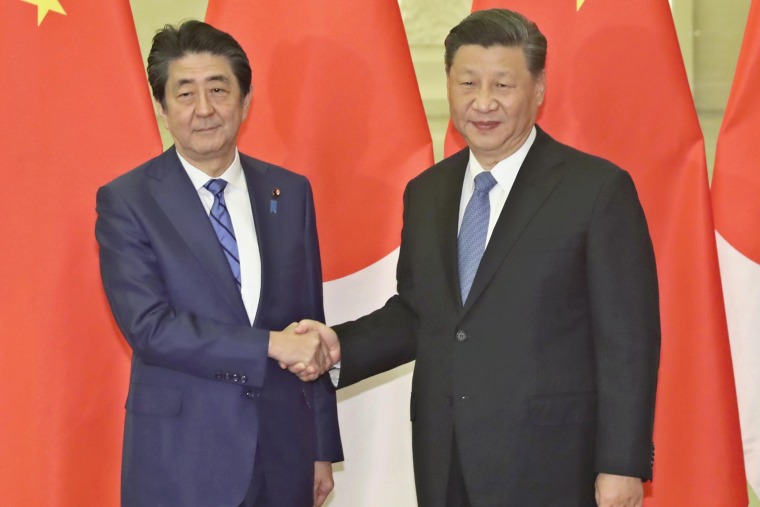

The assassination of Japanese political giant Shinzo Abe in July unleashed a flurry of celebratory comments online in China, with many referencing war crimes committed during the Nanjing massacre as reasons to celebrate Abe’s death.

Insisa noted that China’s tolerance of this anti-Japanese sentiment on its heavily censored internet allows Beijing to signal its current attitude toward Tokyo to the public.

The renewed resentment toward Japan comes ahead of the 50th anniversary in late September of the re-establishment of diplomatic ties between Beijing and Tokyo, and as regional tensions rise in the wake of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, which triggered unprecedented Chinese military drills and deepened Chinese suspicion that Tokyo is working with Washington to use the Taiwan issue to contain China.

Beijing also criticized Japanese Cabinet ministers who recently marked the anniversary of the end of World War II by visiting a Tokyo shrine that memorializes Japanese war criminals.

“The negative move of Japanese political leaders on the issue,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin said at a regular news briefing, “once again shows the Japanese side’s erroneous attitude toward historical issues.”

NBC News has reached out to China’s Foreign Ministry for further comment.

“What we see is that there is a staying power to the kind of anti-Japanese sentiment that has remained after all these years,” Insisa said. “So the point here is that the Chinese state in a specific moment of crisis may tap into this nationalism and Chinese nationalism is impossible to separate from the complicated relation with Japan.”