HONG KONG — Fifteen nasal swabs down, one to go.

As the coronavirus pandemic enters its third year, traveling to Hong Kong is more complicated than ever, if you can get here at all.

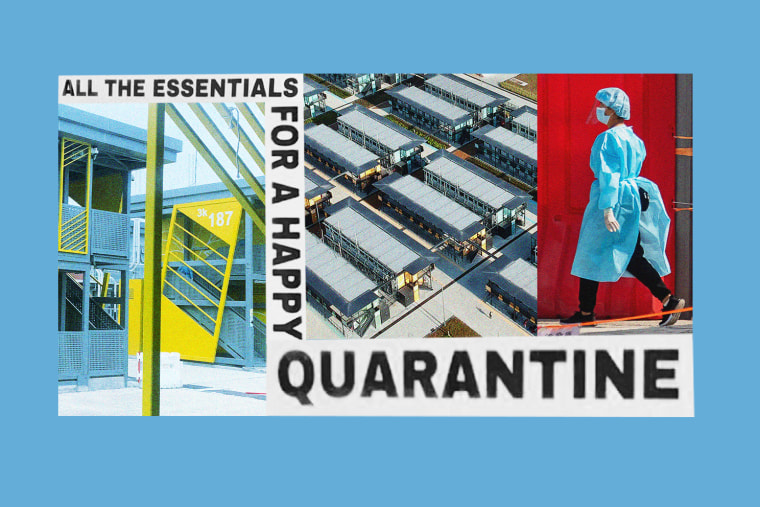

With some of the strictest quarantine requirements in the world, the Chinese territory has become an international outlier as countries struggle to craft a return to some sort of normality. Almost all international arrivals are required to self-isolate in a hotel room for 21 days and submit to a slew of PCR tests to make sure they didn’t bring the virus with them.

For residents like me traveling from the United States, United Kingdom or 13 other countries, the emergence of the omicron variant has brought an additional requirement: The first four nights must be spent at a bare-bones government camp in rooms about the size of parking spaces.

Not long after I returned to Hong Kong in late December, entry was prohibited entirely for anyone with recent travel history in eight countries, including the U.S. and the U.K., greatly adding to the number of Hong Kong residents already stranded overseas as more flights are canceled or banned for carrying too many Covid cases.

As the U.S. and many other countries relax pandemic restrictions despite record case numbers, the situation could not be more different in Hong Kong, which has almost no cases but is tightening its rules by the day.

The global business hub has largely succeeded in its goal of shutting out the virus, but at an increasingly heavy cost — and now it is contending with its own outbreak of the highly transmissible omicron variant, in what may be the biggest challenge yet to its “zero-Covid” strategy.

Fighting off omicron

The zero-Covid approach has its advantages. Until the recent omicron outbreak, Hong Kong had gone months without a single local case, enabling its 7.4 million people to go about their daily lives without fear of infection. The city’s Covid policies have kept overall cases (about 13,000) and deaths (213) to a minimum, avoiding the mass casualties and overwhelmed hospitals that have brought such grief and despair in the U.S. and elsewhere.

But the border closures, quarantine rules and flight bans have also caused a different kind of heartache: babies still strangers to their grandparents overseas, last goodbyes and funerals missed, and families kept apart for years on end. And now the relatively normal daily life gained through those sacrifices has been disrupted by the government’s furious efforts to stave off omicron.

The omicron outbreak, which began in late December, has grown to include scores of cases in what officials are calling a “fifth wave.” Police have arrested two former flight attendants for Cathay Pacific, Hong Kong’s flagship carrier, who are accused of starting the outbreak by violating quarantine rules.

In addition to suspending in-person schooling, the government has closed bars, gyms, movie theaters and beauty salons and banned dine-in service after 6 p.m., drawing an outcry from businesses. This week, officials also ordered that 2,000 hamsters and other small animals be culled after the discovery of virus cases tied to a pet shop.

Hong Kong’s zero-Covid strategy is in line with mainland China, where 20 million people in three cities are on lockdown in an effort to stamp out omicron cases ahead of the Winter Olympics in Beijing next month. The outbreak in Hong Kong is expected to further delay plans to reopen its mainland border.

But it also presents a real risk to Hong Kong, which has just reached a 70 percent full vaccination rate. Unlike in many other places, Hong Kong’s oldest residents are among the least vaccinated: Less than 20 percent of those 80 and older have received two doses, compared with 85 percent among Americans 75 and older. Facing little risk of infection in a zero-Covid environment, many Hong Kong seniors didn’t feel compelled to get inoculated; fear of side effects has also played a role.

Vaccination rates are rising, however, after the government — its hand forced by omicron — announced that at least one dose would be required for entry to restaurants and other venues starting next month.

“I think omicron’s very much a blessing in disguise,” said Dr. Ivan Hung, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Hong Kong and a government adviser.

If Hong Kong can get its vaccination rate up to 90 percent or higher, he said, “then we will be in a far better position to open up to the rest of the world, and of course to mainland China as well.”

In the meantime, thousands of close contacts of local cases have been ordered to quarantine since the omicron outbreak. Among them are senior officials and lawmakers who attended a birthday party later found to have at least one infected guest, an embarrassment for Chief Executive Carrie Lam when her government was advising the public to avoid large gatherings.

The quarantine experience

Compared with Hong Kong, I found the U.S. approach to the pandemic alarmingly relaxed. Arriving at immigration in Los Angeles, no one asked to see my Covid test result. Mask-wearing — still required everywhere in Hong Kong except when exercising outdoors — is inconsistent and often done grudgingly.

As the time came to leave, and omicron sent U.S. case numbers soaring, I felt a rising anxiety, not just about the virus itself, but what catching it would mean for my return to Hong Kong.

The quarantine process begins at Hong Kong International Airport, which was once one of the world’s busiest but these days is a ghost town. There were only about 60 people on my flight from Los Angeles on Cathay Pacific, whose passenger traffic is down 99 percent from pre-pandemic levels.

Once off the plane, passengers follow a prescribed path through the airport, with staff members pointing the way to get tested for the virus and receive written quarantine orders. Signs provide updated numbers of the people convicted of violating those orders and the jail time and fines they received.

We waited for our test results at an unused gate, where each passenger was assigned a small table and chair arranged in long rows and facing one direction like we were taking an exam. The freezing terminal was quiet except for the occasional shrieks of small children whose parents were in for a rough few weeks.

A positive result means an automatic hospital stay that can last weeks regardless of symptoms.

So if it’s negative, going to your quarantine hotel — or in my case, the government camp — can feel like a relief.

It’s a short ride to the government camp, Penny’s Bay, which is near the airport and next to Hong Kong Disneyland. In recent days, the quarantine facility has been overwhelmed with close contacts of local cases, leading Lam to apologize after some of those quarantined there complained about noise, undelivered meals and delayed releases.

When I was there, it was quieter, and the food — catered by Cathay Pacific — arrived as scheduled. The staff who came to test me through the window every morning were kind and gentle with the swabs. And unlike the quarantine hotels, the government camp is free.

But staring out the window at Penny’s Bay as staff members dart past, it’s hard not to feel like a zoo animal, pacing anxiously while waiting for the next meal. It may not be the worst experience in the world, but it’s not normal, either.

After the first few days at Penny’s Bay, the hotel is a welcome upgrade (and the transfer is an exciting opportunity to be outside). But it doesn’t change the fact that you’re stuck in that room, at a cost of thousands of dollars. Work helps pass the time for those of us able to work remotely. Food and other deliveries continue to be left outside the door.

Once I checked in, the only people I saw were the ones in full protective gear who showed up to test me daily until Day 7, then every other day after that. With the pre-departure test, a double test on Day 19 and a final one after quarantine ends for good measure, that’s a total of 16 nasal swabs in under a month for those of us coming from the “highest risk” countries.

The cost of zero-Covid

Hong Kong’s quarantine system has kept thousands of virus cases from reaching the community. But with travel opening up in much of the world, businesses say the restrictions are eroding the city’s status as an international financial center. According to results of a member survey released this week by the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong, more than half of respondents said they were more likely to move away because of the pandemic restrictions.

The science of the 21-day quarantine has also been questioned, with critics pointing out that the incubation period for the virus is generally considered to be no more than 14 days. Keeping people in quarantine for longer than that, they say, puts them at risk of being infected by other guests at poorly ventilated hotels.

But beyond that, it’s just difficult mentally.

“I think two weeks is more than enough,” said Alyssa Liang, a children’s book author who is on her second three-week hotel quarantine. The third week is “way past your maximum.”

Liang, who has also served two shorter quarantines in Hong Kong and mainland China, vows that this will be her last one. She and her husband are putting their home up for rent before they go to Canada for the summer. If the quarantine rules are still in place after that, she said, “we just decided not to come back.”

Some people say they enjoy quarantine as an escape from their usual responsibilities, but many others report struggling with claustrophobia, anxiety and panic attacks, said Paul Yip, a professor at the University of Hong Kong and the director of its Center for Suicide Research and Prevention.

“The mental health aspect has been very much neglected,” Yip, co-author of a quarantine wellness guide, said. “When you put someone into quarantine, they are the ones that contribute to slowing down the spread of the epidemic in the city and they should be supported as well.”

This week, the government said free “emotional support hotlines” had been set up for those in quarantine at Penny’s Bay.

Yip said that even colleagues in the mental health field have found quarantine difficult, and that the policy had deterred him from leaving Hong Kong during the pandemic.

“Who wants to be quarantined, for goodness’ sake?” he said.

Experts are divided on how much longer Hong Kong will stay walled off from the world. In the meantime, I’m back in the outside world after weeks of confinement — I just hope the local outbreak doesn’t land me right back at Penny’s Bay.