Transcript

Article II: Inside Impeachment

The Chief Justice Shall Preside

Archival Recording: What feedback have you gotten from your colleagues on not sending the articles yet?

Nancy Pelosi: Absolutely total cooperation. It cracks me up to see on TV, "Oh, pressure builds, the pressure that." (LAUGH) You don’t have a story.

Steve Kornacki: From NBC News, this is Article II: Inside Impeachment. I'm Steve Kornacki. Today is Friday, January 10th, and here's what's happening.

Archival Recording: Are you satisfied, Madame Speaker, that there'll be a fair trial in the Senate?

Pelosi: No. (LAUGHTER)

Kornacki: House Speaker Nancy Pelosi says she doesn't think the impeachment trial in the Senate will be fair. But even so, Pelosi told her Democratic colleagues today that she is preparing to hold a vote to send the articles over to the Senate next week.

Archival Recording: Madame Speaker, whenever you do send the articles, will you send both articles to the Senate?

Pelosi: I will send what was voted by the House, yes.

Kornacki: Once that happens, the trial can begin in the Senate. But while America waits, there's something that many of you, our Article II listeners, have been curious about.

Archival Recording: Hi, Steve.

Archival Recording: Hey, Steve.

Archival Recording: Hi from Bonn, Germany.

Archival Recording: Dallas, Texas.

Archival Recording: From Eureka, California.

Archival Recording: I'm wondering what role Chief Justice Roberts will play as the presiding judge, should there be an impeachment trial?

Archival Recording: How is Chief Justice Roberts likely to react?

Archival Recording: If the senators are the jurors and Chief Justice John Roberts gets to preside over the trial, why do they get to effect the process if they're just the jurors? And why doesn't John Roberts get to define what the process is?

Archival Recording: What kind of influence or constitutional weight will the chief justice have over McConnell and the rest of the Senate Republicans?

Archival Recording: Does he have any power over the outcome?

Kornacki: These are all great questions. The Supreme Court itself is defined by tradition, by power and by a bit of mystery, so naturally the court's role in a presidential impeachment trial is compelling. Today on Article II, what you need to know about the role of the chief justice in a Senate impeachment trial. (MUSIC) Pete Williams is the NBC News justice correspondent. He's helped us answer some listener questions in a past episode, but he's making his true, official debut as a guest here on Article II today. Pete, welcome to the show.

Pete Williams: My pleasure.

Kornacki: So let's start with the basics on this. The chief justice of the Supreme Court, the chief justice will have a role in the Senate impeachment trial. What is that role supposed to be?

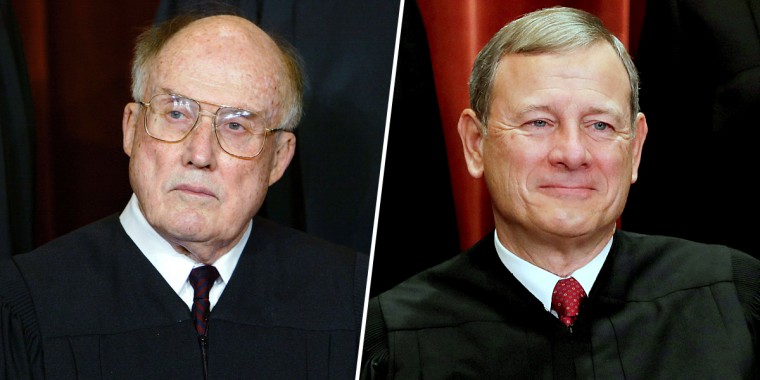

Williams: This podcast is Article II, and it's Article I of the Constitution that says when a president is put on trial for impeachment, the chief justice shall preside. So he has no choice. And John Roberts would be the third to have that responsibility. Salmon Chase did it in 1868 at the trial of Andrew Johnson, and William Rehnquist was chief justice in 1999 during the Bill Clinton impeachment trial.

Kornacki: So the term "presiding," is it understood what officially that means? The chief justice should be doing, shouldn't be doing? Are there official responsibilities, or is there some artist's license here?

Williams: (LAUGH) Well, he gets to sit up at the big desk in front of the room where the presiding officer of the Senate sits. He calls it to order. He says when it can adjourn. He calls for breaks. But I think the way to think of it is more like master of ceremonies than trial judge.

Kornacki: So you mentioned William Rehnquist presiding over the Clinton impeachment trial around this same time, 21 years ago. Were you around, covering that?

Williams: I was. I covered the whole run-up to the Clinton impeachment, the House proceedings, and then the trial in the Senate where he was acquitted.

Kornacki: So you remember this. What was the expectation about what Rehnquist was gonna do there?

Williams: Well, I think the expectation was not very clear, because it had been so long since we'd had an impeachment trial in the Senate, and a lot of things have changed since then, including television coverage. So that was one huge difference, (LAUGH) obviously. There wasn't much television coverage in 1868. He was a little bit more prepared for it than you might expect, because he had actually written a book about the impeachment of Andrew Johnson. So he just happened to have done a lot of homework on it.

William Rehnquist: Pursuant to the provisions of Senate Resolution 16, the managers for the House of Representatives have 24 hours to make presentation of their case. The Senate will now hear you. The presiding officer recognizes Mr. Manager Hyde to begin the presentation of the case for the House of Representatives.

Williams: Now at the end of the day, of course, it turned out he didn't really have to do very much, because the role is so limited.

Kornacki: You know, you hear about John Roberts, appointed by a Republican president, George W. Bush, and sometimes given the way politics works these days, you'll get, you know, some voices perhaps on the left saying, "Well, that would sort of color potentially how he would handle the role."

Rehnquist, back in '99, originally appointed to the bench by Richard Nixon, then by Reagan to be chief justice, so two Republican presidents kinda promoting him along; was there any concern about partisan loyalties or any of that affecting how he would handle it back then?

Williams: No, I don't think so. And you know, remember that first of all, no chief justice wants this (LAUGH) responsibility. They have it. They're stuck with it in the Constitution, but it's not anything they look forward to or relish. Well, let me put it this way: I think when it was all over, everybody thought that Rehnquist was very fair.

But part of that is because they just (LAUGH) don't have much responsibility over how things actually unfold, once the trial starts. The reason I say they're more like a master of ceremonies than a judge is this: in a trial, the jurors decide the facts and the judge decides the law.

So as the trial goes along, they have objections about whether evidence can be introduced, whether it's relevant, whether the question is bringing up hearsay and that kind of thing, and those are all decisions made by a judge. Now the rules say that the chief justice who's presiding can make those calls, but they also say that that can immediately be put to a vote by the Senate.

So if any senator doesn't like what the chief justice says, he can immediately refer it to the Senate for a vote or they can just vote on their own. There's no debate, the rules say. If somebody objects, there's an immediate vote. So he doesn't really have the final say, and they all know that. So for that reason, they don't sit there in an imperious way that judges often do in trials. They are well aware of their limitations.

Kornacki: That's interesting. So to make the analogy to the kind of trial we're all kind of familiar with, a traditional criminal trial, maybe something we see on Law & Order or something, this would be like if the judge in a traditional trial said, "Hey, that evidence can't be heard." The jury then voted, "We want to hear it," and then you'd have to have the evidence?

Williams: Exactly right. And in that sense, that brings up the only (LAUGH) real definitive thing I think that William Rehnquist did during the entire impeachment trial for Bill Clinton. There was an objection, because one of the House managers, that's what they call the prosecutors from the House who come over to present the case against the president, one of the House managers kept referring to senators as "jurors."

House Manager: We urge you, the distinguished jurors in this case, not to be fooled.

Williams: And there was an objection to that.

Archival Recording: Mr. Chief Justice, I object to the use and the continued use of the word "jurors" when referring to the Senate, sitting as triers, a trial on the impeachment of the President of the United States.

Williams: And Rehnquist ruled, "Yes, that's not exactly right. They're a lot more than jurors, so stop calling them 'jurors.'"

Rehnquist: The chair (?) is of the view that the Senator from Iowa's objection is well taken, that the Senate is not simply a jury; it is a court in this case. And therefore, counsel should refrain from referring to Senators as "jurors."

Archival Recording: I thank the court for its ruling.

Williams: That was (LAUGH) about the only definitive ruling he made during the entire trial.

Kornacki: One of the things I remember, I still see it come up now in descriptions of that time, he wore a special robe, Rehnquist did. He had gold--

Williams: Stripes.

Kornacki: Gold on the robe for the occasion.

Williams: Well, not for the occasion.

Kornacki: Oh, okay.

Williams: No, he had started doing that as chief justice. Rehnquist had his quirky side, and he was a huge fan of Gilbert and Sullivan. (MUSIC) And he had just seen one day the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta, Iolanthe.

Singer: The law is the true embodiment of everything that's excellent. It has no kind of fault or flaw and I, my lords, embody the law.

Williams: And there's a character in it who has a judicial function, who wears a robe with gold stripes. And he thought, "Boy, I sure like the look of (LAUGH) those, so he asked the Supreme Court seamstress to put gold stripes on his robe." And one day, he showed up in the Supreme Court, to the astonishment of all of us and (LAUGH) his fellow justices, that he had those gold stripes.

Chorus: A pleasant occupation for a rather susceptible chancellor.

Williams: So he had already been wearing those when he showed up in the Senate. But that was, as they say in the law, sui generis (UNINTEL) (LAUGH) unique only to him. John Roberts does not wear those stripes, so you won't be seeing them. They're not part of the normal chief justice's drag.

Kornacki: I'm glad I asked the question, 'cause I always thought that was something he had dusted off just for that--

Williams: No. (LAUGH)

Kornacki: --occasion. Did not realize that was a--

Williams: A special impeachment robe? No. (LAUGH)

Kornacki: You mention it too, that this is a responsibility perhaps a chief justice wouldn't want. I mean, was that the case with Rehnquist? Was this something that he felt was kind of forced upon him and a role he did not want to play?

Williams: Totally. This is a duty they undoubtedly don't want but can't avoid. And part of the problem is, you know, number one, it's sort of ceremonial. They're kind of a bump on a log. But secondly, they have a day job. And you know, this will happen, this Senate trial will happen likely while the Supreme Court is in a pretty busy time of the year, hearing cases.

And for that reason, by the way, the Senate rules say that the impeachment proceedings should begin each day at noon. Now that's the current rules, and that's to give the chief justice time to finish hearing the oral arguments, which start at 10:00 AM in the Supreme Court across the street.

And for those folks who don't know the geography, the Supreme Court is literally across (LAUGH) the street from the U.S. Capitol. So the chief bangs the gavel in the oral argument, ducks down into the parking garage of the Supreme Court, gets in a car, and zips across the street. You know, and the trial can go on all afternoon. So in the meantime, they're supposed to be hearing cases. They're supposed to be discussing cases with their colleagues at the Supreme Court. So you know, it's a real distraction from what he's normally supposed to be doing.

Kornacki: He has to take a car? He can't walk across the street?

Williams: He could, but for security reasons and to get him over there faster, they actually drive him over.

Kornacki: All right. I think that's a good...

Williams: Or at least that's what they did with Rehnquist. That's the precedent, and as you know, that's what the Supreme Court is all about.

Kornacki: Yeah, if somebody offered me a car to cross a street, I'd probably take it too. (LAUGH) I understand. We're gonna take a quick break here, Pete, but we'll be right back.

Kornacki: So we've been talkin' about the last impeachment trial in the Senate, the role of the chief justice back then, William Rehnquist. Let's get to the present tense right now. If there is a Senate trial for the impeachment of Donald Trump, it'll be John Roberts, current chief justice, who presides over that. Roberts has been on the court really 15 years now. It doesn't seem like (LAUGH) it's been that long, but it's been 15 years, and he actually succeeded Rehnquist as the chief justice, when he passed away?

Williams: Yes, and he was one of Rehnquist's clerks, so that doesn't often happen that a former clerk replaces the justice for whom he once clerked, but that's what happened there.

Kornacki: What is Roberts' reputation that he would carry into a Senate trial?

Williams: Well, remember at his confirmation hearing, he said it was the job of justices and judges to call the balls and strikes, but not to decide who pitches and who bats.

John Roberts: And I will decide every case based on the record according to the rule of law, without fear or favor, to the best of my ability. And I will remember that it's my job to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.

Williams: You know, that's the reputation he's tried to have as one of judicial modesty, and there have been a lot of people who say he hasn't stuck with that. Critics, especially conservatives, were critical of his ruling that rescued Obamacare. But for the most part, he has moved the Supreme Court in an incremental way toward a more conservative direction, but he's not somebody who seeks the limelight.

Kornacki: There's been some suggestions that the reputation of the court, the kind of standing of the Supreme Court in American life weighs on John Roberts a little bit. You go back 20 years, the Bush/Gore decision that kind of settled the 2000 election; the sort of politicization of the Supreme Court, it becomes an issue in presidential elections.

You know, we hear about Donald Trump appealing to the conservative base by promising, "Hey, somebody from this list will go on the Supreme Court." The idea, you know, that a lot of folks look at the court now as there are Democratic justices and Republican justices.

Williams: Yeah, he hates that. He hates that.

Kornacki: Yeah, is that true that that does weigh on him? And does that affect how he would handle something like this?

Williams: Well, yes and no. I mean, I'm sure he goes in there, not intending to be anybody's servant. I mean, he's not going in there to push the proceedings in either a Republican or Democratic direction. He's certainly not gonna be the Republicans' judge. But the other thing is even if he wanted to be, he couldn't. He doesn't have that much power. That's the other part of it. The Senate really has all the control over this.

Kornacki: You know, Mitch McConnell, the Majority leader, he's talked a little bit about his expectations for how a trial would go, including last month how he thought Roberts would handle this.

Mitch McConnell: The way this will work is I would anticipate the Chief Justice would not actually make any rulings. He would simply submit motions to the body, and we would vote.

Kornacki: Was McConnell trying to deliver any message there?

Williams: (LAUGH) Well, I don't know whether McConnell was trying to tell the chief, you know, "Just lie back and let us run the thing," but in fact that's really how it works. Now I don't think he's gonna dodge every single question and leave it to the Senate.

I think he will have to make some rulings. There'll be some procedural rulings. And by the way, a lot is gonna depend on whether the Senate calls live witnesses. They did not do that in the Clinton impeachment. They had witnesses that were interviewed before the trial. When the House managers presented their case, they brought monitors on to the Senate floor and played little videotape excerpts.

If they have live witnesses on the floor of the Senate, I can't imagine they're gonna do that, they seem not to want to, but if they did, then I think there would be a lot more call for the chief to rule on whether certain statements are admissible or not.

Kornacki: If it were to come to John Bolton or some other live witness testifying in a Senate trial, obviously that would be a difference from what you got in the Clinton trial in 1999. What are the variables that Roberts, that John Roberts presiding over this would then face that Rehnquist didn't have to face back in '99?

Williams: Well, it's just like in a normal trial, where a lawyer asks a question and counsel on the other side says, "Objection." It's irrelevant, it's immaterial, it calls for speculation, it's hearsay, or whatever, and then Roberts is gonna have to make rulings.

Now the federal rules of evidence don't directly apply in a Senate impeachment trial. And the rules don't really say much about relevance. It just says that the presiding officer gets to decide whether-- let's see, I'm looking at the rules right now. "He may rule on all questions of evidence, including but not limited to questions of relevancy, materiality, and redundancy of evidence, and incidental questions, which shall stand as the judgment of the Senate, unless," (LAUGH) it says, "some member of the Senate shall ask that a formal vote be taken." So in theory, he has the authority to rule on these objections, but in fact, the Senate has the ultimately say. So if they want an answer, they're gonna hear it.

Kornacki: So again, it's that prospect of the jury overriding the judge?

Williams: (LAUGH) Exactly.

Kornacki: Right. You don't see that one on Law & Order.

Williams: No.

Kornacki: So yeah, last question. I mean, again, this idea that this would be the third impeachment trial in history; folks looking back 20, 30, 50 years from now, maybe longer, would always see John Roberts' name as part of this process, if there's a Senate trial. But it sounds like the way you describe it, he doesn't want that?

Williams: Well, he doesn't want it. And in fact, just as Salmon Chase and William Rehnquist before, they'll be footnotes in the history of these impeachment trials, because their role is really, as I say, largely ceremonial. In theory, they've got a lot of power. In fact, they don't.

Kornacki: All right. NBC justice correspondent Pete Williams. Pete, really appreciate you doin' this. Thank you.

Williams: My pleasure.

Kornacki: Article II: Inside Impeachment is produced by Isabel Angel, Max Jacobs, Claire Tighe, Aaron Dalton, Preeti Varathan, Allison Bailey, Adam Noboa, and Barbara Raab. Our executive producer is Ellen Frankman. Steve Lickteig is the executive producer of audio. I'm Steve Kornacki. We'll be back on Monday.

Archival Recording: Thanks.

Archival Recording: Thanks.

Archival Recording: Thanks.

Archival Recording: Auf wiedersehen from Germany.

Archival Recording: Bye-bye.