WASHINGTON — Democrats are hopeful about retaking the House next month, but to do that they are going to have to overcome an inherent disadvantage in many states due to gerrymandering.

Every 10 years, the states redraw the lines of their congressional districts to reflect population changes in the previous decade. In most states, the party in power controls how the lines are drawn and after a Republican wave election in 2010, the GOP drew some very favorable and, in some cases, very odd-looking maps.

Those maps remain a major hurdle for Democrats in 2018, a storm surge wall against a potential blue wave, and looking previous election data you can see their impact.

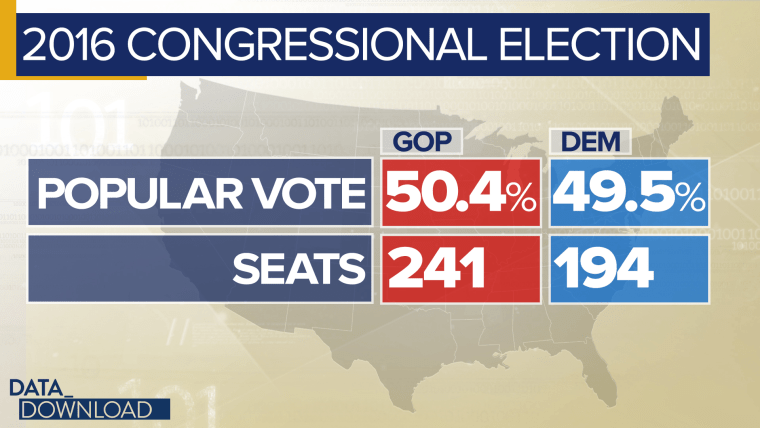

The national numbers tell some of the story.

In 2016, Republicans captured 50.4 percent of the national two-party House vote, while Democrats captured 49.5 percent. That’s a difference of one percentage point. But when all the votes were tallied by district, the GOP won 55 percent of all the House races, 241 seats, while the Democrats held 45 percent, 194 seats. That’s a 10-point split.

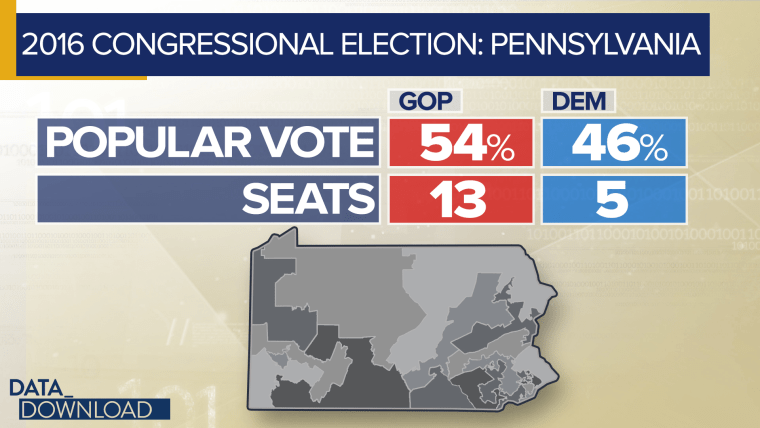

A better way to see the impact of gerrymandering, however, is at the state level. And Pennsylvania, which recently had its congressional map voided and redrawn for 2018 offers a clear view.

In the 2016 election, the two-party U.S. House vote in the state gave a good advantage to the Republicans. The GOP won 54 percent of the vote, while Democrats captured the other 46 percent.

But at the district level But Republicans did much better. With that 54 percent of the vote; they won 72 percent of the state’s 18 House seats — 13 of them. That’s a pretty big gap between the percentage of the vote won and the percentage of seats won, but at least the same party won the majority of the popular vote and districts.

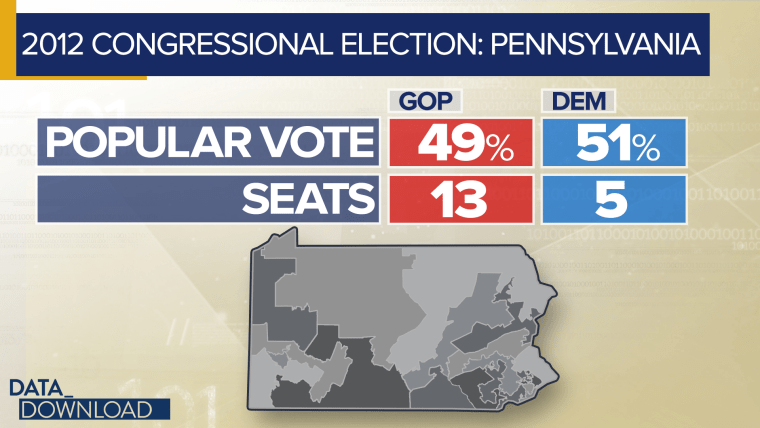

Flashback to 2012, however, and you see just how big a role that Pennsylvania map has played in the GOP’s control of the congressional delegation.

In 2012, President Barack Obama carried Pennsylvania on his way to re-election and the Democrats won the two-party House vote in the state by about two points, 51 percent to 49 percent.

What did the partisan split look like in the Pennsylvania House delegation after that election? It was exactly the same, 72 percent for Republicans — 13 seats — and 28 percent for the Democrats — five seats. In fact, there was no movement at all, the same party held every seat after 2012 as they did after 2016.

That stability gets to how gerrymandering can work. You can create safe seats for either party by “packing” like-minded voters together or by “cracking” a group apart and spreading it across several districts. In Pennsylvania, the map shows a bit of both approaches.

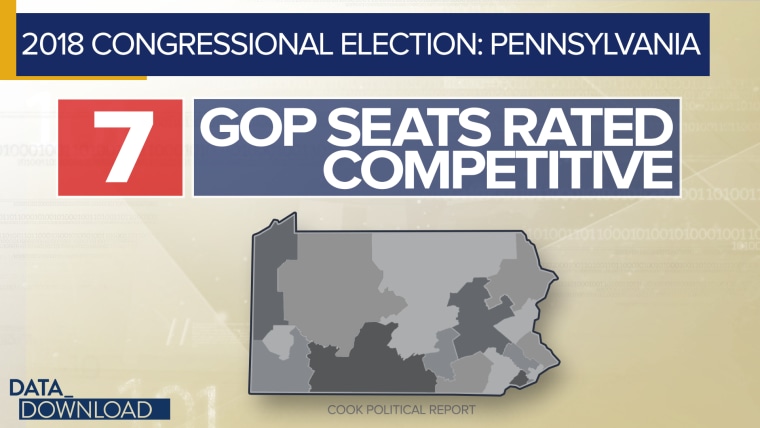

But that old 13-to-5 Pennsylvania map was thrown out by the state’s high court this year and a new map was drawn with lines that, on the surface, look a lot more sensible. We’ll find what those new districts do to the partisan composition of the state’s delegation next month, but some analyses project a big change.

The Cook Political Report currently rates seven GOP-held seats in Pennsylvania as competitive. And it rates four of those seats as “leaning” or “likely” Democratic. It also projects one seat held by the Democrats will likely end up in Republican hands.

If those seats actually flip in November, the delegation will look a lot more like the state’s 2016 and 2012 total House votes. It will look more like the delegation of a 50/50 political state.

That would help the Democrats in their goal of flipping at least 23 seats nationally to recapture the House, but there are other challenges out there.

For one Pennsylvania’s not alone. North Carolina’s congressional map was just thrown out over the summer for being too partisan, but will still be used for next month’s election. Ohio has some strange-looking districts, as do Texas, Louisiana and Kentucky.

And, to be fair, Democrats’ living patterns make it easier for the GOP to gerrymander them. Democratic voters tend to cluster in urban areas around major cities, making them easier to pack into a few districts.

Is there a solution for the Democrats? Well, gerrymandering is not a Republicans-only activity. Democrats play the game, too. There will be legislative and gubernatorial elections across the country in November and, in most states, those governmental bodies will draw or help draw the next set of district lines.

In other words, Washington may be watching the fight for the House and Senate on election night. But keep an eye on the battles in state capitals around the country. Those races may have more meaning for what the House looks like in the next decade.